Inspiration-Letters 2

A forum for inspired writers with a multitude of backgrounds and interests

Last week I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan. I often go there to look at the work of my favorite painter, Cezanne. To me, his work is inexhaustible in its complexity, richness and feeling. I’m particularly fond of the way he is able to take ordinary subjects- a small mountain, a peasant, an old cottage, and depict them in a way to make them endlessly appealing and interesting.

There is something awesome about being in the presence of monumental creativity, such as Cezanne’s. No reproduction, no computerized image can ever capture the magic of his original work.

Inspiration-Letters seeks to offer interesting and original articles on any topic. Authentic, well-written prose is hard to find on the Internet; and we hope that our magazine may help to fill that gap. We warmly welcome our fellow word-lovers and yarn-weavers to join us in this great project.

The word “letters” immediately implies disclosure or revelation. “Inspiration” ultimately derives from the Latin word “inspirare”, ‘to breathe in’. Taken together, the phrase “Inspiration-Letters” suggests a magazine that features uplifting personal narratives. But, like most literary journals, we’re not seeking articles on just one topic or theme. We’re hoping to offer prose pieces which will appeal to readers and writers of all spots and stripes!

Franz Kafka once wrote that “writing is prayer”. And Jean-Paul Sartre expressed in an essay that we never write for ourselves alone. Without a real or at least an intended audience, the writer is meaningless. I sincerely hope that the stories and articles featured here ring true. Like Cezanne, we strive to offer inspiration and joy by telling the simple truth of our lives and dreams.

Sincerely,

Mahiruha Klein - Editor

Yes, it needed painting badly. In the last five years, the white finish had dimmed noticeably. In a photo of it dressed with snow, the verdict was clear. How could this white house look positively grey in contrast with the gleaming white powder? It looked white enough when I first moved in but time marches on for all of us – houses included.

Upon choosing a house painter recommended by several friends, I promptly found myself on a yearlong waiting list. The business was run by a woman and given that it is somewhat unusual for a woman to own a painting business, I decided I could wait. I felt myself a kindred spirit to her as the first-time owner of a house that did not include the more typical female equation of homeowning as part of marriage or inheritance of family property.

When the anticipated job was only a few months away, I began in earnest to choose colours. Light blue was a favourite among my spiritually-minded friends but that was the colour of the house directly across the street. I could just picture trying to give directions to the blue house and the inevitable resultant confusion. How about light yellow, a colour I had already used lavishly inside the house? Yet the more I researched the topic of exterior house paint, the greater my sense that I better paint the house the same colour it already was – white. That still left the shutters to be decided at least.

While out for a walk or jog, I would carefully analyze the houses in the neighborhood and try to picture the colour of various shutters against the backdrop of my house. I felt drawn to a shade of blue that had an American colonial flavor but I never found this colour against a white backdrop. I would squint my eyes and try to picture it - alas it just didn’t fit. Maroon perhaps? This colour appeared as an accent on many houses in my environs. I came back to the task on each successive neighborhood jaunt because a sense of closure eluded me.

One morning while out running, I stared yet again at all the maroon shutters and told myself how good they would look since my door was already painted maroon. Surely this must be the choice. Unexpectedly the answer came from within. As distinctly as if having a conversation with a person, I heard my house tell me to set aside the matter of the shutters and hear that it wanted to be painted green instead of white. Luckily the house’s choice of colour was not shocking since I do like the colour green. Nonetheless, it certainly gave me a shock in its means of conveyance. Somewhat stunned about what had just happened, I pondered that perhaps a house is as alive as a person in its own fashion.

As I considered it further, it had almost seemed right from the start that the house possessed a spirit which mostly delighted in the righting of its state of disrepair. It badly needed renovations when I purchased it, but I saw nothing but brimming potential in its abundance of windows, a nice yard with trees and the surrounding pleasant neighborhood. Sure enough, its hidden beauty surfaced as renovoations proceeded. And sometimes if too many aspects of the house were changed at once, a distinct discomfort seemed to emanate from it. Perhaps rapid change was just as difficult for houses to tolerate as it often is for people. This sensation is what first gave me the notion that the house had its own personality and presence.

That day when the house made its personality known once again saw the end of my housepainting indecision. I felt comfortable overlooking the voices of “experts” insisting the house should remain white. No, if the house wanted to be green then green it would be. It was settled. Because I hoped to do the house in only one coat over the aluminum siding, the house painter explained the shades of green that I could realistically choose from. Thus, it was painted light green with a contrast of dark green shutters.

Does a story immersed in the mundanity of what colour to paint one’s house and shutters have any redeeming lesson in it? A closer look at my nagging uncertainty provides a clue. This long-lasting uncertainty about what accent colour should go with white hinted that I was concentrating on the wrong choice.

People, places and things have a certain rightness and internal rhythm meant uniquely for their own flowering. If we stray too far from finding this rhythm, we are apt to be haunted by inexplicable discomfort. With tools such as silent meditation and prayer, finding that place of “meant to be” beckons more easily. Along the way, guiding messages will whisper to us from all manner of teachers if we listen carefully. When at last discovering the rightness of life, the all too still breeze of peace finally stirs in the depths of our being.

When I started meditating and intuitive powers blossomed, I never imagined that they would include this type of an inner message from my house. I’m glad I could hear its wishes. The very day it was painted it looked as if it had never been any other colour. Wearing green sleeves, the house continues like a real friend in my life. So don’t be surprised to find that walls do sometimes talk and people do even sometimes listen.

Sharani Robins

Rhode Island - USA

Day Three: Silent Day

We will have to cross the land of death today. Actually, it is not that bad. The potential risk is not reduced, but the immediate danger is. We are, after all, roped together, and we know enough to keep a fixed distance from each other so that the rope is always tight. If any of us should fall into an unseen and treacherous gap of the glacier, the others will hold him until he climbs out. It should be OK…

I only wish I didn't know the scary feeling that the sight of these gaps and their profound black depths offer when suddenly (as has happened to me many times), the ground gives way below my feet and I find myself above a profound black nothing, with only my upper body leaning against some fragile snow-wall of the crevasse, with my legs having no support to stand on or to push against. But unfortunately I do know what this feels like and I would do anything to avoid repeating those falls.

We walk upwards in utmost silence, amidst snow and ice and yet more snow and dirty white slopes framing this deserted landscape of the upper, vertical part of the glacier. There is nothing else but us, five little slowly yet rhythmically moving dark dots on the back of a seemingly mild snow-covered field. We represent the only life here in the realm of non-life and this makes us more vulnerable, more exposed to all danger. This is a place where one doesn't stop, doesn't wonder, just walks through with utmost cautiousness. I am totally one-pointed and, after a time, my eyes learn to scan the huge tables of snow lying before and beneath my feet, the simple change of its shade indicating unstable or more reliable sections.

I breathe deep, trying yogic ways of breathing, keeping the inhaled breath inside as long as possible. Not easy as we are moving uphill at a steady pace!

And then comes my Guru's advice. While an automatic scanner machine in my head searches for possible risky spots on the snow-covered ground before placing my next foot on it, his voice approaches my heart. “Concentrate on your weight, imagine you have no bodyweight,” he says.

My new mantra suddenly becomes "I am of air, I have no weight". It is fantastic, and moving becomes wonderfully easy. I feel so light. It must be a glimpse of the ecstasy Saint Peter felt when Jesus made him walk on water. I walk with no weight, in intense concentration. I left my bodyweight at the feet of my Guru. Even the weight of my rucksack! A field comes that I cannot avoid; I clearly feel it is only a snow bridge with a hollow gap beneath it. I just have to cross it, the way our guide did it seven meters before me, ten seconds ago. I am walking on a thirty-to-fifty centimeters thick layer of snow stretching above absolutely nothing. But I have no bodyweight anyway. Like a butterfly, swiftly touching the ground I walk across. It feels like walking on water. It actually is walking on water. Two meters later when I feel that I am walking again on something more solid, I try to extend this lightweight feeling to the three companions who are behind me.

Too late. A pull of the rope around my waist and a sudden outcry indicate that the snow-bridge broke under the one right behind me. I hold the rope tightly with my right hand. The leader pulls me strongly towards himself, away from the gap and yells at me in his unusual (at least to my ears) Swiss dialect that I immediately understand: “Move on, move on!” The person behind me safely and really quickly pulls his lost leg out of the gap while I cautiously place my feet one after the other. I offer a second of gratitude to the Supreme Protector. We continue as if nothing had happened.

I won't tell you more of these little happenings, as the journey (across a glacier upwards, then across a pass at 3500 m, then across a glacier downwards and then across a huge moraine and debris of zillions of stones scattered on top of each other) lasted for hours and hours. There is yet one thing I have to tell.

While still at the beginning of this day's journey, still struggling our way up the glacier at the western versant of the mountain, scanning every little place before stepping on it, I remarked the tracks of a single pair of crampons. Whoever wore these crampons must have had an extraordinary sense of the glacier, must have been absolutely confident in distinguishing the places with hollow gaps underneath and the safer sections. There is no hole on the ground nearby these tracks. On a glacier trek one usually sees deep holes all over the pathway across the glacier, indicating that someone (well, at least someone’s leg) had fallen inside when a snow-bridge didn’t resist his bodyweight. The tracks I see here skillfully, amazingly, avoid all risky spots, and lead to reliable snow-fields. After a time, as my own experiences accumulate in recognizing these, I understand that I can perfectly trust these tracks. Also, the leader, just before me in the rope, does the same thing. We follow the tracks and walk quite safely, although extremely cautiously, without a single word or outer sign of communication. Then a thought suddenly puzzles me.

In the hut there was no one else who chose the same route as we five did. All the other climbers went for some other destination today, we being the only ones having planned summit “attack” for the next day. We left the hut before five with our headlamps on. Simply no one walked that path before us today. But these tracks are totally fresh. Usually only half-day old tracks remain visible on the snow-fields of a glacier, for everything that is older than that vanishes when the daytime sun melts the upper layers of snow and the night-time cold freezes a shapeless wet snow again. These crampons have so skillfully walked the track THIS very morning. But the only direction they could have come from was ours, the spikes of the crampons also point that way, and yet we are not aware of anyone else having adopted the same route or same plan before us that dawn.

The other strange thing is that there is only one pair of crampons as if only one person had walked there, or as if two people had managed for hours and hours to perfectly step exactly in each other's tracks, having exactly the same stride for each and every single step. It is impossible. There physically cannot be two people stepping so much alike on such a long distance. And why would they do it? Also, if a single person walked this path here this morning, was he mad? Crossing a glacier alone, completely alone, is madness. Even if this one HAD mastered the gaps and slopes of the glacier then: Who was he, why was he alone and where was he going?

I start sobbing when an answer flashes through my mind. It was neither a solitary climber, nor a madman. It was someone meant to lead us across the harsh sections of this glacier, someone who knew the way and wanted to spare us from erring in vain, someone who wanted us to cross it safely. Therefore he came, marked the unknown path for us with these reliable signs and when we finally crossed and turned to another path, a known road that led to our next hut, he simply vanished. He was sent to lead us through the tough sections…

Day Three: Ceaseless efforts and hitting the wall

The longest and hardest day so far. I slip down a slope of the glacier in the melting, wet snow, but thank God, I manage to stop myself before it comes to pulling the rope. Unlike the others’, MY crampons do not have a snow-repellent plastic bridge and every once in a while I find myself walking on small snowballs as the pudding-like snow accumulates and sticks to the metal. And there is no time to clean it off.

We rhythmically move down a very steep section with visible cracks and gaps all over at the edge of our path. I have an increasingly uneasy feeling, something I cannot explain. I start calling on God to prevent whatever bad thing is about to happen. And then suddenly I hear my own voice shrieking in German ‘Please, slow down a bit!’ It has an immediate effect, but it shocks me: I would have concealed my fear and worry forever, rather then so non-politely yelling at someone who has much more experience on mountains. I would never ever have revealed what a difficulty this fast descent with crampons was for me. And here I am crying out. At that moment when Adrenalin-production is at its top, my soul pops up with gratitude. Without any proof or tangible indication I know that in a few seconds or minutes I would have stumbled and fallen, pulling at least one more of us to roll down towards the bottom of this slope. This forgetful, spontaneous, self-control-less instant saved me at the price of giving up my pride and “I can do it”-obstinacy. Again, I have to admit that I am slow, overcautious, faltering and what not… I am not a climber, just an office employee who goes sometimes in the mountains. Nobody minds it however. And this time there is no fall.

The two glaciers and especially the second moraine take a toll on my fitness and good humor, not to speak of my nerves. Another two hours of erring amidst and on top of a chaotic array of stones and rocks and boulders (I have never seen a bigger chaos than what a glacier’s lower body can produce), of jumping across crevasses and breaches, of guessing the right direction in a thick fog, and I feel finished. The muscles of my right leg and thigh ache at every step. We still need to focus, sometimes we take the crampons off, sometimes we put them on again, sometimes we walk with tight rope, keeping an equal distance between each two of us, sometimes we get closer and take the rope in hand. Focusing on each step is crucial as all we walk and climb on is nothing but heaps of stones of various sizes, thrown on top of each other, as it were, by a furious giant once terribly in a hurry. Most of these stones move as we step on them or are unstably lying or actually hanging on other stones and there are smaller or bigger empty spaces between each two of them. None of us wants to sprain his or her ankle, but we have no time to think twice before placing our foot on the next stone. It is God’s grace that we safely make it through this multitude of stones. But the kind of feeling that marathon runners usually have after thirty kilometers starts to prevail. I know that I am about to hit the wall.

From 2800 meters we have to climb up again an arduous pathway to 3030 meters. Here the mountain guide proves that he has excellent reflexes. At a place where two- to-three centimeters thick ice layers are covered by muddy talus I slip back again, but he immediately halts me with a strong pull. I had fallen less than a foot (33 cm) and in two seconds I find a fixed spot for my legs to take my bodyweight off the rope. It is really reassuring to climb with an expert like this fellow.

However, during the last few meters I already feel very sick and when we arrive to the last hut all I want is an Aspirin.

Later on, towards the evening, when I am recovered I go out again to sweep the nearby mountains with a glance. Phenomenal views await me both upwards and downwards. I finally spot our goal of the next day, the calm and gentle, so called “easy” four thousand meter summit. I am absolutely not pleased by the thought that it is top to bottom wrapped in glacier and only its last two meters are rock.

Day Four: Be Brave!

This day I wake up with my Guru’s voice in my inner ear. I actually get up and not wake up, for I couldn’t sleep all night, so I am happy when finally the first batch of climbers leaves at three o’clock. We have another hour to rest, which I can use for prayer and meditation.

I had dreamt that my teacher, Sri Chinmoy, approached me and said, “Be brave!”- no more and no less.

I remember that in China when I had a wonderful sojourn with my Guru, I offered a picture with a poem on it as a gift (Prasad) to everyone. The poem was the following prayer by Sri Chinmoy:

“My Absolute Lord Supreme,

I must concentrate soulfully

On what I am doing

And not on how or why

I am afraid to do it.

No fear!

Only Your Compassion, Your Compassion, Your Compassion

Is what I need

And what I am

And what I shall forever be.”

- Sri Chinmoy

I remember that just the next day he composed a song with the refrain “No fear” and the refrain “Be brave!” I hadn’t thought of this song since January but now it sings itself in my head. Later on, at the time of writing this story, I am rifling my diary page of January 1, 2005. I scribbled just a couple of sentences my Guru told us that morning, including this sentence (and I am definitely paraphrasing): “I am telling you, fear overcomes you, but if you challenge fear then fear disappears, it will go away.”

So this is the song, and its line: “Be brave!” accompanies me while stumbling from stone to stone in the dark morning across another glacier section of the mountain. I am worried not to hurt my ankles, not to slip down, not to get injured today of all days, just hours before we start our pilgrimage to the summit that I may or may not reach. Then again, I leave it up to God, after all, if He, oh sorry, She doesn’t want it, there will be no way of getting up to the top. As a recompense I can have a glimpse of the first dawning hues of the sky just behind and above the Weismies mountain and then of the sea of clouds floating amidst various chains of mountains. None of us speaks a word, there is a solemnity in our silence and I categorically feel like never in my life. The only feeling I could compare this twilight to is the tight stomach feeling on mornings before my hardest exams. What will happen to me today?

The rest of my tale is a merged memory of our struggling collectively up and up, higher and higher on a steep glacier aggressively caressed by a zillion kilowatt strong sun on its other side and a mild forty kilometers per hour wind on our side, a wind that compels us however to put on all the warm clothes we have. I remember giant crevasses we pass by. In some of them an entire bus could have been thrown without touching its edges. At places I see big broken vertical fields where massive blocks of firm snow had fallen from leaving behind the view of ten-fifteen years of snow layers, stratum upon stratum. At places I see the unfriendly but familiar holes in the snow, reminding me that I walk on a glacier, quasi on empty space covered with melted and refrozen (or “re-melted” and “re-re-frozen”) pudding-like snow. At places I see nothing, I just feel an intense pain in my right leg. I am yearning, craving, moaning for just twenty seconds of rest, just to get the cramps out of that poor muscle. But mountain climbing is not like marathon running because here you cannot just stop whenever and wherever you want, no helpers will bring you food supplements, no massage is given and there is absolutely no way of lying or even sitting down. I sigh and move on, constantly upwards on a sometimes 60-70 degree steep (!) slope. I wonder how on earth the snow stayed there. Normally something that is as steep as this would be an avalanche field and it would definitely not bear a 15 meter thick layer of snow. The rope-head teaches me a new technique of placing one crampon before (and above) the other, something that is less tiring for the legs. But it is too late. I grow tired with every new step. At the same time I know that we have less than five, four, three, two hundred meters of altitude difference, which means that the summit should be within reach.

I think of my Guru again and he comes to my rescue. Breathing in a little rarified air is no longer a problem and breathing so consciously definitely helps. I am a bit revived, although I still move utterly slowly. Let us not dwell on details.

I ask myself why I haven’t opted for table tennis or chess instead of this silly self-torture. At this moment I am yet unaware of the fact that just two hundred kilometers away, my dear friend Dharmaputri, who is a much more advanced and accomplished climber (and also, much more modest than I am) asks herself something very similar while battling with her ice axe against the north wall of Bifertenstock, an alpine challenge not too many women would be able to tackle. She in fact decides never to do that again, just to wander in the hills and knit nice pullovers at home.

The world changes the moment I reach the ridge in the footsteps of the guide and the splendid and spectacular view of anything that can be called a mountain range in Switzerland, Italy and France is below my feet within a distance my eyes can cover. I no longer yearn to play table tennis in a warm club hall. A little later Dharmaputri also reaches the top of that awfully unattractive block of a mountain and decides to postpone knitting to her older days. Things are back in the right order; I am at the right place in the right moment and I want to cry, it is so magnificent. I sincerely enjoy the pushes of the wind and the snow it blows and throws in my face. Around us two colors dominate: white and blue. Familiar.

Twenty more meters and we are at the summit cross, at 4027 meters. One of the most famous Olympic champions of my country wrote once “Only the winners are allowed to cry”. I am glad that finally I can allow myself to cry. I inwardly and quickly bow to the Crucified one looking down from this solidly fixed cross and … I have to fight my tears back as the leader shakes my hand to congratulate, then shakes hands with the others, then everyone with everyone. The solemnity of the moment is gone, I am again in company of four more people and a minute later in company of two more, the French climbers who have summited by a difference route. The summit is too small for seven people, even the five of us had to gather tightly, the ridge itself is just large enough for one person to walk along safely, therefore very soon we have to start descending. But before that I can measure the real size of the Feechopf, Rimpfischhorn, Alphubel, Matterhorn, the Mont Blanc, the Dent Blanche, the Monte Rosa, Jungfrau, Moench, Aletschhorn, and two equally appealing nearby mountains, the easier Breithorn and the beautiful Weismies. Plus hundreds of named and nameless summits, chains, glaciers (including the ones we crossed a day ago), and also cloud-seas concealing Italy and France below their white puffy layers. The neck and head of the Mont Blanc are enveloped in a dark grey overcoat and the closest mountain to the north from us also generates thick and long dirty clouds of the same type. We are lucky to have reached the summit in time, and now we have to leave it well in time, before those clouds reach and hide our slopes. We start a descent and I am increasingly sad. I had thought that I would be the happiest person on earth if I managed to get to the summit of my dream-mountain and now I am a bunch of nerves trying to make it down the steep slope without slipping off and rolling away, pulling also someone else tied in the same rope.

Minutes after we reach Europe’s highest functioning ski trails somewhat lower at 3500 meters and before we take a cable car down to the village, the summit wraps itself into heartless, unplayful, grey clouds. The gift I was given at 10:43 a.m. today is no longer available to others, not even to our own eyes. In the cable car and later on in the train I silently cry. Then I leave a message on someone’s answering machine.

I remember the words of another mountain guide who taught me a glacier course earlier this year: when all cameras fail, the digital cards are full, the battery goes down, the film runs out or the lens breaks, there is still another camera that will perfectly work and no human can ever erase whatever that camera recorded. That camera is the heart. I try to stock as much as possible from all I have seen in this little lotus-shaped Minolta of mine somewhere deep inside.

Four days later I cannot but think with utmost gratitude of my spiritual teacher who helped me through these strenuous days; who understood, inspired and encouraged me, gave me very good breathing tips and meditation exercises.

I also offer my most sincere thanks to Richard, the rope-head and mountain guide who performed his duties as a real service, with perfection, skillfulness and enduring patience. I am sending warm thoughts to my friends Dharmaputri, Anugata, Kripabindu, Divaspati and others whose capacities are far beyond mine (for them this would have probably been an easy trip) and whose inspiration and precious advice I always gratefully accept. Special thanks once more to Dharmaputri whose home was always open to me whenever dirtily, filthily, I descended from the Alps to take a hot shower before embarking on my journey home.

Days after this great altitude tour, when I type these words, I know that saying ‘yes’ was worth it. It was the right thing, the answer I HAD to give. Not because I have seen the world a little from above and I have come to the conclusion that the really great and remarkable things can only be seen from up there or that the world is beautiful if looked at from 4000 meters. No, it is actually the fact that those five days of hardship and those five months of senseless self-torture (uphill running, push-up tryouts, repeating knots, etc.)- were in and of themselves my greatest rewards. According to an old advertisement slogan “no one sent home breath-taking pictures from Base Camp”. Yes, the summit certainly offers a better view if you can attend its call and if Grace taps on your shoulder.

Please, all of you who cannot imagine why we take such risks, try to understand us when we say that you don’t know what you’re missing!

Kamalika Györgyjakab

Hungary

High in the sacred mountains west of Xian in south-western China we trekked to the summits of a number of massive granite towers that form part of a rugged mountain range over 2,100 metres high. In these remote and isolated alpine regions high above the farmlands below Taoist monks and nuns practise their ancient meditative disciplines, as they have done continuously for over 3,000 years.

Living a solitary life in isolated temples perched precariously close to the edges of these vertical rock towers, many of these humble devotees have lived in the mountains for more than forty years. Chinese history records that generations of Chinese Emperors continued their summer schooling high in these wind-swept mountains, trekking great distances to study with these revered scholars.

Down in the valley below we entered the main temple complex after passing beneath an ornate archway that lead us along a climbing pebbled pathway. Climbing still higher we passed over narrow stone bridges, built over a clear mountain stream, then higher into the cool mountain air we passed by ancient temples carrying the weight of winter snow.

Continuing our trek we entered a narrow valley, winding its way deeper into the rock masses. Frozen waterfalls held by the freezing temperatures, hung above us like a pale blue curtain. Dwarfed by the sheer height of the slabs of rock that towered above us we quickly began to climb onto a much steeper and narrower track, hand chiselled into the solid granite bedrock. These steps continue all the way to the top of the highest summit, testimony to the hundreds of years of peasant labour who chiselled these narrow secure footholds. As we steadily climbed pausing only to catch our breath and take in the vista, we noticed further temples much higher above us.

Many of the track sections are nearly vertical, a similar experience to climbing a ladder. In these precarious areas labourers secured hanging lengths of linked hand-forged chains to steady yourself as you slowly climbed, carried loads or rested. In places the track is also extremely narrow as it passes between vertical rock slabs, here the pathway walls have been chiselled wider for safe climbing.

All construction materials for the temples were carried by back up this steep track by peasant labourers. This timeless tradition still continues today as all supplies for the monks and nuns are still hand-delivered this way. On the day we climbed we stood aside as two peasant farmers each carrying an overly large hand-carved wooden lounge chair ropped to their backs passed us on their ascent, a days labour for A$20 for the climb - we wondered how they managed to squeeze between the narrower sections.

High on the sheer rock-slabs monks have hand-chiselled shrines into the bare rock face. Beginning as a small arched entranceway each opens into a large domed room, complete with a shrine, Taoist figurines, a simple wooden bed, intricately carved ceilings and bare walls. Outside overly large engraved Chinese calligraphy characters mark the entrance. To excavate these shrines monks would lower themselves hundreds of meters by hand-made rope down onto the vertical faces from the summits above. Access to these exposed shrines is now up long chiselled step-ways and their hanging chains.

On my second visit to these alpine heights it began to snow, the peaks and valleys filled by mist and swirling wind-driven snow. Climbing by myself in the cold mountain air close to the highest temples I suddenly heard the hauntingly beautiful sound of a flute. I paused for a while and after clearing the snow away from a granite boulder, I sat and quietly listened. This was a very serene moment for here in the peaceful mountain atmosphere, removed from the world and surrounded by fresh falling snow, I quietly meditated allowing the sound of the echoing flute to lift me into a sublime and deep silence. Judging by the depth of snow that had fallen onto my jacket, this experience continued for a long time.

Shortly afterwards I rounded a bend and saw a Taoist monk sitting quietly at his shrine playing his simple bamboo Xiao. Undisturbed by my presence he continued, I smiled and quietly turned away continuing my journey into the falling snow, carrying the haunting sounds of this instrument deep inside my heart.

On my return to Xian I was given one of these flutes by a fellow student of Sri Chinmoy's. I was so thrilled with the kindness and generosity of this gesture, it meant so much to me, the richness of the whole mountain experience, the monks and their simple lives instantly came back to me. But I had never played a musical instrument before, but I wanted so much to learn!

So back in Australia, I looked up the internet and learnt how to play some basic tunes using simple fingering positions. One of these songs is a beautiful Chinese folk-song called - Dragon Children, its still one of my favourites, because it embodies the whole China experience. I had the pleasure of playing the Xiao for some family members, a Chinese student was present at this family gathering. After I nervously finished playing the student very excitingly stood up and yelled in broken English 'Dwagon Child', I nearly fell over, she actually recognised what I was playing, or perhaps she was being very polite, I think the latter, still it was a lot of fun!

What better way to continue the meditative mood of the Xiao, than to now learn how to play Sri Chinmoy's music. I can't begin to describe the total joy and delight this now gives me. I play for approx.1 hour each day, learning more and more songs. Simple they are with my very limited musical capacity but nonetheless, it has enabled me to access a deeper aspect of my spiritual self, and it has given me a totally new understanding of Sri Chinmoy's spontaneous capacity to compose and play.

Who would have thought that it took a trip to China, then a steep trek into these isolated mountains and then a 'chance' meeting with a Taoist monk playing the Xiao to help me fully appreciate the overwhelming joy and beauty of Sri Chinmoy's music - I guess I'm a bit slow!!

Thank you Sri Chinmoy for your whole China experience and a simple bamboo flute that has brought so much into my life and the total simplicity, beauty and power of your music.

I remain eternally grateful to you.

Gratitude, gratitude

Sahayak.

Further research on the Xiao has found that it is one of the oldest Chinese instruments found in excavations throughout S.W. China, dating back around 3,000 years. Approximately the same length of time the Taoists have been living in these sacred mountains!

Sahayak Plowman

Brisbane - Australia

Saturday mornings I eat breakfast at a diner just off the King’s Road in Chelsea. It's like home from home. A cosmopolitan place; you see an interesting cross-section of people there, Europeans, locals, musicians, actors, families, the occasional star. Nobody pays much attention to anybody, yet the ambience is great. The superb food is inexpensive; portions are excellent. The manager and waitresses greet me like an old friend. They are mostly Hungarian. I like them so much.

Just up the way and round the corner, at that stretch of the King’s Road, there are large London Plane trees every twenty feet. Perhaps a lifetime ago those saplings should have been planted further apart. Now the confident branches grow into each other, overhang the road and scrape the buses and tops of lorries.

I always park my bike in the same place, chained to a tall iron post, between two of the huge interlocking trees. Today there is an open-backed lorry parked in the road, which has been sectioned off by bollards down to one lane. There are two guys on the ground and two harnessed in the trees, all with sound-proof headphones. Chainsaws are screaming, bits of wood flying, branches tumbling, sawdust in the air. I go to lock the bike - they haven’t cordoned off the pavement. One of the guys on the ground looks at me through sawdust-covered goggles and shakes his head, as if to say, “That is not a good idea.” The men in the trees stop sawing, glance down, then at each other and also shake their heads. I’m not about to move the bike, although it is brand-new. Something defiant makes me just lock it and walk away, since I have been doing that with various bikes for years before they got here. The chainsaws start buzzing and snarling again. The traffic is backed up; by now the men have moved further out along the overhanging branches and the ground crew have to close the road altogether. Cars are hooting angry horns; traffic coming the other way has stopped. As I leave the pavement is immediately cordoned off. Then a wood-chipping machine in the back of the truck is switched on, and the noise of the branches being processed adds to the cacophony. Walking down the side road I conclude it was stupid and dangerous of me to act as I did. By the time I get to the diner I’ve resolved that small dilemma by deciding it would be even dafter to return and go through the cordon to move the bike.

I have a great breakfast, read the Saturday papers, chimp through a week’s photos on the digital camera, then over coffee talk philosophy with the manager. Coming out of the restaurant an hour and a half later I realize I don’t have McGuffin, my old Scottish scarf, which is forever being lost and found again - once it was gone for ten months. I return to the diner, but it’s not there. I walk up to the main road, having forgotten the entire tree-trimming event. Turning the corner I stop. The trees look stark and bare, like giant shorn-shocked kids just out of a Leviathan barber shop. The road is so peaceful now, there is no traffic. The cutters are nowhere to be seen; they have gathered up the severed branches and have moved the bollards and cordons. The lorry has travelled elsewhere, along with all the apparatus. I stand and stare, just gazing in the silence, then experience an acutely strange sense of being in this world, of perfect place and composure, in my time and on this earth. I’m on my way to somewhere, but I am also exquisitely balanced in a timeless moment. My new blue bicycle, upright, equidistant between two clean bare trees in the pearly October light. A soft woody fragrance pervades the autumn air; a fine film of sawdust coats the empty pavement and the bike. There on the saddle, neatly folded, McGuffin, the missing scarf. Perhaps the woodcutters put it there. Who else would have known it was mine? I am humbled by the kindness of those to whom I was indifferent. The realization is obvious but somehow profoundly reassuring: events unfold when we are not here. They’ve always done so and always will. The camera is over my shoulder, yet the shutter can be but mute to such a mysterious sensation, this mis-en-scene.

Skyward, the light clouds darken in the west to charcoal grey. Pausing, I decide to leave the bike and catch a big red bus up to town. It’s dark when I return under a new compact umbrella in the last of a Saturday’s rain. All the sawdust has been washed away, the city lights and bare trees reflecting in puddles. The pavement, the road, an ultramarine bicycle - everything looks wet and shiny in my freshly-minted world. A night chill is setting in, but the old Caledonian scarf is doing its job well.

Pavitrata Taylor

London, England

The 2002 Philadelpha Marathon was special for me for a lot of reasons, but two stand out in my mind.

I spent the night before the Marathon with my old high school friend, Adil. We hadn’t seen each other in years and it was lots of fun catching up with him and reminiscing about the good old days. We watched old, beloved Dr. Who episodes together and also quizzed ourselves in SAT vocabulary.

Adil’s brother, Ibrahim, was away at college so the family gave me his room for the night. As I was preparing for bed, I noticed a white yarmulke on the nightstand. When I looked on the inside of the yarmulke I read:

“In honor of the wedding of Sharon Smith and Mordechai…”

I remembered Sharon really well because we had both been members of our high school’s Model United Nations club. We had even been chosen by our team captain to represent Japan on the “Security Council” during one session held in Princeton (we had placed third out of thirty or forty delegations). Now she was married and probably a bio-engineer, and I was waiting tables and running marathons.

The second thing I liked about that race was running through my old hometown, Philadelphia. I actually grew up in an obscure suburb with an unpronounceable Welsh name (think of ‘yydych’ and you’ll get the idea), but Philadelphia was always my home city. I rooted for the Eagles and the Phillies and mourned with the rest of the city as they lost, and lost, and lost- year after year.

A famous runner once said that there’s something magical about the streets of Philadelphia. I guess he’s right, because I’ve never run a marathon as fast as I did that year. I felt that the city itself was gently pushing me to go faster, to run lighter and more freely. When I ran past Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, I felt such joy. Here’s where it all began- the essential idea of human rights that was so powerfully articulated by Thomas Jefferson in his great Declaration.

Philadelphia is a city of such stark contrasts- beautiful skyscrapers next to cardboard shantytowns, gracious museums and gardens sitting next to blocks and blocks of industrial fossils. It’s a strange, haunting place.

Philadelphia marathon watchers are so encouraging and kind. At mile nineteen I slowed to a walk, exhausted and sad. I took an energy bar and ate half of it and immediately felt strong again. When I resumed running, a family of spectators roared with approval. I smiled at them and they smiled back with such open admiration for me.

The Philadelphia marathon was a wonderful chance for me to connect with both my own past and my country’s history. And I was so happy to have had the opportunity to offer homage to my home city, ever-remarkable in its understated beauty.

Mahiruha Klein

Philadelphia - USA

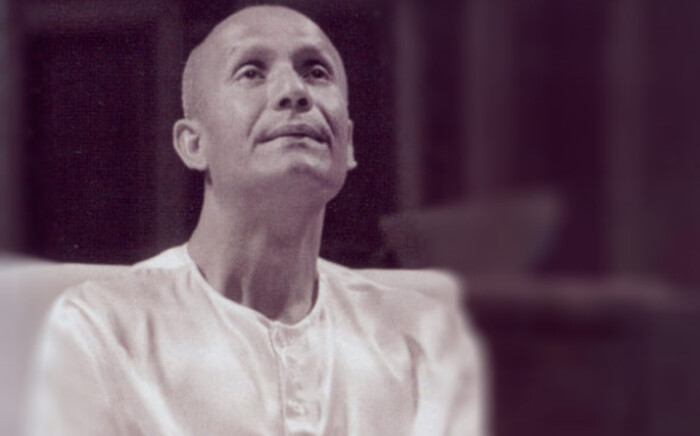

Title photograph and sculpture by Ed Silverton

Our members

Stories

First-hand experiences of meditation and spirituality.

If a wish comes from the soul, it will be granted

Kamalakanta Nieves New York, United States

I was what you call a classic unconscious seeker

Rupantar LaRusso New York, United States

A spiritual name is the name of our soul, and what we can become

Nayak Polissar Seattle, United States

Spirituality means speed

Patanga Cordeiro São Paulo, Brazil

Reflections on meditation

Janaka Spence Edinburgh, United Kingdom

The Ever-Transcending Goal

Preetidutta Thorpe Auckland, New Zealand

The Peace Run visits Oxford

Tejvan Pettinger Oxford, United Kingdom

So much longing, for something

Pushpa rani Piner Ottawa, Canada

Meditation: Touching The Infinite

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Celebrating birthdays at Guru's house

Devashishu Torpy London, United Kingdom

Akuti: a pioneer-jewel in our Centre

Akuti Eisamann Connecticut, United States

The first time that I really understood that I had a soul

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

President Gorbachev: a special soul brought down for a special reason

Mridanga Spencer Ipswich, United KingdomSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

How Sri Chinmoy appreciated enthusiasm

Prachar Stegemann Canberra, Australia

Getting through difficult times in your meditation

Banshidhar Medeiros San Juan, Puerto Rico

Spirituality - the most fascinating subject on earth

Laila Faerman New York, United States

My well-scheduled day

Jayasalini Abramovskikh Moscow, Russia

My first impressions of Sri Chinmoy's philosophy

Lunthita Duthely Hialeah, United States

Where the finite connects to the Infinite

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

No prior experience needed

Samalya Schafer Berlin, Germany

Except where explicitly stated otherwise, the contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. read more »

SriChinmoyCentre.org is a Vasudeva Server project.