Inspiration-Letters 4

Arts Issue

Dear Reader,

It’s a famous image; I knew it from books long before I ever saw it. But there was something haunting about being in the very presence of this 4,000 year old sculpture, created by a genius whose name I will never know.

The modern artists, especially Picasso, have pointed to the arts of the ancient world, and also of Oceania and Africa, as an important source of inspiration. That’s not surprising as great art has always celebrated and strengthened our human oneness.

To be a human being means to have a constant thirst for self-transcendence. Through art we seek truth, contact with the divine or simply a broader understanding of life. My meditation teacher, Sri Chinmoy, has created thousands of paintings and sketches which appeal to me through their sheer simplicity and harmony. Like the artists of the ancient world, Sri Chinmoy allows himself to be a channel for a higher force to express itself. He creates, also, for the sheer joy of creation. What a breath of fresh air in our mercenary global art scene!

We are all artists. I think the simplest form of art is to laugh. It’s amazing that, confronted with the hard facts of human existence, if ever we can laugh at them. Humor, like art, transcends time and culture. Great art makes us humble, but it very often also makes us laugh at the amazing mess we “higher” animals make with our meddling in nature’s plans.

I hope the pieces here inspire you as they have inspired me - to see the whole world inside your heart, and all human history encoded within Keats’ magical lines:

Beauty is truth, truth beauty - that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. (From “Ode On a Grecian Urn”)

Mahiruha Klein EditorMyth And Moment

by Jogyata DallasPhotography! Now there’s an exotic theme and intriguing challenge for the bluestockings and literati of Inspiration-Letters. Next month we’ll be asked to ‘write a passionate rebuttal of Stephen Hawking’s gravitational entropy theories on the Big Bang origins of the universe’ or something equally unpredictable – all to keep us on our toes.

Come to think of it, though, I actually have owned a couple of cameras over the years. The first I left under the goalposts on a rugby field while a group of us rushed up and down the field shouting at each other ( yes, playing frisbee) - when I returned for my camera it had gone, disappeared out of my life with it’s happy, morally bankrupt new owner. The second was given to me very generously in New York by a friend and I spent the long flight home swotting up on the instruction manual - when I got back, thoroughly expert in all aspects of it’s functioning, I found it didn’t actually work. But all this at least qualifies me to say a little on the subject, doesn’t it?

We take our camera and peer through a small rectangle at the fluid passing of life unfolding all around us - a white swan moving silently as a paper boat on a dark lake; a group of huddled friends posing on a cold mountain; the sun falling slowly into the beauty of evening clouds. Images and memories, immortalized moments salvaged from the long sweep of time.

I like the sepia brown, out of focus, grainy photos of the box-Brownie era more than the realism of today’s photos with their painstaking fidelity to detail and cold clarity and precisions of colour. The former are more useful and thought provoking and convey a sense of time passing and the mythology of our lives. Here’s one of the infant Jogyata circa 1957, my runner-up entry in our Auckland Sri Chinmoy Centre’s fiercely contested ‘Most Beautiful Baby Competition’ - cute as pie with my button nose and dimples all over and brown cardy. Grown people have been known to sigh. From different stations in time we stare at each other, me and I, one looking forward into the unknowable future, one looking back at what that future held and became. You wonder, how far have I come, what have I learnt, what other things lie waiting? What a long journey from there to here where I find myself now. Every single atom of my body is different. Holding the photo in both hands and staring at it, trying to work out in what sense this was ever me. Like a surveyor’s peg struck into a landscape to measure topography and altitude and space, a photo of ourselves from long ago is a defining marker in our personal history. These odds and ends of photos that turn up from our past are signposts in some inner landscape against which other insights can be measured and understood. But what, but what?

I don’t much regret that most of my personal photos—there never were very many - have been lost over the years and where, looking back, my life seemed to have veered too far off course, I was often the architect of their demise. The English novelist Lawrence Durrell wrote that we live lives based upon ‘selected fictions’ - where one of the fictions of my personal history became too unpalatable in retrospect, all photographic evidence was consigned to the purgatorial bonfire.

Among the surviving odds and ends, each little freeze-frame moment plucked out of time seems now quite fascinating. To see oneself, or others dear to you, as we actually were, perfectly preserved on film as though cryogenically frozen in 2D, and now a clue to certain existential questions. Tiptoeing among the surviving detritus, tiny windows into the mystery of our personal evolution, I feel like an anthropologist stumbling across the preserved footprints of a dinosaur on a dried up lake bed, marveling at a long ago reality. Flipping through a dog-eared, last surviving family album - already ransacked and depleted by gleeful, shrieking relatives - I ponder over these glimpses of the past, as though by looking deeply enough, or long enough, some understanding that feels so close might emerge off the pages. By arresting time we can also reclaim it, relive it, flesh out each image from the past with all the memories of the mind. Take this image, this memory - my father gazes back at me from a far off time, dressed in his brown corduroys and faded tartan shirt, sitting in his favourite armchair and tamping tobacco into his pipe. My mother, solicitous and kind, brings his slippers, stokes the fire, announces dinner. She allows me to have my pudding first if I promise to later eat all my greens. I promise, and tuck into plum cake and icecream. My sister, sensing parental partiality, kicks me under the table and gloats at my loud ouch. I remember, I remember.

Am I still somehow the same, was everything meant to unfold like this? You flip through the album looking for clues like a Beagle searching for rabbits, searching the bric-a-brac of the past for insight. Had it not been these, would other possible lives have led to the same destination - or to unimaginably different endings? Is our journey forward pluralistic, all the different routes we might have taken inevitably converging at the same end point—or not? I ask because so many of the big things of our life seem founded upon tiny, utterly capricious moments.

Take this photo for example from 1980. As randomly as a feather carried on a breeze, I crossed a city street one day late in that year and wandered into a café in search of a cooling drink - and that was how, in an utterly fortuitous, whimsical moment, I first encountered Sri Chinmoy. That profound and life changing moment seems so capricious. Might the breeze have carried me as easily through another doorway to a different end? I don’t know. But photos give us a clue as to our soul’s intention. And the river, to mix our metaphors a little, always seems to find it’s way to the sea.

Here’s another snap of my father in his last days, lying fully clothed in his bed with a hand-knitted balaclava over his head to keep out the cold - he watches me with lacklustre, faraway eyes and I peer at him through the camera lens, coaxing a tired smile. Days later when the slowing gasps of his breath ended, I sat there with a lifetime of memories and held his hands until the fingers turned cold, hugged his rough face and adjusted the woolen hat as though to warm his cold ears before kind nurses finally shooed me away. Inside the death of anyone you love is all the grief of our race, the timeless sadness that attends the end of life and teaches the beginnings of compassion.

Then to walk aimlessly down hospital corridors where others are weeping at their own private tragedies and consoling each other, escaping out into parklands where schoolboys play cricket under a big blue sky. I like looking at this photo though every time its pathos jolts the heart - yet so much of feeling and love and memory and what it means to be a human being is rediscovered here, or lost if it wasn’t for this little treasure from past times.

Photography, like all art, is essentially autobiographical. We film what we see but we also reveal how we see – the signature and imprint of ourselves is unmistakably there in our themes, our choices, our perceptions. The thankfully vanished albums of my long ago were filled with hunting scenes and wild places – this is what I saw, this in part is what I was. This history has fallen into the sea, replaced by kinder things and new selected fictions. The photos we keep of our history reveal much of ourselves and the things that have most shaped us, touched our hearts. Perhaps our lives are the sum total of all our most intense moments. My private gallimaufry of snaps - permanently disarrayed in random tattered envelopes – reveals an equally tangled mind that recognizes only few compass points and constants: my Guru’s smiling face the lodestar, watching me from a gallery of portraits in my room. And my wife Subarata – six years since she left the world and her presence still fills my life, poignant in photos from childhood to last breath. How well I remember her sudden tears and quick emotions, the sad months of her last illness. Sometimes on lonely nights you wander among these albums and photos of your life as though to reconnect with something lost and not replaced, a void that only God can fill.

It’s odd that photos - images and illusions of life - can help us see life more clearly. Pictures and film lack the third dimension of substance and depth and also the sensual, tactile dimensions such as fragrance and touch, and then life itself. Hold a flower up against the photo of the flower and this is clear. No photo of our dear teacher Sri Chinmoy will ever capture what it is like to stand before him in meditation, any more than the breathtaking panorama of a mountain or a clear night sky can be caught on film – our favourite photos are only those that most approximate.

At times when we are lost to the world or out of sorts we can look at our photos and smile again, haul ourselves back up. For disciples, a treasured photo of their teacher brings out the bright colours in their consciousness and acts as a portal into the secret and sacred universe of the soul, a touchstone to reality.

And in nature photography, a good image lifts us out of a world dulled by urban living and humdrum repetition to bring beauty and surprise, to really see once again. Both art and nature lift us out of the banal where we get caught, into new ways of seeing and realms of fresh beauty and delight.

Jogyata Dallas Auckland - New Zealand

My Grandfather’s Mysterious Visitors

by Kamalika GyörgyjakabWho were they and why did they come?

I was about to write a winter story with lots of snow and even more ice when the message came: our Mahiruha would like some essay on art. OK, I will try. But it is so hard to get rid of this winter, not only the topic of my would-be story (postponed till...), but also of the real one outside. March began with an abundant snowfall. That Friday afternoon I stumbled in knee-deep fresh snow on my two miles long way home from the place where the bus-driver dropped me off saying he simply couldn’t drive any further across this all-white hilly landscape. Two weeks later the waking spring still clenches its teeth and freely allows the wildest winds to ravage all over the villages and fields. The thick overcoats and completely windproof, waterproof jackets are still on us as the days grow longer and the nights become shorter.

It was a similar enduring hopelessness that enveloped us about twenty years ago, too. When will it end finally? And how? Will it end at all? These were the questions we silently asked ourselves day after day back in the communist era in Transylvania. But now, at least I know what I didn’t know at that time: every winter ends. It is a law that cannot be overruled or changed. Not even by the harshest, coarsest, rudest dictators. Neither by their armies, security apparatus, whistle-blowers, squeakers and bootlickers... Every winter ends one day, even the intellects’ and souls’ darkest frozen encagement - time...

Many questions of mine have been answered since those black days in Romania. Except the ones I asked on that winter day: who were those three and how did they come? I am afraid I will never get to know this. If my grandfather was still alive, I could ask him. But chances are high that he wouldn’t know it either. My grandfather was a man of lands, of grains and fields and forests and horses, he hadn’t read too many books until he grew too old to make hay.

He knew however more things than I could find in the books available in our mother tongue at that time. He was already an adolescent when the First World War broke out. Seventy years later, after a mug of beer he would still remember some of the songs sung in another age, in another country, yet in the same village. He grew into a man and he grew old in the same town, but around him the borders changed two times, so he changed passport and nationality, but not mother tongue, neither conscience nor religion. He knew every tree in the forest, every road around the town. He knew every river and brook, every forest pathway. He showed me the places where battles were fought, today’s potato fields watered once upon a time with our forefathers’ blood when Tatars invaded and scorched up our villages, when my ancestors refused the Habsburg rule, when they boldly went against the Austrian-invited allies from the Russian tsar’s army... when they lost all they could lose: their horses, cattle, sons and freedom.

My grandfather remembered the times BEFORE, before the big red revolution sequestrated his hardly earned properties, before his forests became the state-owned hunting grounds of the dictator and the bosom-friends of the latter one, before the “Comrades” forbade our language, before artists emigrated because they no longer could speak up, before food and fuel was rationalised to monthly portions distributed after night-long queues in front of the almost empty shops...

And he spoke to me. That was the root of all problems. He told me the truth. Thus he made me dangerous. By telling me, who he and my other forefathers were, he told me also who I was. That made very clear to me, who and what I was NOT. It was good and also perilous to know this at a time our dictator decided to eradicate 3000 Transylvanian villages for they were useless, obsolete and above all, proved a past that should be erased from history books. By God’s Grace this project could never be realised, but for some years the sword of Damocles kept hanging above our heads.

But long before that, when I was really still a child, we had that long and heavy winter. Towards the end of it, it still looked as if it had just started. In those days, cars were not allowed to circulate at all between November and March, for there was no gasoline. For us kids, this annoyance of our parents meant rather an unbothered roaming in neck-deep snow on the roads themselves after each abundant night-long snowfall. In a March or late February morning like this I ventured on the long and really arduous road to school. One kilometre of stumbling and raising my feet high all the time, covering the last section with totally wet boots and socks. Before leaving I asked my granddad to make me a snowman by the time I got back home. Apart from asking him once to buy me a toy – a painted bird that one could wind up like a clock and that would move around then – I don’t remember asking him anything ever.

I didn’t ask, because although we were sharing the same family house with my father’s parents, my mother was terribly upset with my paternal grandparents. My ever-open compassion-hearted mother, who would always send much-treasured food and delicacies to my poorer schoolmates or to needy neighbours, was very unforgiving whenever it came to her father-in-law. The reason of her staunch, inveterate and unceasing reproachful attitude was that my grandfather had had a hidden amount of money, and when the time came in 1977 he had given it away for a good cause forgetting to allocate a single penny to my parents. Ten thousand Romanian “Lei”-s were a significant sum in the nineteen seventies, more than a yearly salary of an average state-employed accountant like my mother. My parents didn’t have a home of their own. My mother’s parents gave everything they had to my mum, this is how my parents could buy a car. My paternal grandparents gave nothing, but at least they allowed my parents to have two rooms in their house. My mum would have loved to move away from there and live her own life and the mentioned money would have helped my young parents considerably. However, fate compelled my mother to sacrifice her dream of independence. The entire amount went away in an unexpected manner and thus my grandfather bought himself a place fifteen years later on the wall of my room in Budapest. He was the only family member of mine who managed to secure himself (or rather for his photo) a fix spot on a wall decorated by pictures of lotuses, snow-capped mountains, cosmic gods and famous rock climbers. Until the day I moved away from Budapest and stashed all my things in boxes he was hanging there on a framed black and white picture, on horse-back, proud, straight-backed, smiling, as a young father of two small children looking into a brighter future. Little had he known then on September 13, 1940 about what was yet to come. With a radiant face he looked as if he had thought, that yet there was a shortcut to the future.

How did he manage to gain my appreciation? In March 1977 a severe earthquake left the country in rubble. The capital, Bucharest was the most affected, but our town wasn’t spared either. The reconstruction lasted for years. Day after day I would be seeing the ruins of an already run-down fortress and the collapsed dome of our community church, the focal point of the lives of my fellows, the ethnic minority Hungarians of Transylvania. This church was built in the times of the Renaissance, at a place of a yet earlier smaller chapel. The first mention of the settlement dated back to 1321 A.D. and since those early days, whenever an enemy approached the place it was behind the walls of this small fortress that the local population, above all women and children could find shelter. Inside the walls the white church was first a Catholic church and when the waves of Protestantism invaded Transylvania, it was converted for ever. Its gothic shape, pure, ascetically plain white walls are my first memories of talking to God and also, of learning the history of man’s quest for a religion closer to God. These memories include also a hidden side-wall relief work representing the head of some big-eyed humanlike-being with Latin inscriptions underneath, some text from the fifteenth century of which at that time I only understood one single word “Daczo”, a still occurring Hungarian surname, probably that of a noble person or some leader of those bygone times.

After that dream- and wall-shaking, howling night in March 1977 only heaps of broken stones cried into the wind. Obviously, there was no money to start it all over again. The communist state would definitely not afford to sponsor the reconstruction of a minority, state-alien, irredentist, separatist, what worse, RELIGIOUS community building in the middle of the most feared Hungarian enclave of Romania. Out of question. It was German and Dutch volunteers and village communities that came with their big hearts and donations to enable the local priest and my irredentist, grandfather to buy and mix cement and to lay stone upon stone. Over seventy years old, my regime-fiend grandfather would put up his helmet day after day and go along with other volunteers to build the fortress and church back. In addition to that, he dug out that secret money and donated it in its totality for the reconstruction costs.

More than twenty years later, each time I visit my hometown and light-heartedly spend probably much more money there than those long-inflated ten thousand Leis, I walk home over the hill and I see the fortress, the tower of the church and the graveyard nearby. And I know that the earthly rests of my grandfather have a calm, unharassed sleep there. Regardless of my poor mum’s sacrificed freedom, he did the right thing. The church-tower is still standing erect there and can be seen from far.

So, it was this grandfather of mine to whom I said that winter morning: “Please, build a snowman for me by the afternoon.” I thought, I could ask him this favour, after all he had both time and snow beyond measure. Off I went along the almost tunnel-looking pathway to school and then to a school-theatre rehearsal. I reached home sometimes in the late afternoon, but still in daylight, since it was March already. The moment one enters our yard-gate one has an encompassing view of our entire yard, the two flower-gardens on its two sides, the backyard with hens and our dog as well as the barn at the end of it. So, basically I could see in the first second whether my snowman was there or not.

Well, it wasn’t there. What I saw made me run closer. Instead of a snowman, consisting of a huge snowball upon which there would be another, somewhat smaller snowball topped by a yet smaller snowball decorated with coal eyes and carrot nose, as one can expect from any decent snowman, I found there three statues. Aristotle, Socrates and Plato. Or Demosthenes, Cicero and Seneca. Or they could have been Marcus Aurelius, Julius Caesar and Octavian, or Martin Luther, Jean Calvin and Zwingli Ulrich, or why not, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Rafael? Maybe Transylvania’s great governors from the hoary past, Gabor Bethlen, Istvan Bocskai and Ferenc Rakoczi? Or Goethe, Schiller and Rilke, perhaps George Mallory, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, mayhap even Robert Frost, Norman Mailer and Allen Ginsberg... whoever. But definitely not some ordinary people. Three men, three busts on completely smoothed surface, perfect flat pedestals, three noble visages, far-penetrating eyes, bold cheekbones dashing against an unknown medium, all three of them looking into the same direction as they were lining up one next to another.

Who were they and how did they come? What message did they bring along for the ephemeral time between a heavy snowfall and the first spring sunbites? They were there mute, nobly raising their heads, not searching my regard, but rather looking somewhere far behind and above my head, and my grandfather next to them, just finishing with the last touches of his smoothing board. He had been working on my snowmen, his statues since I left in the morning. He used no carrot, no coal, no coloured material, only snow, water and smoothing or plastering tools. He wiped his front and with a smile inaugurated and gave over his artwork to me. Then he went into the house for he had cold. I was staring at the three visitors flabbergasted. Me, the ten year old proud owner of three white Carrara marble statues in the backyard standing with my feet growing roots into the snow beneath...

Then I had to go inside too, the dusk came with chillier breezes. I don’t remember much of that evening. One thing I find still strange though. Although my grandfather had never ever even drawn a sketch, neither my father, nor my mother seemed to be surprised at all, they left the wonder unmarked. Just as if it were so normal that we have three busts of three exceptional fellows in our backyard. Just as if my grandfather was a Rodin in disguise. Well, he wasn’t. He was a man of truth, of lands and forests, of arable fields and hard work, a man of horses and bicycles and also of a good beer sometimes. A man of stonesolid faith. A servant of the church, an expert of grains and herbs and cows... But he was definitely not an artist.

Just two days after that deep snow session my wonderful statues were reduced to small forsaken stubs soaking in icy water. I am the only one to know that on a late winter afternoon Aristotle, Socrates and Plato paid a voluntary visit to my grandfather, or were summoned by him there for my sake. Of course, they could have been Marcus Aurelius, Julius Caesar and Octavian, or Martin Luther, Jean Calvin and Zwingli Ulrich, or why not, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Rafael as well. I don’t remember their faces well enough to compare them now to illustrations representing famous people of the past. But I do remember the smoothness and white nobleness of their faces. They definitely were there, maybe all simply to tell through their short-term snowstatue-carrier that every winter ends one day. That this is a decree which cannot be overruled by dictators and superpowers.

Oh yes, maybe that’s what they had to convey. Or, otherwise, who were they, and why did they come? Who will they visit next?

Kamalika Györgyjakab Hungary

Written to A Muse

by Abhinabha Tangerman"Euterpe glanced her fingers o'er her lute, And lightly waked it to a cheerful strain, Then laid it by, and took the mellow flute, Whose softly flowing warble filled the plain: It was a lay that roused the drooping soul, And bade the tear of sorrow cease to flow" (from "An Ode to Music" by James G. Percival)

She is capricious, fickle, hard to please. She lets you wait for her in desparation for many long hours - and decides not to come. Then the next day she suddenly comes, unexpected, unannounced. Queen of arbitrary appearances, mistress of magical moments, empress of eloquence, embodied by the unseen, subtle thought-wave tickling the brain, instilling in the subtle sense a heightened awareness of the divine reality. She is inspiration. She is the Muse.

If we look her up in a dictionary or an encyclopaedia we come to learn that there were originally nine muses, representing the nine goddesses of arts and science. None other than Zeus was their father. He graced them with melodious names, fitting to their high positions: Calliope, Clio, Erato, Euterpe, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, Terpsichore, Thalia and Urania. A temple erected in their honour was called a 'Mouseion', a name we now give to the venue where the fruits of their inspiration can be found: the museum.

It was not wise to contend with these high-learned gals, as the daughters of king Pierus found out when they entered into a singing competition with the muses and were badly defeated. The muses were not satisfied with victory alone, for legend has it they changed the nine princesses into magpies. The Sirens - mythological creatures with the body of a bird and the head of a woman - whose enchanting and spellbinding songs issued from their rock in the sea sent many a sailor to an early sea-grave, also tried their luck and pitted their musical skill against that of the muses. The Sirens suffered not only defeat, but also the loss of their feathers, as the muses plucked them out to make crowns out of.

The lesson learned is that one should not compete with muses. But instead of competing with them, one can invoke their presence and let their inspiration's flow create works of wonder and beauty, whether in painting, poetry, literature, music or drama. Homer's famous opening lines of the Odyssey still serve as a strong testimony to the idea that the muse of inspiration should be invoked first and foremost in the artist's creative life: "Sing to me, o Muse, of the wise man who traveled far..."

It sometimes makes one wonder why certain periods of history are blessed by an exorbitant amount of creative inspiration and flourish with an abundance of refined and soul-stirring art, whereas other periods seem almost deprived of true artistic beauty and lack a higher inspiration and vision. Could this be explained by the suggestion that the artists of these more prosperous times had more faith in the guidance of the muse and consciously or unconsciously invoked her presence? Or by the assumption that the muse herself was more active in these periods, scattering her seeds of inspiration freely about, and more withdrawn in others, retired behind the walls of her castle on the Olympus, unseen and unheard by mortal eyes and ears? Do we invent the gods or do the gods invent us? An eternal question to which no clear-cut answer has been provided. Perhaps it is a little of both.

But enough 'musing' on her rich tradition and past, for the past - as they say - is dust. What you and I want to know is how we can successfully invoke the muse here and now; how we can tempt or persuade her to descend from her pink cloud and mingle with our crying efforts, so that we can create something beautiful, something worthwhile, lasting and satisfying. For too often have we endured her cold silence and the empty hours of her absence. Too often were we to rely on our own limited faculties, forced to be satisfied with mediocrity. Yet when she finally shows herself, she leaves too early, before her work is properly done and we are left with two sublime lines of poetry or a few inspired brush strokes while the rest of the painting and poem are doomed to the well-meaning sweat of our human brow, missing their promising claims to immortality.

So how can we capture the muse permanently and bind her to us irrevocably? When looking at and observing the lives of the great Masters of art, there seems to be only one answer: one needs to practise diligently, ceaselessly and untiringly. Practise makes perfect, as the old adage goes. It seems a terrible cliché, but then again, what is a cliché? A cliché is nothing other than a core truth too often heard and too little practised. Hence it loses its hidden truth-power, becomes tedious and from tediousness quickly grows into a despised cliché. But its essence is truth, changeless and eternal. Practice makes perfect. There you have it.

Van Gogh practised, Vermeer practised, Rembrandt practised. Shakespeare practised, Milton practised, Whitman practised. They all worked hard and gained the muse's blessings. No magical formulas then, no secret mantras or ancient rites to win the muse's favour? No other way to her Olympian castle but through toil and labour? Perhaps not.

Yet there are hopeful words of wisdom for those who long to be in her close company. For there might be another way open to us, a hidden path, a shortcut to the muse's dwelling. This shortcut is revealed by someone who seems an intimate friend of the muse, having written thousands of books and poems, created over a hundred thousand paintings and composed many thousands of songs. Someone whose artistic fruits are aglow with a special, uplifting and otherworldly light and beauty: spiritual teacher Sri Chinmoy. Sri Chinmoy has encouraging words for the budding artist:

"Right now you are at the mercy of inspiration. If you don't have any inspiration you cannot write anything. ... But if we have become very highly developed seekers, then we acquire the capacity to compel the bird of inspiration to stay with us for as long as we want. Anyone can develop that capacity, provided he prays to God, meditates on God and devotes himself to the inner life." (from: "Sri Chinmoy Speaks, part 9")

In the end the answer is a calling to our deepest soul: to connect ourselves with the very Source of creation deep within us and establish a vibrant link to its fountainheads of ever-flowing inspiration. A lofty task indeed. Let us try!

Abhinabha Tangerman The Hague - The Netherlands

Image: Detail from "The Allegory of Painting", The Muse Clio - by Johannes Vermeer

Paris, Je t'aime!

by Sharani RobinsSuch a francophile in my younger days, at long last I visit France. I went to Paris for several days with the Sri Chinmoy Centre and it fulfilled my dreams and expectations beyond my imagination! I felt and appreciated that "Je ne sais quoi!" in every aspect of the culture. I have never seen such density of beauty in every detail, every building, every direction you look. Hemingway was right when he said in his book "A Moveable Feast" that once you experience Paris it will stay inside you for the rest of your life.

Contrary to the stereotype, we also found people to be most helpful and not put off by our being Americans speaking English. After we came down the hill from Sacre Coeur on a vertical tram, we needed to find a subway station to get back to our hotel near the Montparnasse train station. We asked a lady "metro?" and it was pretty funny. She looked at us rather baffled as we said metro about a half dozen times. Suddenly a light bulb went off in her eyes and she said, "Ah, metro!" You see we were pronouncing it with emphasis on the first syllable especially the first two letters like the word let, pet or set. She pronounced it with a flourish of a rolled r and an emphasis and elongation of the second syllable that made me think of the word Bordeaux with a nicely rolled r.

As soon as she realized what we needed, she very kindly explained where the nearest station was (I forget but it was probably a combination of simple English and French for her answer to us). I understand some French so it all started to blur together for me. I knew I was like a duck to water when my American companion answered a question of mine with the word no and in my head I saw the word spelled as no with the n on the end of it (French spelling non). All superlatives have long since been exhausted over the years in regards to Paris so rather than repeat them yet again I settled on the metaphor of Paris being a ballet dancer. I was a ballet fiend as a kid and lived, ate and breathed ballet dancing. As I got older, the ballet school I studied at took it all pretty seriously and I had to make a decision to either dive in further or according to their preference just quit. Excelling in school meant a lot to me too at that time so I ended up quitting my study of ballet. Plie, releve, grand jete et change! Au revoir!

Paris is like a ballet dancer because every little movement in ballet has to embody grace and beauty. The act of simply walking across the floor or raising your arms has to be accomplished with intense grace, style and beauty. In fact, people used to kid me because I couldn't walk with a normal gait outside of class - they said I always seemed to prance with a little spring to the feet when just walking. This my friends is a telltale sign of a ballet dancer.

So in every little detail Paris contains that same kind of grace and beauty. Whether the food, the art, the architecture, the clothing/fashion, all is permeated with an underlying and delicate beauty. Like a ballet dancer crossing the floor even as an art form, so too Paris manages this in its mere existence. I find it more than easy to see why so many writers, artists and intellectuals from America became expatriates in Paris in years gone by. Oh to be a fly on the wall at Shakespeare & Co. and to rub elbows with Gertrude Stein and others.

Finally, can you imagine me saying all this and I didn't even go to the Louvre or the Orsay Impressionist museum? We only made it to one museum - the Rodin museum but that alone was overpowering in its impact. I think I could go back to that museum countless times and still receive something from Rodin's sculptures. It wasn't really spring yet in Paris but it was in the Rodin museum gardens that I found one lone flowering tree to frame Les Invalides (where Napoleon's tomb is) in the background of the picture. Heaven, I was in camera heaven!

The world around me seemed so drab after I got back that Mother Nature had to present a spectacle of light and clouds and rain while coming home from work. As if a line was drawn in the sand (sky), the area that I was driving out of was dark, dark purple/black and stormy with steady rain. Ahead of me on the other side of the line in the sky it was mostly clear and the sun was emerging from a few clouds as it set. As it descended towards the horizon , dazzling columns of light radiated up to the sky right through the clouds.

Because it was raining where I was at and the sun was up ahead, I put on my rainbow chasing cap and did eventually see and photograph a partial rainbow once I got to Providence. Rainbows have brought me back to the charm of coastal and somewhat rural New England. Bloom where you're planted they always say. But guaranteed to bloom for sure if you're ever planted in Paris. My photos of the trip can be viewed at my "American in Paris" album.

Sharani Robins Rhode Island - USA

Reflections on Picasso and Masaccio

by Ed SilvertonA few years ago I had the good fortune to visit Barcelona for a week and feast my eyes and heart on that city's rich visual heritage. During this time I visited the Picasso museum, which chronicles his life by displaying drawings, paintings and sculptures selected from his prolific output. It does appear true that in his youth he could draw as well as many a master before him. `Conventional' in execution, his early drawings are testament to his huge talent and skill, which he used in various ways throughout his career.

As Picasso went through life, he seemed to be searching for a way to draw like a child again and produce works that had the simplicity and spontaneous magic of a child's creation. However, there is a period in his life around 1922-23 when he produced the works that I love the most. I have a card entitled `Mother and Child', a reproduction of a Picasso whose original is currently in the Baltimore Museum of Art that is so beautiful it almost makes me weep to see it. It shows two figures so utterly at ease with each other, in a soft and tender exchange that it conveys perfection in contentment and mutual self-absorption.

Softness and tenderness are two qualities that actually rarely appeal to me in the art world, which is funny as these heart qualities often come to the fore when I'm trying to do something myself. Maybe it's because so much of what is in the art- world does not appeal to me that I welcome the `justice-light' aspect of powerful art. I imagine it cutting through the dross of mediocrity and soppy sentimentality that is often seen in works alluding to something higher or deeper but lacking any solid foundation. How can I say this? Well I can only go on my inner feeling when I look at art and if a piece moves me then I am grateful and encouraged, and if it doesn't move me, then I move on.

I would like to recommend Masaccio (1401-1428) to anyone that has not heard of him. He is regarded as the first great painter of the Italian Renaissance and greatly influenced those who came after him. I love his work not because of his ground-breaking use of perspective, but for the power and emotion that underpin them. Two of his pictures that move me most profoundly are frescoes painted for the Brancacci Chapel, Italy. They are: `Saint Peter Baptizing' and `The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise'. These contain a volcanic energy that simmers and boils, barely contained within the painted surface of the works. It came as no surprise to me that he was a deeply spiritual person and his religious works reflect this. In contrast, many of those who came after him produced work that was technically more advanced and refined but lacking spiritual depth. Michelangelo had power, Raphael had refinement, Leonardo had vision, but Masaccio had Purity and for me, Purity wins

Ed Silverton Bristol - England

Image: "Mother and Child" by Pablo Picasso, 1922, (Baltimore Museum of Art)

The 'Way' Of Photography

by Pavitrata TaylorThe editor asked Mr. Pavitrata Taylor, a seasoned, expert photographer, to share his views about the philosophical aspects of photography. The questions and Pavitrata's answers follow.

Is there a ‘Way’ of photography? Photography is amorphous; it is all things to all people. For me, photography is a celebration of life. Some would say, ‘That guy has too much time on his hands.’ However, you can only start with yourself, and reveal your own hopes and aspirations through your art. If there is such a thing as a ‘Way’ in photography, I would say it is defined in the phrase: ‘To be a pilgrim through the visual world’. That is how my good friend Uranta puts it. I like that, I like it a lot. It implies an integrity of outlook, a dignity and depth of purpose that I believe should always be invested in one’s creative perceptions. I also like it because it goes beyond photography; you don’t have to know anything about cameras to be that pilgrim. However, photography can certainly help in focusing one’s awareness, to develop an inner eye through which the beauty of the seen world is transposed and revealed.

Photography is at once practical and mysterious. See something that interests you. Click. Take the picture. It can be as simple and perfectly workable as that. However, if you aspire to remain in a visually perceptive consciousness, things happen on another level; you start to understand Henri Cartier-Bresson’s evocative quote: ‘Every circumstance has its defining moment; the good photographer will be aware of it before it happens.’ It sounds strange - pretentious even - but good photographs do seem to quietly present themselves. In certain situations one can just feel there is a fine photograph nearby. Sometimes the backdrop is there, but an element is missing - you don’t know what it is yet, but often if you simply wait, something will happen that will complete your untaken photo. Eyes need a distance, but they also need a place to rest, a touchstone that draws the photo together or complements the whole; perhaps someone moving through an otherwise still place, or a small and bright object in a vast space, or maybe a point of stillness in a busy scene.

On the other hand the heart will have its way - the concept of the well-composed photo may be confounded by our feelings about people, places, and events. We would all rather have an ordinary photo of someone or something special to us than an amazing photo of something or someone we have no feeling for. My Scottish gran was an exceptional person with rare qualities. My favorite photo of her is a small, faded, tattered snapshot I took when I was sixteen - it has no artistic merit whatsoever but remains one of my favorite photos.

Which is better- digital or film? For convenience, editing, speed, control, web, email etc, the answer has to be digital. For quality, color and ‘presence’, then I would say film. In my experience, a good negative scanner and a well-exposed negative, with careful post-processing, will give better results than digital. It’s not all about resolution; it’s also about quality of color and subtleties of tone. Digital images often seem to have an inherent ‘flat’ feeling to them. The best quality of all is from a projected slide, it really is the closest you can get to the original view. However, the ‘original view’ may not be what you want.

The other problem with digital photography relates to some of the points mentioned in the answer to the first question. Rather than honing one’s visual and technical skills to the point where the photo is realized at its most perfect moment, with hundreds of images now available on modern memory cards, there is a tendency to just take lots of photos. We all do it, and it doesn’t make us better photographers, it just tends to make us more obtrusive and intrusive. At grand events we go into overdrive, snapping and chimping - even taking photos just to check the exposure level! I am the worst culprit here, and ‘fess up to the fact. The only plea I have in my defense is that I refuse to put any camera into drive mode, whereby one holds the shutter and it just keeps taking pictures continuously. I salvage a little dignity by at least taking each photo individually! It’s surprising how much more careful and considered our digital photographs become when we only have a few possible images left on the memory card! Then we frantically start chimping to see what we can delete to make more space so we can just go into digital overdrive again! What a game! Digiots, aren’t we just? Digital idiots! You have every right to laugh at us! Until you get your first digital camera that is, and you become a chimper yourself!

On the plus side, digital cameras do make the process more sociable - the joy of sharing with others the photo just taken. It may be also be that people are relying on you to take a good photo of an unrepeatable event, and in that case the digital aspect helps in ensuring you don’t let people down. The control aspect is important. Anyone who has had their negatives lost or damaged by a lab will appreciate the relative security of the digital image. The other great thing about digital images is that they can be copied without loss of quality. You could, on the other hand, see this as a curse: the uniqueness of a single negative or slide is lost, and that which was once totally original has become endlessly duplicated, each replication identical to the first.

What makes a great photographer great? I read something today that made me chuckle. ‘A great photographer is someone who doesn’t show you their dud photos.’ There is truth in that. Photography, being so easy and accessible, is very enchanting. But after a few years you look back on your previous output and wince. A while ago I went through photos from my first few years with a camera. While patiently looking through several thousand slides, prints and negatives, deludedly thinking, ‘Ah, let me once again peruse these pearls,' I came up with only thirty competent photos, of which just five were good enough to print! In the end only one of these got enlarged, which is the picture of a clown waiting for a bus. I do even have some ‘issues’ with that one picture, but it’ll have to do, as they say.

My photography got a lot better once I started working in black and white. I took far fewer photos, knowing each one required darkroom time - but the ones I did take had a considered and thoughtful feeling about them, helped by the fact that I was able to work on them in the darkroom to get what I wanted. I don’t actually think you have to go through all this bupkas to produce great photographs as though it is some arcane art form for which you have to suffer! I just try and make up, with patience and determination, what I lack in talent!

I would say it is difficult to produce consistently good photographs without a thorough technical knowledge of your camera. You also need an ongoing awareness of composition, tone, form, and the way light works. To get the photo you want time after time, you need to be able to visualize the way you’d like it to ultimately look before you press the shutter. The photo you really want may be very different to what is actually there. It is that ability to take what you see and change it into what you can imagine that defines the photographer as an artist: the sum of experience condensed into a heartbeat. For all that, whatever you do to the image afterwards will not turn a poor photo into a good one.

For any serious photographer then, I would say that the original image from the camera is just the starting point. The darkroom or the editing program then become the tools whereby you actually begin to resolve this image with your original vision for the photograph. Whatever way you work, in the end your picture is just a set of shapes and colors on paper or screen. First of all these have to work together as an abstract arrangement. Underneath the illusion of the subject matter of great photographs or paintings you will invariably find a coherent balance where all the elements of form, tone, and light come together in harmony. I guess it’s a classic idea of visual aesthetics, and if you aspire to it your photos can only improve.

For all that, there are photographs that are haphazard - where the subject matter is so powerful in its immediacy that it renders irrelevant all the rules about what is or isn’t a good photo. One of the reasons that I like Henri-Cartier-Bresson so much is that he had the rare ability to combine both aspects; to capture a seemingly ordinary and random event in an exquisitely balanced and resolved way. His work shows a real mastery of visual synchronicity. It also reveals that in some way perfection can be found in the simple events of everyday life, if you know how to see them. To ‘see’ like that you really have to be fully alive in each moment. That is the exhilaration, the joy of photography - and for me that is where photography and spirituality meet.

Pavitrata Taylor London - England

The Universal Language

by Barney McBrydeIt is often said that the arts form an international language - a language that transcends the spoken languages of humanity, that unites where there can so easily be division, that communicates fluently where there can so easily be misunderstanding

* * *

There are those who go to art school chiefly to drink red wine and air their pretensions at parties. Certainly I did both as much possible, but I also applied myself strenuously and with dedication to the work - I was going to make the most of my time there.

We did little purely academic work - mostly we rolled up our sleeves and made art - but once a week we had an art history lesson and for that I think in the course of a year we had to write two essays. One I wrote about the Fauves, the Nabis, ‘Le Talisman’ painted on a cigar box and all that. The other I wrote about Alphons Mucha - the great Czech artist, the man who more-or-less invented art nouveau.

Writing that essay introduced me to an artist who impressed me hugely and who was to influence my own art to a large degree in future years.

Eight years after writing that essay I found myself standing on a pavement in Prague, my finger hovering over a doorbell above which in neat script was written the, to me, improbable name - ‘Mucha’.

When I plucked up courage to push that bell, an elderly woman put her head out an upstairs window and we shouted at each other for a while before she disappeared. Fortunately she reappeared at the door and even more fortunately she spoke impeccable English which meant she more-or-less understood when I explained that my brother was married to a woman whose grandmother was her cousin. This was a fact that I had only recently learned.

Admittedly it wasn’t a great link, but, since she herself was Alphons Mucha’s daughter-in-law, it did mean that Alphons Mucha’s son’s wife’s mother’s sister’s great-grand-daughter’s husband’s brother was. . . me - could I come in and take a look around?

It wasn’t actually the studio Mucha had worked in - that had been commandeered by the communists for an embassy - but it did contain many of his possessions - his easels, his brushes, his furniture, his stuffed owls - and a great deal of his art. For me to be guided by this genteel old woman around the house was an impossibly special event.

Hanging on the wall amongst the other art were several paintings of a small boy - his round, angelic little face framed with golden curls. My guide gave him a fond, octogenarian smile and said, ‘. . . and this is my husband.’

Art not only speaks across space, across cultures and languages, it speaks across time. It is a time machine by which the past may communicate with the present. By means of these daubings on canvas, Alphons Mucha could communicate to me a hundred years in the future his ideas, his feelings, his dreams, his aspirations; could move and provoke and influence me and my view of the world. Here in this room he could present to this woman the man that she had loved, borne a son with and buried - and introduce him to her as he had been long before she even met him.

A few days later I was on a bus wending its way deep into the Moravian countryside.

That road to Moravsky Krumlov was a road to another world - narrow, winding, lined with trees and little allotments and small orchards and green meadows and wayside shrines to Christ and His mum and Saint John Nepomuk. We passed through villages with unpaved roads and a drain down the middle of the main road.

The village of Moravsky Krumlov was a little more substantial. It was here that Alphon Mucha’s much-ignored magnum opus, his series of twelve enormous paintings of Slavic history - ‘the Epic of the Slav People’ - was housed in a large and dishevelled chateau on the outskirts of the village. As it said on my 40Kc ticket to get into the chateau - ‘From 1963 the cycle, thanks to the town of Moravsky Krumlov, has been installing on local castle. Extraordinary interpretation of paintings and their eventful destiny attract notice of the present visitors.”

In Moravsky Krumlov nobody spoke English. I mimed my way into getting a room at the Hotel Jednota and some food at the shop.

When I arrived at the chateau, there was a guide showing a bus-load of school children around. I was touched to see them sit on the floor before a vast painting as an old lady talked so gently to them of the epic past of their own nation.

Those of us who suffered under the disability of being foreigners had to make do with a few photocopied sheets of paper as our guide. They were in French, German or English and explained some things . . . but made others more mysterious with their peculiar style:

The painting of the early days of the Slavs was described - ‘They were peasants than hunters. Thus gaining some property they were attractive for nomadic tribes from the east and the regardless Goths from the west’; St Cyril was described notably as protecting the Slavs from the ‘violet Christianisation carried out by the Germans’; the Painting of Tsar Simeon of Bulgaria was noted for the technique used - ‘the whole picture is painted in Byzantine many coloured and made-up way’; there were even some moral exhortations - ‘Peter Chelcicky advances him repressed his anger and blames him for not to repay evil for evil, because if he resists the evil, the evil is multiplied in the world only.’ Sound advice . . . perhaps.

Language divided us but art spoke across the divide.

In the end one needed no written explanation. The power of the art spoke direct to the eyes and heart of the viewer, sweeping one up in the artist’s broad vision of life.

Neville Chamberlain - British prime minister - said of Czechoslovakia before the Second World War that it was a far away country full of people of whom we know nothing. Wandering, a mute alien, around the streets and fields of Moravsky Krumlov, or deciphering the halting attempt at communication across a language barrier in that art catalogue, I often felt he was actually right. But the art - it spoke with the eloquence and passion of a native speaker. Words were finally superfluous. The language of art was doing its job.

Barney McBryde Auckland - New Zealand

Image: "After the Battle of Vitkov 1420" by Alphons Mucha

Memories Of Collecting

by Mahiruha KleinIt’s really hard for me to let go of objects that have sentimental value for me. Unfortunately, being a sentimental slob, that encompasses just about every damn thing I own!

Oh no, I can’t let go of this copy of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy! My uncle bought it for me after I came in second at the debate-and-speech tournament in Yardley (fifteen years ago!). Or- true, this potted plant has been dead for a year but it lasted longer than all the other ones I forgot to water!

Am I alone in being a maniacal collector of things I don’t really want? Do other people who don’t own record players belong to LP clubs?

I guess I can salvage some dignity in that I have rather high-brow tastes in what I collect. Six copies of the complete works of William Shakespeare, for example. And, incredibly enough, they’re all the same. But the covers are different and I guess that justifies my expenditure.

When I go to Europe to see my sister, I bring back lots of Euros. I keep them in a drawer and I go through them every once in a while, admiring the shiny coins. They are of course useless in America, but sometimes I go to my local health food store and ask them if I can buy my granola in Euros. Usually they think it’s funny.

My mother, like me, was a collector. An amateur art dealer, she collected mostly neo-Expressionist pieces. I dislike most modern art movements intensely and was happy when people would come to our in-house gallery and take away the hideous paintings and give us money for them. She promised me she wouldn’t display any art in my room and that made me happy!

I don’t have a lot of things to remember my mom by. I have a few photographs of my bar mitzvah, where she’s smiling at me, with her hands on my shoulders. I also have a big portrait of her, painted when she was just a little girl. It’s a painting of a small, quiet child with beautiful green eyes. I keep it in my closet and look at it from time to time. Perhaps I will send it to my sister, and I will just keep the photographs because they give me more joy.

I’m happy I don’t really hoard art, at least. That gives me lots of freedom to go to the art museum, to see really great works of art. At its best, it teaches us not only how to see, but also what happiness and fulfillment really mean. Perhaps that’s why I love and admire Cezanne and Gaugin so much. Not being trained in art history, I cannot give any weighty or considered reasons as to why I feel so drawn to these artists’ works. I can only say that Cezanne imbued his paintings with the most remarkable details. His work is always endlessly interesting and captivating. There is always more to see.

Gaugin inspires me because he traveled all the way to Tahiti for the sake of his artistic journey. Now that’s commitment! And his paintings are so different from anything else; so mysterious and otherworldly and yet so solidly grounded in the technique of the Old Masters that I never get tired of them.

Maybe art is about acceptance. Life can be tragic, confusing and unsettling. Art is an opportunity for us to face the difficulties of life and to make sense out of them. A constructive response to suffering, we create a garden out of the debris, a rose rising up from the dirt. We can reformat or reformulate our troubles to discover Cezanne’s skies and Gaugin’s beaches inside them. We can transcend ourselves, and I think our journey towards perfection is the most beautiful art of all.

Mahiruha Klein Philadelphia - USA

Image: "Mont Sainte Victoire" by Cezanne, 1885-1887

Our members

Stories

First-hand experiences of meditation and spirituality.

A 40-Year Blessing

Sarama Minoli New York, United States

Running for Peace

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Bhutan, A Country Less Travelled...

Ambarish Keenan Dublin, Ireland

How my spiritual search led me to Sri Chinmoy

Vidura Groulx Montreal, Canada

How I learned from Sri Chinmoy

Pradhan Balter Chicago, United States

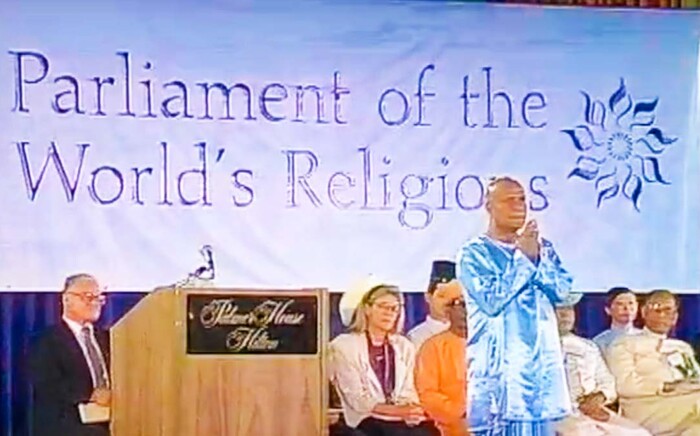

Sri Chinmoy's opening meditation at the Parliament of World Religions

Pradhan Balter Chicago, United States

I was what you call a classic unconscious seeker

Rupantar LaRusso New York, United States

“Where there is heart, always there is a way.”

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

My inner calling

Purnakama Rajna Winnipeg, Canada

The Ever-Transcending Goal

Preetidutta Thorpe Auckland, New Zealand

In the Right Place, At the Right Time

Eshana Gadjanski Novi Sad, Serbia

President Gorbachev: a special soul brought down for a special reason

Mridanga Spencer Ipswich, United Kingdom

Muhammad Ali: I was expecting a monster, but I found a lamb

Sevananda Padilla San Juan, Puerto RicoSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

Life in a spiritual workplace

Pranlobha Kalagian Seattle, United States

Experiences of meditation

Preetidutta Thorpe Auckland, New Zealand

My daily spiritual practises

Muslim Badami Auckland, New Zealand

Winning the Swiss Alpine Marathon

Vajin Armstrong Auckland, New Zealand

Running the world's longest race

Jayasalini Abramovskikh Moscow, Russia

Where the finite connects to the Infinite

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Running for peace in the South Pacific

Nirbhasa Magee Dublin, Ireland

Except where explicitly stated otherwise, the contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. read more »

SriChinmoyCentre.org is a Vasudeva Server project.