Inspiration-Letters 17

I have always loved the Buddha. The fact that he was the son of the king, and the crowned prince, and the fact that he renounced all the privileges and pleasures attendant on that title, to look for God, has to be one of the greatest spiritual romances of all time. I especially like the vow he took at the foot of the Bodhi tree, that he would neither eat, nor drink, nor move from that spot, until he had achieved his goal, full God-Realisation, Enlightenment.

I have always loved the Buddha. The fact that he was the son of the king, and the crowned prince, and the fact that he renounced all the privileges and pleasures attendant on that title, to look for God, has to be one of the greatest spiritual romances of all time. I especially like the vow he took at the foot of the Bodhi tree, that he would neither eat, nor drink, nor move from that spot, until he had achieved his goal, full God-Realisation, Enlightenment.

When the Buddha gave up all his clothes, money, gold, and family to find the Truth, that was his renunciation. When the Buddha, fired with unearthly determination for God, vowed not to move from the sacred tree until he had reached his Goal,that was his devotion. Renunciation and devotion go together.

I take devotion as one of the divine emotions. In other words, it is something we cannot feel when we are fully preoccupied with the outer world and all of its dazzling pleasures and meaningless woes. It is only when we can clear the mind and listen to the heart, the inner self, that devotion can come forward.

Devotion, devotion, devotion.

When I say this word, I realize it is like a mantra. A mantra is a word whose very sound evokes or invokes the quality of that particular word.

Devotion rhymes with "ocean" which is just a coincidence, but it's true that devotion is a key that we can use to discover our vastest, cosmic Self. When we devote ourselves to God, we swim in his consciousness, we fly in his heart, and we find at the end of our journey that our hearts and God's Heart are one and the same.

I like the scene in Drink, Drink My Mother’s Nectar, Sri Chinmoy’s wonderful play about the life of the great Sri Ramakrishna, in which the Master gives one of his final talks to his beloved disciples:

RAMAKRISHNA: In this body two persons live: God in the form of an Avatar, and God in the form of a devotee. An Avatar’s devotees come with him and go away with him.

RAKHAL: So you must not go away alone, leaving us behind.

RAMAKRISHNA: The religious mendicants appear quite unexpectedly out of the blue. They sing and dance, and again they disappear quite unexpectedly. Hardly anyone recognizes their aspiration. Similarly, great spiritual Masters appear and disappear without being recognized. (Ramakrishna closes his eyes for a minute.) I tell you all that a life without renunciation is no life at all. Renounce your ignorance. Renounce your knowledge. Renounce what you have and what you are.

I really like Sri Ramakrishna’s image of the spiritual beggars, sadhus, appearing out of nowhere, singing and dancing, and then once again vanishing into nowhere. God certainly does inspire us and guide us in mysterious ways! Who would have thought that Sri Chinmoy, a spiritual Master, poet and musician from the easternmost reaches of India, would touch and inspire so many lives in such a profound way?

Devotion is so valuable because it purifies us, simplifies our lives and clarifies our minds. Through devotion we become as clear and as flexible as water, able to absorb and to reflect the effulgent light and joy from God's Heart.

If you feel called to the life of the spirit, the life of renunciation and devotion, remember that there is no better time than right now to base your life on God and spirituality, and to find true and abiding meaning and purpose. The Sunlit Path is for all.

“The devotion-musician in meMahiruha Klein

Is all ready to play

God's Song of Love

Upon my heart-strings

In the New Millennium.”

— Sri Chinmoy, from The New Millennium

Editor

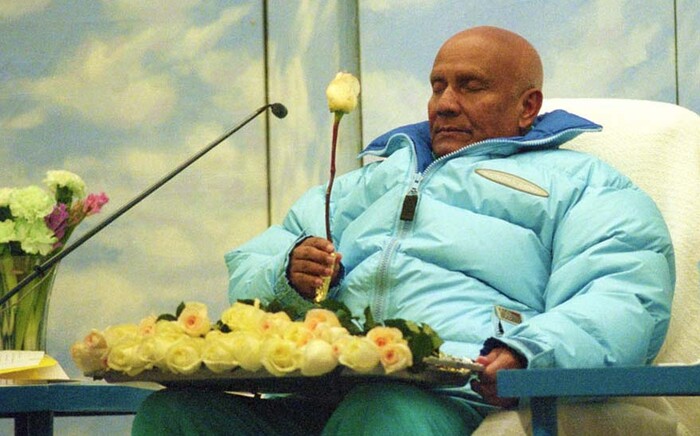

Title photograph: Pavitrata Taylor at Sri Chinmoy Centre Gallery

All Pink in Tenerife

The skeins of devotion run through our lives from a very early age. As a child I was devoted to my coin collection, those stolen pennies intended for the Sunday church appeal but instead placed under the wheels of the passing train that ran adjacent to our home. Crushed beneath the roaring thunder of the 10am Sunday goods express into pliant bronze wafers, they were squirreled away beneath my bed, my hoard of secret treasure. I was devoted to our passing parade of pet dogs too, terriers, collies, strays that shared our lives for a while. Then devoted to my first gun, polishing the sleek, murderous barrel and lining up the neighbor’s hens in mock assassinations.

The skeins of devotion run through our lives from a very early age. As a child I was devoted to my coin collection, those stolen pennies intended for the Sunday church appeal but instead placed under the wheels of the passing train that ran adjacent to our home. Crushed beneath the roaring thunder of the 10am Sunday goods express into pliant bronze wafers, they were squirreled away beneath my bed, my hoard of secret treasure. I was devoted to our passing parade of pet dogs too, terriers, collies, strays that shared our lives for a while. Then devoted to my first gun, polishing the sleek, murderous barrel and lining up the neighbor’s hens in mock assassinations.

Other objects awoke a touch of reverence too, a balsa wood plane kit, a bear’s tooth from someone’s Alaskan adventures, rough and wild stones from romantic places – obsidian from volcanic mountains, green jade streaked with lightning veins of quartz and hard-won from alpine streams, nuggets of gleaming pyrites - and the thigh bone of an extinct moa, an uncle’s whispered gift. I brooded over the great shank of yellowing bone, imagining the four metre high bird stalking through primeval swamps until a relative confessed it to be the remnant of a recently deceased cow. And in my feeling for my parents, that mixture of love, exasperation, remorse, there might also have been the stirrings of devoutness, hints of other loyalties and loves to come.

These were the precursors of the deeper and truer devotions of which we can be capable. And where childhood and all those childhood things have gone, those tiny currents of reverence and veneration have survived, blossomed in a discipleship that has raised up and recognizes devotion as the highest of achievements.

“God gives us a bridge,” writes Sri Chinmoy in Rainbow-Flowers,” and the name of that bridge is devotion. Both the seeker in us and God frequently cross this bridge. God comes to us to take care of our aspiration. We go to God for peace, light and bliss. Devotion is the bridge between our receptivity and God's Divinity.”

This devotion gives us fearlessness, frees us from all worldly anxieties, connects us to our highest and truest selves, imparts God-reliance and unwavering faith. And Sri Chinmoy would tell us that it is this fire of devotion that will burn up all our worldly attachments and is itself the magnet that most powerfully draws the grace of God. In Sri Chinmoy Answers ( Part 32) he writes of his own childhood tutelage in devotion:“In India we have our tulsi leaf. The spiritual significance of that leaf is devotion. One of my Indian 'mothers' used to worry that I did not have any devotion. Her name was Mridu-di. Every day she used to run after me only to place that leaf inside my mouth”.

By chance I came across a photo this morning from a years ago Christmas trip to Tenerife. Like Milarepa’s guru Marpa Lotsawa – who famously trained Milarepa in devotion, egolessness, surrender by having him build, then pull down, then rebuild and again pull down, three times, a stone tower – our guru in Tenerife had a group of us build a 100 meter running track on the volcanic rubble of an empty allotment near our hotel. Each morning Guru would visit and request further challenging modifications – the hot, perspiring days trickled by while we labored at our sadhana, leveling, shoveling, crushing scoria and cinder into a perfect and level smoothness, even finding carloads of illicit bouganvillea to line the track with ardent purple flowers. Seeking through our work the extinction of the little ‘I’ and the achievement of a surrendered devotion. Like Marpa, our Guru was drilling us in the great enlightenment game, rarely ever using the finally completed track.

Oddly, in the photo that reminds me of all this, I am dressed in pink and I remember now that early in this vacation I had one day thrown all of my mainly white clothing into a laundry tub along with a vermilion-red ‘color fast’ jersey. The inevitable happened of course and for the next two weeks I wandered the island of Tenerife in varying shades of salmon, rose, hot pink, cherry blossom pink - and the subject of much good-natured ribbing. Performing on stage in our evening singing I was an alien figure in my deviant, pale pinks, and felt myself suffused in a strange glow, the mis-laundered, adulterated whites radiating a strange effulgence that might have been mistaken for some sign of auric saintliness. But was instead a domestic gaffe.

Guru’s resculpting of the obdurate stuff of our humanity was also much in evidence in the highlight years of his running. Especially in the ‘road crew’ years. He would often go out late at night – right through the winters and usually in the post midnight wee hours – and jog along one of his many favorite, often very long courses. He would alert his chosen road crew boys to accompany him, and these individuals would go ahead in the darkness to clear the pavements of fallen debris, repaint direction and distance markers and ensure that everything was satisfactory. This was one of the most grueling tests of our warrior spirit and my own several outings I still remember for their biting cold, the inner struggle to remain cheerful, and waves of tiredness. How intense discipleship can be when a Master and the relentless force of his love push you beyond your limits, free you from the imprisoning constraints of ordinariness.

How curious we are, trudging through the mire of our karmic reapings; the meteorite showers of desires, anxieties, loneliness; our private gallimaufry of personal failings; the tug of unlived lives…..yet looking always upwards to the stars and longing for liberation, redeemed by our bursts of piety and devotion, capable sometimes of great nobilities of thought and lofty acts of charity. And attracting the compassion of God and the alchemizing grace of the Guru, the one who undertakes the great task of transforming our base nature into a dazzling divinity.

‘Dazzling’ here reminds me finally of my childhood piano teacher. When she wasn’t beating my digits with her bamboo cane at each fumbling and infraction, she would sometimes display a quite dazzling divinity of her own and soar far above her usual sultry moods, shunt me along to the edge of the piano stool and launch into a rhapsodic magnum opus to inspire me and fill me with ambition. The piano transformed her and I in turn was transfixed. Like a sudden shaft of sunlight in a stormy, dark sky her sweeping arpeggios and rampaging chords swept us away, age and enmity forgotten, and waves of a strange, existential gladness filled my heart. Gillian became lost – though more truly found – in these outpourings and ushered us both to a different and higher world. She was expressing her devotion for life and the unconscious yearnings of her soul, for as Sri Chinmoy wrote: “ Art, like love, is a force of oneness with the infinite. When we create a piece of art, we are really re-creating or reflecting some beauty of the Infinite."

Guru’s words should end my ramblings and summarize all we need to know. In Service-Boat and Love-Boatman he reminds us: “In the spiritual life, if one wants to make quick progress, then I wish to say that devotion is the only answer. If there is devotion in the entire being, then one can drink nectar every day in one’s spiritual awakening, spiritual discipline and spiritual realization. It is devotion that gives us sweetness in our life, and carries us to the Source of life-immortalizing nectar.”

Jogyata Dallas

Auckland, New Zealand

On Worship

“The opiate of the people” was Karl Marx’ opinion of religion. The father of communism saw religion as an illusory veil, an escape from reality leading to a hollow promise of happiness. Yet no matter how hard later regimes founded on his ideology have tried to purge this so-called illusion from man’s life, they may have succeeded in destroying its outward forms, its temples and churches, but not the seed they sprouted from.

For this seed is man’s spiritual hunger, as innate in him as breath and heartbeat. And the flower that grows from it is called devotion. Devotion inspired the Sufi dervishes to don their white robes and whirl their bodies round and round in adoration of God. Devotion urges the Christian on his knees and makes him fold his hands in prayer. It speaks to the prayerful Muslim who rolls out his carpet five times a day facing Mecca, to the devout Buddhist sitting cross-legged in meditation and to the pious Hindu offering flowers and incense at his temple’s shrine. The need to worship is part of man’s inner constitution. Even though it may lie dormant from time to time, hidden by mountains of doubt, ambition or a plethora of worldly temptations, its rays are bound to penetrate even the thickest clouds eventually.

The birth of science some two centuries ago ushered in a paradigm of life that could uphold itself and even thrive without the need for a higher power or supreme Being to justify its existence. Yet the current trend in the world sees large groups of people returning to spiritual values. The same seed of devotion and spiritual hunger fuels this silent counter-revolution.

Worship implies the recognition of something greater or higher than ourselves. Each time we recognize and admire greater wisdom, capacity or power we perform an act of worship. The football fan that has decorated his bedroom walls with pictures of his ball handling idols performs worship. As does the teenage girl screaming behind the crush barrier as the band members are hurried to the tour bus. Movie theatres have become modern-day temples with actors for deities. But in this form of worship the insurmountable barrier of status, caste and fame prevents any real communication between the adored and his devotee. Even if they were to meet in real life they could never truly reach each other. For the sheer admiration and adoration felt by the latter prevents the former from establishing a feeling of oneness, necessary to share their common humanity. “Fame always brings loneliness,” as one writer once aptly stated. And usually the former is quite full enough of himself already to aspire to any sort of common ground, what with ego and vanity.

Then there is the question of material objects. Men, for instance, can show the purest devotion to their cars, worshipping them with an almost religious zeal. The Saturday morning wash has become a common ritual in many a middle-class suburb. It is said that God can be found everywhere, so why not in an automobile? However, the reason for the car owner’s lavish attention has often little to do with finding God and everything with personal status. No matter how much divinity a BMW may have, it is usually purchased to exhibit affluence, not spiritual aspiration.

So ultimately the earthly forms of worship fall short of the mark. They cannot lift man to that greater or higher existence he is secretly and often unconsciously looking for. It is only in the spiritual life that worship serves its true purpose. For in its purest form worship is our innate love of God. Worship is our communion with God. And although God unquestionably has more wisdom, capacity and power than we have, it is never beneath His dignity to share it with us. In spiritual devotion there is always a feeling of oneness between the devotee and his Lord, and in this feeling of oneness real satisfaction abides. Sri Chinmoy explains, “A child does not care to know what his mother is. He just wants his mother’s constant presence of love before him. Similar is the devotee’s feeling for his Lord.”

When one is lucky enough to have a spiritual preceptor, an illumined soul to help him on his life’s journey, devotion often takes the form of love for one’s teacher. Yet Sri Chinmoy often emphasized that the love and devotion of his disciples was not meant for him, but for the Supreme in him, the divinity inside him that he had become fully aware of.

When we meditate with an illumined teacher the pure feeling of devotion – that fruitful inner seed in us – comes to the fore naturally and spontaneously. It was always there, but the teacher draws it out, just like a bee-keeper draws out honey from a beehive. Just like the bee-keeper has to be careful not to get stung by the bees, the spiritual master also risks being stung by our doubts, jealousies and insecurities. But he does his work unperturbed, for in him God’s unconditional Compassion operates.

Before devotion comes, the seeker often has a feeling of awe for his teacher. He admires his teacher, but he does not dare to claim him as his very own. His feelings of awe and reverence actually form a wall that stands between him and his teacher, preventing genuine oneness. It is just like the movie star that is placed by his fans on an unreachable plateau. Devotion demolishes this inner wall. It immediately brings the sweetest feeling of oneness, because it is based on the heart’s love instead of the mind’s reverence.

Hence, when worship is merely founded on admiration it increases the distance between the devotee and the adored. When it is fuelled with true devotion it strengthens their inner bond and ultimately makes them inseparably one.

Abhinabha Tangerman

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

On The Sunlit Path

by Suchana Cao

Once upon a time there was a little girl who used to have sweet dreams about living in a more peaceful world. Her relationship with the Lord was sincere and close but as time went on her heart would sometimes cry asking God the whys of her separation from Him. It happened one day — when she was already a teenager, at a family gathering — that an older friend said to her, “a most luminous being is coming to you, He will be a Divine Gift in your life, He is coming from a faraway land but I don´t know who He is.”

A gap of about thirteen years would pass by until she was invited to join the Sunlit Path, which she did enthusiastically. What would it happen from that day on? Life has not been empty of outer obstacles and some inner parts of her being would revolt to accept the inner voice as well, however, a most powerful magnet of unconditional Love-Light would guide her to fulfill her soul’s dream — working for a divine cause.

To tell you the truth, dear reader, this is not anyone else’s story but my own experience of “a dream which becomes true”! As soon as I started meditating under the compassionate inner guidance of Guruji Sri Chinmoy, I felt within that my obedient attitude would be a must in achieving some kind of inner progress in this lifetime. Because dreams are in their own world, it was so up to me to bring them down little by little for my own sake with my Guru´s help.

Sri Chinmoy often refers to ‘love, devotion and surrender’ as the three main significant steps to follow on his path. He also teaches that the inner sun — our soul — is million times brighter than the outer sun, our golden star. In his magnificent recipe of inner and outer progress, I have also found as a seeker that the self-giving aspect is the key of this Sunlit Path. Moreover, the last twenty-seven years had led me to discover that a moment of ´gratitude´ is not only an important ingredient but also the filling and dressing in my inner life. And so the food for the soul is served.

In the meantime my mind, vital and body accepted to inspire each other and by Grace, all Grace from Above, they started to do better with an iota of silent self-transcendence-work. In this way new dreams have surpassed the old ones, frustration has become joy, anxieties turned to harmonious days and fear was overcome.

Each time I try to elevate my consciousness or make the flow of my meditation expanded with oneness, I remember my Spiritual Master Sri Chinmoy lovingly and unconditionally and soulfully praying, meditating, chanting, painting, singing, joking, sporting and especially smiling. From his eternal Abode upon his manifested Sunlit Path, his unique path of the heart, He is once more blessing me to go on –his hands and eyes- as the most luminous being!!

Suchana Cao

Argentina

Devotion to the Feet of God

“My eyes adore

God's Feet.

My heart kisses

God's Footprints.”

—Sri Chinmoy, from Two God-Amusement-Rivals: My Heart-Song-Beauty And My Life-Dance-Fragrance, Part 1, 1996

Spiritual importance, symbolism and imagery centered on the feet of God and other holy beings can be found across religions and cultures. Whether Buddhist, Christian or Hindu, a theme can be traced wherein a seeker invokes the notion of placing him or herself at the feet of a personal God and/or holy being in order to receive protection, illumination, forgiveness and communion with the divine.

There is a rich tradition within various branches of Hinduism of worshipping the “lotus feet” of God and of prostrating at the feet of Gurus and other holy saints. In the Ramayana epic, when Rama and Lakshmana are in exile from the palace, Rama’s half-brother Bharata takes sandals back to the palace after asking Rama to step in and out of them. He places these sandals on the throne and worships them while Bharata serves as regent.

Sandals are again revered in a Tamil literary work of one thousand verses praising the sandals of Lord Ranganatha, the reclining form of Lord Vishnu. Written in 1313 by a Vedantic scholar named Vedanta Desika, it is called Paduka-Sahasram and is considered a pinnacle work of devotional poetry.

In Asian countries where Buddhism flourishes, one finds “Buddhapada” – Sanskrit for the footprints of the Buddha. Buddhists believe that after Lord Buddha achieved enlightenment, he took steps that left an imprint of his feet in actual rocks in order to leave a reminder of his presence on Earth. Buddhapada stone carvings and relics can be found across Asia - especially in Thailand, Japan and Sri Lanka. Typically the artistic renderings of the footprints of the Buddha have spiritual symbols on the feet and toes such as the Dharma Wheel, the lotus or the swastika.

Despite the emphasis on God without form within Islam, sacred footprints in stone are part of Islam’s heritage as well. The Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia - The House of Allah - is the most sacred spot on Earth for Muslims. Around the world, Muslims face the Kaaba during their daily prayers and it is a place for pilgrimage that each Muslim is supposed to visit at least once in his or her life. Inside the Kaaba, there is a small building which contains a stone with footprints imprinted on it. Muslims believe the footprints on the stone are those of the Prophet Abraham from the time when he was building the Kaaba. When Muslims pray towards the Kaaba five times per day, they must wash their own feet up to the ankle before performing their prayers.

Growing up in the Baptist tradition, I remember the stories of Mary Magdalene washing the feet of Jesus (Luke 7: 36-50) (The New English Bible, 1972) as well as the moment when Jesus washed the feet of the disciples at the Last Supper (John 13:3-17) (The New English Bible, 1972). Philip Bennett Power served as a minister in the Church of England in the mid-1800’s and wrote a number of religious books for children and adults. In his book The Feet of Jesus in Life, Death, Resurrection and Glory, Power explores all the passages in the Bible with content related to the feet of Jesus - whether the scenes involved angels, the disciples or people who experienced healing when they fell at his feet in prayer and longing. Written in a devotional style, Power describes divine light inherent in the symbolic feet of Jesus in the following passage:

“But what could not be revealed on earth, is revealed in heaven - we are allowed to see what the feet and path of Jesus really are. In all Christ's comings to us now, in all His ways with us, in all His leadings into duties, He comes with feet all light and bright.

The duties and dispensations may seem dark, but if He be with us His, feet will bring light into them. The light will come in its own time. Jesus does not change dispensations -sorrow remains sorrow; but He comes with his own light into them, and then the sorrow remains a sorrow, and yet is turned into joy. Let us believe, then, in Christ's ability to bring light into all darkness. Let us seek to see the feet and all will be well; let our anxiety be, not lest we should fall into any trouble; but lest if we do, Jesus should not be in it.”

— Philip Bennett Power, from The Feet of Jesus in Life, Death, Resurrection and Glory, 1872

An interesting convergence of the imagery of the divine and the footprint across religions can be found in the lore about a mountain in Sri Lanka called Sri Pada by the Buddhists and Adam’s Peak by Westerners. A conical shaped mountain rising 7,359 ft. (2.243 m.) into the sky with no other mountains nearby, Sri Pada is the holiest mountain in the world for Buddhists. They believe that a rock formation on the top of the mountain is the left footprint of the Buddha - created as he strode across the Heavens with his right footprint from the stride coming down in Thailand. Hindus believe it is the footprint of Lord Shiva, Christians attribute it to St. Thomas and Muslims to the Prophet Adam as he left the Garden of Eden. A shrine is located at the top of the mountain and the mountain is a major pilgrimage site for Buddhists and Hindus, especially during the peak season of December to May when as many as 100,000 people might make the climb on a weekend. Climbers can wait in one spot for hours as they attempt to reach the top of the mountain.

To seek deeper understanding for the prevalence of spiritual imagery related to the feet, the writings of contemporary Spiritual Teacher Sri Chinmoy provide clues into the attraction of this symbol for a spiritual aspirant. In advice for his students’ meditation practice, he states:

“When the beginner meditates early in the morning, he should meditate on the Feet of the personal Supreme. Then, along with his own devoted love, he will feel God’s Compassion and Concern. He will say, “Here is someone who is really great, infinitely greater than I. That is why I am touching His Feet with such devotion.” He will feel that there is some purpose behind what he is doing. By touching the Feet of the Supreme, he is trying to become one with the Supreme. He feels that for him this is the easiest approach. If someone is very tall, I won’t be able to touch his head. But I can touch his feet. Whether I touch his feet or his head, I can say that I have touched him. But when I touch his feet, immediately I get the feeling of purest joy and devotion.”

—Sri Chinmoy, from The Vision of God’s Dawn, 1974

Sri Chinmoy posits three main precepts in his spiritual path – love, devotion and surrender. By centering this divine love, devotion and unity with God’s Will on the image of God’s Feet, the seeker can more quickly tune into the inner sentiments that foster union with the highest. He describes,

“The first step in our journey is love, the second step is devotion and the third step is surrender. First we have to love God. Then we have to devote ourselves to Him alone and finally we have to be at His Feet and fulfil ourselves.”

—Sri Chinmoy, from Service-Boat And Love-Boatman, Part 2, 1974

The concepts of God’s Feet and devotion are often found together in Sri Chinmoy’s spiritual philosophy. He writes,

“Devotion not only arrives

At God's Door

But also goes inside

And sits at God's Feet.”

—Sri Chinmoy, from Seventy-Seven Thousand Service-Trees, pt. 20, 2001

In an interview concerning his artwork, Sri Chinmoy discusses how meaningful God’s Feet and devotion are to him:

“...God asked me where I want to be. He said, "Do you want to look at My Eyes or at My Feet?" I said, "I get more joy by looking at Your Feet than by looking at Your Eyes." In the Mahabharata, our Indian epic, the Kauravas wanted to be by the head of Krishna, but the Pandavas wanted to be at the feet of Krishna. In my case, I get infinitely more joy by being at God's Feet. I prefer the devotional aspect of life. The other day I was reading the Puranas, which is one of India's sacred books. There Krishna was saying, "I am ready to give you liberation because it is easier to give you liberation than to give you devotion." In liberation, the seeker goes his own way; the bird flies away. But if there is devotion, then there is a magnetic pull between the Master and disciple-the sweetest feeling-and the Master plays with the disciple-bird in the sweetest way. So I feel that the sweetness of devotion far surpasses the grandeur of liberation.”

—Sri Chinmoy, from Sri Chinmoy Answers, Part 3, 1995)

Sri Chinmoy’s emphasis on this devotional bhakti form of yoga carries on a centuries old tradition within Hinduism of taking refuge, finding forgiveness and purification at the feet of God. Francis Xavier Clooney, the author of Hindu God, Christian God : How Reason Helps Break Down the Boundaries between Religions, states that the word feet can be found 258 times in a classic Tamil sacred text called the Tiruvaymoli (a poem of 1,100 verses written by Nammalvar in the 9th century).

Similarly, Sri Chinmoy’s final volume in a poetry series called Seventy-Seven Thousand Service-Trees contains no less than 30 poems including the imagery of God’s Feet. The final poem composed in the 50th volume – the last of these poems composed during his lifetime – is itself concerning God’s Feet. The poem follows:

“My heart’s gratitude-tears

Every day I place

At the Feet of my Lord Supreme.”

— Sri Chinmoy, Poem no. 50,000, from Seventy-Seven Thousand Service-Trees, pt. 50, 2009

Ancient and contemporary spiritual writers alike fix their focus devotedly on the Feet of God. Different religious scriptures contain rich symbolism and imagery of God’s Feet. To intensify a supplicant’s yearning and closeness with the Highest, contemplation of God’s Feet beckons as a path to reach deeper spiritual wisdom. With this perspective foremost in one’s awareness, the advice found in this poem by Sri Chinmoy sums it up in perfect simplicity:

“Start watching God’s Feet

With utmost devotion

And never stop.”

—Sri Chinmoy, from Seventy-Seven Thousand Service-Trees, pt. 26, 2009

Sharani Robins

Rhode Island, USA

Taking Shortcuts

by Tom McGuire

I like taking shortcuts. Why follow a zig zag path when you can take the simplest, straightforward route? If your goal is the pinnacle of enlightenment, then the difference between them could be measured in lifetimes.

There is a term used in spiritual circles, the ‘sunlit path’. The very phrase invokes a sense of the way forward being illuminated by a light from above; a way bright and promising; a road fast and sure.

Many books have been written on the passage to enlightenment and realisation, but teachers of the sunlit path tend to say that our heart’s inner cry for truth holds the essence of wisdom. As an unenlightened human being, I cry for possessions and earthly success. However, that same devotion I have for the accumulation of power and wealth can be redirected towards the ultimate Power.

Sri Ramakrishna taught humanity that the sunlit path means approaching the Divine “as a child approaches his mother, with the same purity, sincerity, ardent love, and faith, and the Mother will come to you! Call ‘Ma, Ma’; call again and again. The Mother is bound to come.”

Could there be a simpler way? Casting my thoughts back to earliest childhood, memories of my mother were of a protective and guiding figure whose caring presence could never let me down. If I cried, was there anything that my mother would not do to ease my pangs? Likewise, is there anything my Divine Mother will not do to liberate me from ignorance?

Mystic poet-saints over thousands of years have written, spoken, chanted and sung about the overwhelming sweetness accompanying the devotees of God. Like the taste of mango, it can only be felt but not described and it is waiting for us to try it. The Indian tongue has a word for this feeling, Bhakti, the longing for God. This word seems to do far more justice than any English synonym to that sense of overpowering yearning, the magnetic pull of the heart towards its source that is Godward devotion. In many paths, bhakti is not only the means to an end, but it is the goal itself. Having tasted love of God, the bhakta craves for no higher bliss than that.

The most devoted person I ever met was Sri Chinmoy. He was devoted to many things: world peace, physical fitness, a renaissance of spiritual civilization. Most of all, he was devoted to his “Beloved Supreme”. He told us that we too could one day see and feel the presence of our Supreme, who can take innumerable forms for His devotees. Sri Chinmoy would often speak of devotion as the middle step of a process leading to God-union. First comes the divine love from deep in our hearts that expands itself without limit. This love consecrates itself into devotion and finally becomes surrender, when the ego gives up its struggle to be separate from God’s Will.

Sri Chinmoy tells us that Brahman (God) is “indivisible, a complete whole. But through maya, its self limiting force, it has broken itself into infinite pieces. The aspirant's all-surrendering devotion can easily make him whole again, divinely complete and supremely One.” Sri Chinmoy would often say that it is easiest to feel devotion to God through one of his human servants, through a spiritual master. Those times when I have felt most devoted, most enraptured by what I feel to be divinity, has been when meditating either in the physical presence of Sri Chinmoy or by invoking his spirit. Wherever spirituality has blossomed, it has based itself around luminous personalities who are revered as tangible expressions of an Unknown reality. It is through human instruments that God is known, for how else could our minds ever conceive of the Divine? Sri Chinmoy says of the bhakta: “He knows that he is a human being and he feels that his God should be human in every sense of the term. The only difference, he feels, is that he is a limited human being and God is a limitless human Being.”

Wherever spiritual devotion exists, its beauty is expressed through sweet enchanting melodies. Krishna’s flute was said to have awakened the stirrings of transcendental love in all who heard it. Sri Chinmoy was one of the most prolific writers in history. Even so, the quantity of his literature was transcended by the soulful exuberance of his musical spirit. I firmly believe that he composed these innumerable songs so they could spread the world over and uncover man’s hidden power of divine love.

“Devotion in the heart

Is the expansion

Of our Divinity's real life.

Devotion in our entire life

Is the fastest speed

To reach our destined Goal.

Devotion is the strongest magnet

That pulls us to our Eternity's source:

Delight.”

— Sri Chinmoy, from Union And Oneness

Tom McGuire

Auckland, New Zealand

Across the Ocean to Swim or Sink

He was a bear of a man, with a bear-like, straggly grey beard, the last vestige and visage of the Rabbinical life-path his Hebrew parents had probably intended, in a preacher-like occupation—Religious Studies professor and faculty head—secular Rabbi to the hundreds of truth-seeking youth who passed through his lecture theatres and tutorial rooms each year. Post lecture, sermon from the mount of Intellectualism, dozens would congregate around him for curriculum advice or, just as likely, words of learned wisdom. For a while, those many years ago while I was under his tutelage, I felt it my mission in life to tread the knowledge-paved road of academia, climb the spiral staircase of learning’s ivory tower, one heaped stack of books at a time.

He was a bear of a man, with a bear-like, straggly grey beard, the last vestige and visage of the Rabbinical life-path his Hebrew parents had probably intended, in a preacher-like occupation—Religious Studies professor and faculty head—secular Rabbi to the hundreds of truth-seeking youth who passed through his lecture theatres and tutorial rooms each year. Post lecture, sermon from the mount of Intellectualism, dozens would congregate around him for curriculum advice or, just as likely, words of learned wisdom. For a while, those many years ago while I was under his tutelage, I felt it my mission in life to tread the knowledge-paved road of academia, climb the spiral staircase of learning’s ivory tower, one heaped stack of books at a time.

Thus I found myself in his office one afternoon discussing a post-graduate pathway, when a throw-away comment made more of an impression than all the academic advice combined. Like a missing piece of a jigsaw puzzle only I was building, something about this comment fit into place, rang true within the broader tapestry of my life’s finely woven experiences.

“I left home and went to India when I was a teenager, convinced that the world was an illusion. I soon found out that it was very real...”

I was far more interested in this apparently banished, near-forgotten youthful self than the mature one behind the desk before me—the version of my Religious Studies professor that could be ambitious, audacious enough to believe that everything around him, everything he knew might be wrong, than the version convinced that everything he knew was right. You see, I too used to think the world was an illusion, and I too found out that it is real, or at least not to be lightly, easily denied.

* * *

The Boyds were our neighbours for several years, a family of five in a yellow, L-shaped two story house, just over the neatly trimmed hedge from my Mother and I. Mr and Mrs Boyd, their two cats and three “spirited” boys—spirited to their grandparents maybe, highly mischievous to anyone else with two unclouded, unrelated eyes—soon became friends as well as neighbours, parents spending time and company upon gold velvet lounge suite worth a year’s wages to some, watching living room centre-piece walnut cabinet inlaid television set often conversation-piece as well, while children were banished to invite trouble in myriad ways—starting fires in the backyard to test the efficacy of a toy fire truck; firing stones a hundred metres or more down the cul-de-sac street to mayhem and collateral damage unseen, using slingshots made ingeniously and very dangerously from dressmaking elastic and off-cuts of two by four; exploring a just larger than juvenile body size tunnel whose length was never satisfactorily determined because a working party of concerned parents, not as unaware of our childhood havoc as we might have hoped, permanently filled it in.

It was a time when televisions might still be made somewhere other than Japan, and the faux gold lounge suite matching floral pattern wallpaper tracing its way round window and door was fashionable in its own right, rather than in a retro sense, and one suspects, looking back over broader, taller shoulders, that Mrs Boyd, alone all day long in upper middle-class, neatly trimmed and weeded suburbia while Mr Boyd approved mortgages and balanced ledgers in a city bank, might have been quietly going cuckoo, or to use the New Zealand parlance, had a few sheep running loose in the top paddock. Conversations would turn more often to her two cats than matters walking upright and on two legs, and aside from quite magnificently managing the kitchen which produced our Sunday lunches, the rest of her time appeared to be spent assembling kit-set tapestries, cushion covers and floor-mats—all featuring embroidered cats—and reading books more fringe than her hand-crafteded rugs.

One book in particular stands out in my memory, its cover still visible in mind’s eye where others have faded. Funnily enough I never actually read it—at that stage of my childhood I hadn't graduated to the adult section of the library, let alone books on fringe science on dusty, taller shelves—but a few comments made by Mrs Boyd as she pressed it upon my Mother lodged in a very curious mind.

“You know that working watches, thousands of years old, have been found by miners deep under the earth. And that there was once an advanced civilisation in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean?”

Microwave ovens were big at the time, and the conversation soon rotated to plastic container cooking techniques.

Although borrowed by my Mother, I suspect this book was never read by her either, as it unceremoniously became prop under right corner of our living room piano. Impossible to prise from beneath hundreds of kilograms of badly tuned keys and wooden frame, one word, more important than thousands of others unread, was prised from a single, capitalised and bold sentence on a pyramid illustrated, rather crushed cover—“EVIDENCE FOR THE LOST CONTINENT OF ATLANTIS!”

The thought that civilisation could be older than commonly accepted, and, in a broader sense, life be full of hidden mysteries, at an age where—Santa Claus unmasked and tooth fairy banished—life was fast losing its magic, was a powerful fascination to this child—a siren’s call to a shore of promise existing still, just beyond sight. Something felt right in the idea that there was more to life than met a still immature eye, just as it also felt right that “I” had existed longer than my two handfuls of years. Television programs like Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World and Ripley’s Believe It Or Not became weekly tuned to, never missed favourites, watched eagerly for anything to do with lost civilisations, and I spent an entire school holiday mostly indoors, reading every book I could both find and carry home on Atlantis.

It was an age and spirit of curiosity, fascination, even seeking, and I could think of nothing more fulfilling than being an archeologist or explorer, crashing through jungles, sifting through mud and sand, searching needle in haystack like just to capture some remaining proof and vestige of glories lost, knowledge drowned. And if it such couldn't be found, I was desperate to get to heaven, just to finally have the answer to earthly mysteries I assumed none who were living had.

Interests come and go in childhood, especially when one has not the means or resources to further them, and after reading every author I could lay my hands upon, and no few crackpots imitating such, Atlantis slowly sank from my mind, replaced by more age-typical concerns like the momentum and trajectory through the air of foot and cricket balls, or how to acquire music when tapes and records cost weeks of pocket money. 1980's synth-pop and MTV-imagery became my lucre sought for a while.

Atlantis rose again in my imagination several years later when, age 15, summer holidays and boredom turned cohorts and captured interest in idle hands, prompted me to visit a new library where a wealth of books on the lost continent could be dredged. Somewhere, amidst tenuous theories based on yet more theories and scratched together half-fragments of evidence, arose something unsought and unexpected: “psychic” evidence.

Framed in parenthesis as soon as dreamily uttered, mixing together fact and fantasy as readily as hallucination and dream, psychic evidence is empirically the most tenuous evidence of all, but it wasn’t the veracity or otherwise of anything spoken over a crystal ball that caught my imagination, but rather a single idea first discovered. Atlantis, the well-thumbed, often withdrawn book suggested courtesy of a psychic of unknown repute, was the obverse and reverse to our civilisation of present day, opposite side of coin to our physical, materially-centred culture—a civilisation where that which was inner was light to our outer dark of night.

It was heady stuff to my younger self, the idea that everything around one could in a sense be false—that inner landscapes could take precedence, have higher importance than the bricks and mortar of outer surrounds—so heady in fact that I woke one night from fevered, reality shaking dreams, previously stable concepts like ‘here’, ‘now’ and ‘self’ beginning to tremble, the house of my reality starting to subside. It was a two in the morning existential crisis, a wide-awake bad dream, and like self proscribed and administered medicine, I pretty much dropped the ancient civilisation quest there and then. Chopping at the roots of the reality tree is a dangerous occupation when your own reality, barely teenaged, is more a sapling and still growing, and though hugely enamoured of those new found, mind-altering metaphysics, I was still young enough to push to one side something that, neither cricket bat nor football, couldn't be caught or passed in the right here and now.

It would be university before I wrestled with and attempted to wield the axe of knowledge once more.

* * *

Just inside the entrance to the Religious Studies Department, a Victorian era former suburban home encroached and eventually swallowed by an ever expanding campus, next to the main office where students would queue to ask procedural questions or get copies of lecture notes, was a poster of Swami Vivekananda, pre-eminent disciple of Indian spiritual master Sri Ramakrishna, be-turbaned, arms wrapped powerfully across chest, twinkling eyes piercing infinity and far, far beyond from an original poster for his immortal 1893 Chicago Parliament of World Religions address, where, with the simple opening words “Sisters and brothers of America” he near single handedly introduced and charmed the Western world to the colossal spiritual heritage of his native land. Opposite the Indian spiritual giant and atop descending staircase, as if warning of academic failure and some slippery slope that lay beyond, a poster depicting scenes from the Tibetan Book of the Dead—the seven lower worlds, gleeful fiery demons and the torments of hell.

I was on a slippery slope when I entered the Religious Studies Department, and I would wince awkwardly, almost guiltily in front of Vivekananda’s iron, soul-penetrating stare. I had started meditating almost two years before, and after an extended honeymoon period of experiences and near daily unfoldment, was now the living embodiment of the smouldering poster on the opposing wall. Whether tormented for some karmic transgression of a previous lifetime or just the follies of this one, my experiments with self-styled spirituality had lead me down slippery slope to more unhappiness rather than less, confusion multiplied rather than decreased. I had attempted to transcend the here and now, yet was increasingly struggling to live the minute by minute.

You wouldn't have picked my torment outwardly. I cruised through my Eastern Religions paper with ease, answered questions on Hindu deities and Buddhist philosophy almost as easily as if the answers were already written upon the page, but when it came to living, breathing spirituality, to the happiness and joy which even the textbooks will tell you every religion promises as its core, you could say I knew nothing at all. In the quest for self-knowledge I had armfuls of knowledge and nothing more.

* * *

University wasn’t what I expected it to be. While I had drifted through high school with neither inspiration nor enthusiasm, passing but never applying self to anything studied, university I had hoped, in the vague plan of my life that didn't really follow any plan, would change all that, finally be the “it”, golden shore and destination that something deep inside said life could be—something to be inspired by, enthusiastic about, seized with both hands rather than dropped or avoided. I didn't go to university for any conscious reason or aspiration—I had no idea what I wanted to be or do, and had no enthusiasm or feeling of having found what I was looking for in anything offered from the dictionary sized academic prospectus, but I had always assumed I would go, and in the end chose subjects somewhat at random—Philosophy, Psychology and German pencilled into an application form as the lesser of many evils.

I ended up failing everything that first semester, in part because none of the subjects, or university itself for that matter appealed, and in part because for the first time in my life not applying myself ended up having a price. But failure did lead me to finally apply myself in an altogether different direction.

Unenamoured of anything I studied, almost at my wits end and desperate for anything that might give me meaning and hope, I was quite randomly reminded of my passing interest nay obsession with Atlantis years before, and how there had always been one book in particular, source and reference for many others, that I had never been able to find: Edgar Cayce on Atlantis.

* * *

Inside the City Library, past the music section where self-conscious, befashioned youth with dyed hair and knee-high black boots flipped through racks of CDs while trying not to catch the eye of other youths dressed just the same, past the book worms who didn't care for catching eyes beyond those dotted on the page, was the spirituality section, a dusty after thought in the far corner of the second floor where the predominant foot traffic was to the bathroom just beyond. Despite being listed on the Library computer, I didn't find that particular book amongst those lonely shelves—it had been stolen so many times the exasperated librarians had stopped replacing it—but I did find a biography of Edgar Cayce, and within its pages, quite considerably more.

Born to a simple farming family in Kentucky, 1877, Cayce was a photographer, Sunday School teacher and devout Christian now better known as “The Sleeping Prophet” and “Father of the New Age”, who by accident discovered the capacity, from a self-induced trance state, to quite simply explain the miraculous. From yet to be invented medical cures to the history and spiritual destiny of mankind, the trance uttered, never charged for words Edgar Cayce were a total revelation, and he and the truths he revealed became a life-transforming figure for me.

What was the purpose of life? “To become one with God,” Cayce intoned sagely from a sleep like state. How to do this? “Through meditation, and the example of a spiritual master like the Christ” he asserted, with the same voice that could diagnose disease and prescribe cures from a distance of thousands of miles. That was all I needed to hear, the illumining words I had been pacing aisles and scanning shelves to find my entire life. In the midst of nothing at all—disinterested academic failure and discouraging living squalor—I had found my life-purpose and mission. I started meditating the very same day.

In Edgar Cayce and the practise of meditation, I found certainty and surety where previously there had been none, the belief that there was truth in the world and a purpose to life, and that truth, just like knowledge of some lost civilisation, could be found in the here and now. Truth and the ultimate knowledge—self-knowledge—could be found within.

* * *

Somewhere along the way, countless books and myriad authors read—I travailed the alpha to omega of that library’s spirituality section over the next few months—I gained the impression that the spiritual life is, in practical terms and application, more a mixture of self-discipline, iron will and self-analysis than peace, love and joy. With a ready-mixed, perhaps not fully baked combination of the New Age, Eastern Philosophy and Jungian Psychology, I began, together with daily meditation, a Nietzschean quest to make myself into something more than human. It was like Japanese author Yukio Mishima’s odyssey for perfection of the body, but the subtle body rather than body physical—an attempt to sculpt heart, mind, thought and emotion as though limbs out of shape, transform weakness into strength as though training with weights—through repetition and force of will alone.

With its roots in the idea gained all those years ago in a book about Atlantis that the outer world was less real than the world within, I developed my own version of spirituality in which everything in life could be made secondary to will and truth, and began the Herculean task of attempting, a little like the Deconstruction Theory popular in universities at the time, and very much like my world-denying Religious Studies Professor years before, to reduce the people and events around me to something more essential—eagerly sought for, otherworldly phenomena. I had without realising it started down a well-trodden path, the path of Jnana Yoga or “Path of Knowledge”, and a major sub-branch, Advaita Vedanta—the ancient Indian philosophy of Non-Dualism. Founded by the philosopher Shankara in the 9th century, Advaita Vedanta is the belief that the world and all its phenomena are ultimately a “Lila” or play of God, an illusion produced by and inseparable from the workings of the Divine Forces.

While not untrue or mistaken in a philosophical sense, denying yourself and the living, loving breathing realities around you is not the ideal starting point for self-knowledge, and if spirituality can be described as a myriad of different routes up a mountain, the path of denial and negation is hardly the sunlit one. In fact, the path I had begun picking my way over was more akin to scaling a cliff-face, if not traversing a giant ravine.

Constantly digging, dividing, negating and scouring for a glimmer of truth, some bedrock of reality upon which to stand safe and secure upon, I succeeded in nothing more than making myself more and more helpless and insecure. You can negate your family as arbitrary, this life-time only human relations; relegate friends as people unaware, ignorant of truth; push aside the entire world as materially based and imperfect in every way—and root out every trace of same in yourself—but in trying to shed your humanity like the skin of a snake, just like a snake you are trapped on your belly, crawling only in the mud.

The problem with self-analysis is that you tend to miss the wood for the trees, run the risk in turning over rocks of only finding dirt instead of nuggets of gold. Spending your time thinking about your weaknesses and failings is neither affirming nor strengthening, and not at all a basis upon which to build true self-knowledge. Furthermore, in self-analysis you become trapped within the very imperfect, leaky vessel which most needs to be perfected, stuck within the unlit, always tending towards doubt reasoning mind—the limited human mind that is barely capable of seeing or embracing the infinite reality into which we all must grow.

Of course, if I had been following Advaita Vedanta strictly, I would also have known about the necessity of studying under a Guru...

“You want to realise God, but it is through aspiration that you have to realise God, and not through self-analysis. If one expects to go to God through analysis he will be on a very long, tortuous, almost impossible path. The mind is constantly protecting itself by its human logic. If the mind says today, "This is the truth," tomorrow it will say that that very thing is falsehood. The mind contradicts itself at every moment, and when you become one with the mind you just enter into a sea of confusion.”

—Sri Chinmoy, The Hunger Of Darkness And The Feast Of Light, Part 1

* * *

“Yeah hello, I'm calling about the meditation classes advertised?”

The man on the end of the line sounded busy, and despite being the owner of the answerphone’s cheery new age tones and wafting, soothing flute music—encountered on several previously discontinued calls—seemed neither embracing nor interested in conversation.

“They start next week, Monday at 7pm...” ‘Was there anything else?’ the unspoken but implied, impatient following line. I persevered.

“Well, see, I've been meditating for a little while already, and was wondering if you could tell me a little about the course?”

Meditating by myself for two years, at a complete loss with how to deal with the morass of my own making I was stuck within, I was desperate to just talk, swap notes with a fellow practitioner, meet a kindred spirit who might know a little about what I was going through, perhaps be able to offer some guidance or advice on treading the inner road, more muddy trail I was knee deep within.

“On Sri Chinmoy’s path we consider everybody to be an absolute beginner...”

I ended the call none the wiser than before I made it, yet further resigned to the fact that life had, dead ends if not gaping ravines on every side, construed to leave me no course of action but to follow the sunlit path, next Monday evening.

* * *

Waiting for the first night of the meditation course, I read a book by Sri Chinmoy, and the words of the God-realised master struck a chord, rang an inner bell. Sri Chinmoy’s poetic, deceptively simple writing matched, nodded in agreement with everything I had gleaned so far, but my university over-educated mind was unable to grasp the simplicity therein, was prone, like a lecturer, to talk over the top of the deeper, plain-spoken truths on every page.

In the Indian tradition within which Sri Chinmoy has his roots, a single word like “God”, “Truth” or “Love”, said as mantra and repeated countless times, is enough to lead one to enlightenment through realisation of the ultimate truth contained, but if truth was a coin, I was a greedy magpie, too intent on collecting and hoarding than spending or recognising the wealth I already possessed.

Love, devotion and surrender are dictionary words we can all know the meaning of, but each can take lifetimes to fully realise. I read of love, the spiritual heart, God and the soul in Sri Chinmoy’s writings, even had my share of fleeting glimpses of all, but was unable to identify or hold on to any because, like drawing water from the ocean with a woefully tiny cup, I was attempting to do so with the reasoning, intellectual mind.

This is why Sri Chinmoy advocates meditation in the spiritual heart as the safest, surest way, shortcut and golden path to self-knowledge and God. The heart identifies, expands, embraces and loves—it has the capacity to become the very thing it focuses upon. If meditation in the mind is a treacherous, rocky path, meditation in the spiritual heart is safe and sunlit.

The mind knows

That there is a sunlit path,

But it refuses

To walk along the path.

— Sri Chinmoy, Seventy-Seven Thousand Service-Trees, Part 25

* * *

I walked around the city block for a second time, heart palpitating, sweat forming, not from exertion but an irrational, sourceless fear. I had arrived early for the central city Sri Chinmoy Centre meditation course, and every ounce of my being was screaming to turn around and go back home, just forget about the classes, do them some other time.

Meditating by myself for so long, the whole time spent wanting to find and join others who also meditated, I now for no reason any finger could be placed upon wanted to join only myself, as though, no longer looking for truth under rock or stone, the light of sun was far too intense.

In this case, over-practise of mental gymnastics and force of will really did come in use—I simply spoke, yelled over the top of panic and fear, told my mind to shut-up, climbed the stairs to the second story venue as if symbolically reversing down the academic ivory tower.

“Is this the meditation course?” I asked a smiling, welcoming lady sitting behind a small classroom style desk.

“It certainly is,” she said, her smile doubling as she offered me a registration form, “welcome to the sunlit path...”

Jaitra Gillespie

Auckland, New Zealand

Sunless Wood: Sunlit Path

I am absurdly proud of my bookcase. All the books are arranged not according to some abstruse, academic categorisation but rather by colour - black books on the bottom shelf, sweeping through red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, to white on the top shelf.

I am absurdly proud of my bookcase. All the books are arranged not according to some abstruse, academic categorisation but rather by colour - black books on the bottom shelf, sweeping through red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, to white on the top shelf.

When I got back to Auckland from my mother’s funeral I stood before this rainbow of the world’s literature to find something to read. My fingers trailed absently along the black shelf and alighted upon the small, dog-eared volume of Dante Alighieri’s Divina Commedia. I pulled it out. I had read it several times before.

The arithmetic had not occurred to me until I began reading the initial, immortal words of the first canto:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

ché la diritta via era smarrita . . .

Midway in our life’s journey, I went astray

from the straight road and woke to find myself

alone in a dark wood . . .

Mum was 84; I was 42.

Life can indeed seem a dark wood.

I competed once in a fifty-kilometre trail race through the thickly forested Waitakere Ranges. It was winter. The sinuous paths were thick with mud and tree roots. The bush pressed in, the branches hung low across the path. All the competitors were given at the start a map of the route but all got lost. Of a field of twenty, I was one of only four finishers.

The second time during the course of the race that I got lost, I found myself plunging down into a valley far from the correct route on what only wishful thinking could have defined as a trail.

New Zealand was recently declared by the Institute of Economics and Peace in its annual Global Peace Index to be the most peaceful place in the world, and indeed this peacefulness is found not only in society and human affairs but also in the very geological substrata of the country and in its flora and fauna where no life-form is less than benign, no landscape unwelcoming.

However, at one point as I ran, completely lost, on my only vaguely defined path, I took a turn and suddenly that benign atmosphere was gone. An ominous hush fell upon the bush, the sound of birds ceased, the stream became silent, the very light dimmed, and a sense of dread overcame me as my ragged breath disturbed the cold, damp quiet.

I was indeed lost in a dark wood.

Who knows what dark deed had occurred in this spot some time in the brief thousand years of human habitation of our country, or what sinister mysteries oozed from the rocks to so taint the atmosphere.

Dante, lost in his dark wood, lifted his eyes and saw light shining down towards him from a small hill - ‘the sweet rays of that planet whose virtue leads men straight on every road’, the light of the God who lights man’s way.

Long and tortuous his journey towards that light proved to be, but arrive he did at that final vision of the

Light Eternal fixed in Itself alone,

by Itself alone understood, which from Itself

loves and glows, self-knowing and self-known. . .

the Love that moves the sun and other stars.

St Eustace, also alone in a dark wood, attained to a vision of realms of light far beyond the gloomy and obscure realm in which he roamed.

While out hunting, Placidus - later known as St Eustace - pursued a white stag of marvelous beauty. Long was his pursuit through the dark wood, his eye always upon the fleeing beast. With all his power he pursued it through the thickest forest until he found it at bay upon a rock, a light more radiant than that of the sun shining like a cross between its antlers, and, from that image of the crucified Redeemer, a voice: ‘Why dost thou pursue me?’

Placidus fell with his face to the ground, and from the light - ‘I come hither so that by this stag that thou huntest, I may hunt thee.’

St Eustace’s feast day is September 20. The year is oversupplied with saint’s days and feast days and festivals of all sorts. Of all of them it is Christmas that our absurd, secular world has adopted as being of premier importance. Myself, I have long been more inspired by that day two weeks after the razzamatazz of Christmas - the epiphany, the commemoration of the visit of the so-called wise men to the child Christ.

It is a day steeped in the imagery of the light that guides. In the story, these Iranian mystics travel far, following always that light by which God guides them on across the wastes of the world. They keep their eyes always focused on that light.

And so it truly is. However dark may be the woods in which we find ourselves, if we but raise our eyes towards that guiding light, if we, with single-pointed devotion, follow it, we will see that it shines a corridor of light for us. It shines its light upon the tiny flowers at our feet on the dark forest floor. Though it be the tiniest, distant star, it truly creates a sunlit path for our feet to follow.

Barney McBryde

Auckland, New Zealand

Reflections on the Sunlit Path

About the sunlit path, the path of devotion, I could write many things, based upon my long discipleship with my beloved Master and spiritual Teacher, Sri Chinmoy. But what I really want to say is that devotion is the real secret to the spiritual life. Or, in a broader sense, devotion is the secret to life in general.

I have trouble concentrating. I am interested in many things, and so often I go from one thing to another, not really paying much attention to anything for a long period of time. Focus is hard for me.

I’m also not much of a meditator. After fifteen minutes, I’ve had it!

But I love Sri Chinmoy’s art and music and literature. When I look at his beautiful Jharna Kala bird sketches ,or study his songs or learn his poems by heart, I feel I really get something out of it. Sri Chinmoy is a great spiritual Master, so anything that flowed from his inspired creativity is bound to be uplifting, unique and special.

I cannot sit still for a long period of time, but poems like this one really make me pay attention:

MY NEW TASK

When I saw my life

In the silent room of death

I was thrilled.

I smiled because

I was given a new job

By my Lord Supreme:

To discover an oasis

In the spanless desert of death.

Jobless, aimless, helpless and hopeless

No more am I.

No more my heartbeats

A standing jest, derision.

I shall perform my God-ordained task

And become infinity's Dream and

Eternity's Reality.

— Sri Chinmoy, from The Dance of Life, Part 2

I especially like the lines “To discover an oasis/In the spanless desert of death.” The poem is lyrical, but mysterious in its exact meaning. My personal interpretation is that the poem refers to a soul that is about to take human incarnation. The soul is contemplating the advent of its earth-journey and the myriad things it hopes to accomplish for God and for humanity. I have discussed this poem with other people, and I have heard several different explanations which are plausible. For example, the phrase “No more my heartbeats/A standing jest, derision” may refer to someone who, at the end of his life, has received a vision of the fruitful possibilities of his next incarnation. The whole poem literally throbs with excitement. The richness of the language and the gorgeous movement recall inspired passages of David’s psalms or Shakespeare’s greatest soliloquies.

My memories of Sri Chinmoy are like a luminous collage that I continually fit and refit into different combinations and patterns. Especially, I have many memories of Sri Chinmoy meditating at our Saturday two-mile races in Jamaica, Queens. The races were informal affairs, run around a city block that included a convalescent home, a modest neighborhood park and some apartment buildings. Often he would be driven very slowly around the course so that he could encourage the runners with a kind little smile or a sweet, blessingful wave. After the races, we would meditate around his car (actually, one of his attendant’s cars usually- more often than not Vinaya’s battered old Chevrolet), and he would sit in silence and then spontaneously compose a poem which he would sometimes also make into a song.

Some of those poems are simply unforgettable.

From the summer of 2001:

“Mornings come to me with the sound-power of the Unknown.

Evenings come to me with the silence-peace of the Unknowable.

My Lord Beloved Supreme comes to me

Both in the mornings and in the evenings

With what He has, and with what He is:

Concern.”

From April 2000:

“My Lord, My Lord, My Lord!

The Heaven-born fragrance

Of my inner-running soul

Becomes the earth-transforming beauty

Of my outer-running life.

My Lord, my Lord, my Lord!”

His last race prayer:

“The fever of the body

Comes and goes.

May my God-love Heart-Fever

Remain forever and forever.

The fever of the body

Is torture unbearable.

My God-Love Heart-Fever

Is rapture unimaginable.”

(All quotes unofficial)

Sri Chinmoy’s poetry is mantric in nature. This means that we can make fast spiritual progress by repeating his poems out loud. The qualities that the words point to in an abstract way are absolutely, concretely embodied in their very sound.

I remember once, after he had composed a poem and offered Prasad (sanctified food) in the form of vanilla wafers, and he was about to leave. It was a bright, cool summer morning. He paused for a moment, as if lost in thought, and then said that he had experienced many more summers than winters in his life, and that he wished for all of us, his disciples, to have many, many more summers than winters in our lives of aspiration and dedication. Then he became silent again, and I think a sweet smile played on the edges of his mouth, and he drove away after waving at us all.

Sri Chinmoy, beloved Guru, your warmth, gentleness and spiritual grace has enabled many, many people to open up new and sunlit chapters in their life-stories. How can we ever thank you enough? Thank you for lending us your life-affirming Light.

Mahiruha Klein

Chicago, USA

Our members

Stories

First-hand experiences of meditation and spirituality.

Spiritual moments with my grandmother

Patanga Cordeiro São Paulo, Brazil

The Impact of a Yogi on My Life

Agni Casanova San Juan, Puerto Rico

My wife's soul comes to visit

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Running for Peace

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Why run 3100 miles?

Smarana Puntigam Vienna, Austria

Meeting Sri Chinmoy for the first time

Janaka Spence Edinburgh, United Kingdom

The day I recieved my spiritual name

Banshidhar Medeiros San Juan, Puerto Rico

The day when everything began

Bhagavantee Paul Salzburg, Austria

It does not matter which spoon you use

Brahmacharini Rebidoux St. John's, Canada

A spiritual name is the name of our soul, and what we can become

Nayak Polissar Seattle, United States

'When you perform for me, always choose devotional songs.'

Gunthita Corda Zurich, Switzerland

Spirituality means speed

Patanga Cordeiro São Paulo, Brazil

The oneness of all paths - personal experiences

Nirbhasa Magee Dublin, IrelandSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

Growing up on Sri Chinmoy's path

Aruna Pohland Augsburg, Germany

A direct line to God

Vajra Henderson New York, United States

A feeling that something more exists

Florbela Caniceiro Coimbra, Portugal

How meditation helped me swim the English Channel

Abhejali Bernardova Zlín, Czech Republic

Winning the Swiss Alpine Marathon

Vajin Armstrong Auckland, New Zealand

Running a Six-Day Race

Ratuja Zub Minsk, Belarus

Except where explicitly stated otherwise, the contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. read more »

SriChinmoyCentre.org is a Vasudeva Server project.

“My eyes adore

“My eyes adore