Inspiration-Letters 9

Book Reviews

Dear Reader,

This issue is devoted to book reviews, the most essential form of literary criticism. When we pick up a new book, often many questions nag at the back of our mind: Is this a good book or a bad book? Should I read it? Will other people enjoy reading it, or will they think me a fool for reading this and enjoying it? There are so many reasons why we turn to reviewers, critics and scholars to settle our opinions for us about life and the world.

This issue is devoted to book reviews, the most essential form of literary criticism. When we pick up a new book, often many questions nag at the back of our mind: Is this a good book or a bad book? Should I read it? Will other people enjoy reading it, or will they think me a fool for reading this and enjoying it? There are so many reasons why we turn to reviewers, critics and scholars to settle our opinions for us about life and the world.

When I go out to eat in nice restaurants, I ask the waiter to recommend to me the four most delicious dishes. Then I scrupulously avoid ordering any of them. I am myself a waiter and I recommend people the tastiest dishes. But when I dine out, I am invariably disappointed when I order along the lines of the waiter’s suggestions. I almost get the feeling they recommend food that I should like, because it’s expensive or fashionable, rather than on how it tastes.

And how should a book taste? Or sound? I was listening to Beethoven’s last string quartet (and last composition), Opus 135 in F major, on the radio one night in the kitchen. They were playing the next to the last movement, a long, beautiful piece. One of my cousins entered the room and told me that the music had a deep blue color.

Speaking of books with a ‘blue’ theme, I have read Moby Dick, by Herman Melville, many times. The book is mantric and long and strange and wonderful. I like the opening scene in the novel. The narrator describes how, at the end of the workweek on late Friday afternoons, Manhattan shipyard workers, accountants, servants and schoolteachers used to congregate by the water, and just look at the vast ocean for hours and hours- how people are invariably drawn towards water, like iron filings to magnets. And I like how the author sells everything he has for the chance to be a member of a whaling party. He doesn’t want to see the world, or get rich through being a whaler. He simply wants to live and work in the water. And that’s what the spiritual life means, to put aside everything you know to be immersed in the beauty and the fragrance of the unknown.

The book that had the biggest influence on me is Beyond Within, Sri Chinmoy. It is one of those books that’s simple and clear and deep. Interestingly I would not have been so moved by Sri Chinmoy’s beautiful prose and simple but haunting ideas if I hadn’t at that time been terribly sad at not having gotten into the college of my choice. In that awkward moment of self-doubt, I found this book to be so uplifting. Beyond Within deals with how to have a connection with God while fulfilling all of our day-to-day obligations.

We Inspiration-Letters-writers are extremely grateful to be able to share with you our thoughts and ideas on the art of book reviewing. I hope these articles inspire you to revisit your favorite books with a fresh perspective.

Mahiruha Klein Editor

Title photograph: Pavitrata Taylor

Musashi by Eiji Yoshikawa

Sumangali MorhallThis is ostensibly a book of swordsmanship, and includes its share of martial combat, but that element is neither gratuitous nor glamourised – it serves to support rather than blemish the story’s purpose. Musashi transforms himself from a brute and selfish thug, to a hero of great depth and honour. Through the teachings of Takuan Soho and through his own self-discipline and one-pointedness, he transcends his natural capacities in the pursuit of his life’s mission.

Although Musashi was the maven of martial arts in his time, Yoshikawa portrays his many human aspects so as to bring his character into real and living relief – not a mere legend, but a man struggling with failings and weaknesses, in whom one can surely glimpse one’s own self. Never coldly observing from outside any character, Yoshikawa becomes the character and writes straight from that beating heart, or racing mind, or pulsing body. Each character has its place in the tale and its own unique lesson for the reader.

Yoshikawa’s research is such that every angle of the culture and every level of the social hierarchy is revealed in robust detail. The writing is complete and completely satisfying, pristine and elegant. No single word is superfluous, yet no detail is trivial enough for exclusion. One may well take any sentence from any of the 970 pages and let it stand as a striking, intriguing work of prose.

More graceful than grisly, this is the account by one master of another master's life. Whether you choose to read this book for its historical content, its study of martial arts, its celebration of Japanese culture, its portrayal of human transcendence, or simply as a heroic piece of writing, you will not be disappointed.

Sumangali Morhall York, England

Grace by Sri Chinmoy

Jogyata DallasI have been reading Sri Chinmoy’s little book called Grace, one of a mini-quartet that also features Love, Compassion and Forgiveness. Head-nodding vigorously at the lovely insights and illumining explanations packed onto every page. Looking back over a personal life that has included many wrong turnings and foolishness I can see quite clearly the unmistakable signature of grace, bucket loads of it, taking me firmly by the hand and turning me away from both the folly of an empty career or a hideaway life of seclusion to gift instead a spiritual life — or attempts at this — with a wonderful living master.

I first stumbled across evidence of grace in my life about ten years before it set me on my present course – I was a safari guide and one winter my employer flew me in a little two-seater plane into the remote heart of a wintering mountain range in New Zealand. Looking at deer and trout populations for summer clients to harass.

“Did I ever tell you the one about the Scotsman who lost his kilt?” asks Ken the laid-back bush pilot, trawling through an endless anthology of dubious jokes. “No”, I say, inwardly sighing, “No I don’t believe I’ve heard that one.” Ken is about to launch into another salacious narrative when there’s a sudden blast of static on the radio, a voice coming into the cockpit, weather warning, mountain winds and cloud coming in up ahead, get in and out fast. The tiny Cessna skims over treetops, a saddle between rising mountains towering on either side, drops down into the valley. Ahead the grey shingled braids of the Ngaruro River, the northern catchment snaking among manuka and tussock before disappearing at the top end of the valley into a wall of beech forest. “Bandit at nine o’clock,” says Ken, and sure enough, down below out the left cockpit window a young red deer stag is skedaddling across the shallow water, geysers of spray, scrambling up an embankment and swerving through scrub for the cover of trees. Ken dipping one wing in mock pursuit, a strafing run…

Grace is a lovely book. It describes the love and compassion of God responding to personal effort and falling unconditionally like rain on agnostic and believer alike. Personal effort, magnet-like, always attracts grace – and grace increases our hunger, deepens our meditation, clears away the blocks and obstacles to expedite our progress.

For most of us the concept of grace with its assumption of the existence of God has little reality. Either we do not believe in God or, overly conscious of our blemishes and wrongdoings, we cannot believe that a God could love us constantly and unconditionally. But the opposite is true and Sri Chinmoy writes: “Personal effort cannot live by itself even for a minute, because its inner nourishment is the Grace from Above… God’s Grace is responsible for everything. This moment it is using our hands, next minute it is using our legs, next moment it is using our mind, next moment our breath or our heart.”

Grace is one of the elusive, powerful mysteries of God’s love, the key to that great alchemy that transforms ignorance into knowledge, disbelief into devotion, seeker into saint.

Ken Dooley, cool as a cucumber, shot down eleven times in Vietnam as a chopper pilot, sole survivor twice – charmed life or jinxed? – sidestalls down to lose altitude quickly, hard banking in the narrow valley, the small plane turning on a dime, lurching and jumpy in the wind then we’re lining up for a rough touchdown on the banana shaped makeshift runway, hand grubbered on a river terrace out of yellow tussock, pumaceous earth. A jarring impact, a hooter alarm sounds briefly in the cabin, we’re bouncing ten feet up again, Ken whooping like a rodeo bull rider, then down and hard braking, charging left around the curving strip and every rivet in the fuselage groaning. “Bingo!” says Ken, flashing rows of expensive smiling teeth. Now we’re unloading gear, two weeks food, then Ken’s back in the pilot seat shouting wisecracks – “Back in a month or two if I remember, sure hope I can find this place again.” Grins, thumbs up, then he’s off in a roar of throttled engine, dust and flying leaves, climbing up and banking in front of the mountain wall, turning down the valley for another run to gain altitude, waggling his wings overhead before clearing the saddle and gone, a tiny droning fly.

Belief or disbelief in grace does not alter its reality any more than our expectation of a sunny day might stop a sudden downpour — and an open mind/open heart will gradually reveal its existence. As we become more conscious of grace in our life, a direct personal experience, our faith and surrender and our feeling of being God’s child deepen. Anxiety disappears, love and patience come, everything is being taken care of by God the infinitely loving parent. This is not a dogma or a philosophy or an idea but Reality. You know it, live it, feel it.

Sri Chinmoy writes: “God’s greatest adamantine Power is His Grace. The moment God uses His Grace for an individual, He offers His very Life-Breath to the seeker. If we approach God with the heart and the soul there can be no dryness, only a constant shower of love and Grace.”

I have broken a cardinal rule of the mountains. Last night, one hour before light drained out of the valley I went up through thick beech forest behind my camp, left my small daypack with emergency supplies behind. A sika stag was roaring up on the ridge and I sneaked closer for a look, excited, though knowing I was on the edge of darkness. When it slipped down the side into the catchment of another river, I followed. Big mistake. Hurrying back to beat a black night in which you cannot see or move, I took the wrong spur, ended up in a streambed taking me away from my camp, a different river system. No food, matches or rifle and thirteen hours of darkness till daybreak. Rain falling. Have to find a way to stay warm, to last the night. No rock face for shelter, no fallen trees or caves; cutting long fronds of mamaku fern with my sheath knife and building a flimsy lean-to, keep out the worst of the rain. In the morning after a sleepless freezing night, feeling half dead with exhaustion. And now a primal struggle to survive.

Many people talk of a relentless causality that governs our lives. From the alignment of planets astrologers also make charts that predict what will happen. But grace can nullify everything. Sri Chinmoy reminds us that “there is a world which is infinitely higher than the planets. From there we can easily create, and we can also delete anything in our fate… then we can add something new. Your fate can also be adjusted by the Grace of the Supreme.”

A pea-soup fog blankets the mountains, snowdrifts fill the creek sidings, zero visibility but have to keep moving, backtracking to stay warm. Snatching mouthfuls of water, the bitter stringy pulp of punga fronds for energy, keeping at bay the constant menace of death by cold. Forcing myself not to panic, to stay calm – an errant step here, a broken ankle or bad fall would be the end. Nobody would ever find you. Man down.

Grace especially permeates our being when we are in the field of aspiration, even to the point of nullifying or changing our karma. Sri Chinmoy uses the analogy of a child who does something wrong then runs to the father to avoid the consequences. The father has compassion for the child. He knows the child has done something wrong but safeguards the child from the consequences.

Comments Sri Chinmoy: “In the case of an ordinary, unaspiring person, karmic dispensation is unavoidable, inevitable. The law of karma is always binding: like a snake it will coil around him. He has to pay the toll, the tax; the law of karma is merciless. But again, there is something called divine Grace. If I shed bitter tears and pray for forgiveness, then naturally God’s compassion will dawn on me. Divine grace plays the role of the father. If the father wants to protect the son, he can.”

Day three. Prospects are bleak – I need a miracle. Winter’s relentless rain and snow, lack of food, bitter cold, wet clothes freezing on my skin have reduced me to a stumble. I have to sit a lot. Mind, ego, self have all gone, worn away. This close to death you don’t care about yourself anymore – glad to get it over with. But sad all the way through for my family, especially my parents. Here at the end, agnosticism also falls away, the proud and shallow constructs of the mind tumbling like a house of cards. I’m starting to pray, plea bargain with God, get me out of here and I’ll start over, no more hunting, no more of this, I promise, I promise. Half an hour later I’m still praying, last chance, half dead in the clearing of golden tussock in a creek bed, middle of nowhere. Then as suddenly as a light turned on something incredible happens - I know where I am. I’m being shown how to get back to the camp, I recognise this place, I know exactly what to do to make it out of here. I can make it.

“He who chooses the Supreme has already been chosen by the Supreme. God has chosen each of us before we even dreamt of accepting Him. But now that we are consciously aware of His acceptance, we need not stumble, we need not walk, we need not march; we can run fast, faster and fastest, because our awareness itself is God’s infinite Grace.”

Sitting in the yellow tussock, worn down to nothing, I stare out at an exquisitely beautiful world as though for the first time, a child’s awe, eyes streaming with tears. Stretching out in a cocoon of huge gratitude on the earth, all of myself merged into the mountains, trees, water, no ‘I’ left. A cloudburst of heart tears, a full hour unmoving.

“When we aspire with our heart’s tears, we see that God is coming down to us from Above. The heart is crying and yearning like a mounting flame burning upward. This flame of the heart wants to go beyond the mind, so it is always rising. And God is constantly descending with His Grace, like a river flowing downward. Ours is the flame that always burns upward; God’s Grace like a stream, is coming down from the Source. When aspiration and Grace meet together, we come to experience the divine fulfilment of union with God.”

“Jeez,” says Ken, “you look like hell! What happened?” A wild and desperate epiphany of tears, torment, grace, gratitude, elation. My whole life changed in three days. The plane labours up through skeins of wispy cloud then clear sky, the strip soon a tiny brown scar in the endless folds of earth, big distances stretching out of the cockpit window. From up here it all seemed simple enough, the jumbled hills untouched by the harsh geometry of manscapes, headwaters of wide rivers starting out in lonely shingled valleys, the flanking upthrusts of mountains like wrinkled calico, their scree slides tumbling down through dark forests as though gouged by a monstrous claw, topography laid out in an ancient asymmetry of order; and my own life clear and simple too, stepping back in altitude and distance to see the sense of it, its purpose unveiled by a near-death to this bright clarity. A feeling of the almost perfect inevitability of everything, all creation flowing towards some final and grand and peaceful fulfilment. Looking down at the snow-capped ranges, my harsh but grace-filled school room, feeling the diminution of self imposed by landscape, ridgelines stepping back into bluescapes of beyond, saying goodbye because I won't be back, at least not as this person who came here two weeks before. Remembering the moment when I stumbled out into that forest clearing and some veil parted, seeing everything as though for the first time, everything unfiltered by mind and custom—a grace-filled benediction—being shown something far beyond anything ever imagined. “Brace!” says Ken and we tense up against back rest and fuselage, no seat-belts in this old bird, banging down carelessly on the runway at Taupo. Stepping out onto the tarmac into the sweet cold air, hoisting up my pack and walking away, feeling a lovely freedom.

“God’s love gives us first a free access to His inner Existence, then a most complete intimacy or oneness with His inner Will and finally, ecstasy or delight, which is the universal and transcendental Reality which God Himself is.”

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

The Funniest Book Ever Written

by Noivedya JudderyWhat is the funniest book ever written? Humour is a personal thing, so I can only provide a personal answer. What book has made me laugh me laugh the most?

A pity that’s the question, because that means I can’t provide some kind of highbrow answer from the annals of classic literature. The works of Juvenal and Chaucer, the comedies of Shakespeare, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels... I’m familiar with them all, to a varying extent. They are all apparently hilarious. Unfortunately, I’ve rarely laughed at them. They lose something in translation. It is not merely the language, which has of course changed considerably. It’s true that “the past is another country” – and in these cases, a very distant country. You can learn the language, study the customs, even model a village (Disneyland-style) to resemble these countries – but there’s not a single airline that will take you there. If anyone today claims that they find Jonathan Swift much more side-splittingly funny than, say, Dave Barry, chances are that they are merely showing off.

For those who have not read Gulliver’s Travels, the title character doesn’t merely visit Lilliput (the land of small people, as seen in numerous children’s cartoons), but several other lands, where the people are equally unusual (in different ways). It was written in 1726, not as a children’s book, but as a satirical novel. Though much of the satire is still potent, it is based on the mores and government of eighteenth-century European society. Today’s people are similar in many ways, but society has changed just enough for Swift to lose his power. Like the political humour in a 30-year-old episode of Saturday Night Live, it doesn’t make so much sense if you weren’t there at the time.

Shakespeare presents its own problems to me. Twelfth Night, for example, is full of clever gags and witty one-liners, which I realised from reading the footnotes of a paperback edition I once bought. Of course, once a joke has been explained and analysed, you might “get it”, but it loses all appeal.

So for me (or anyone else), the funniest book is one in which the jokes make immediate sense, the laughter is spontaneous, and the voice is recognisable. With that in mind, I have to say that the funniest book ever written is Doctor Who: The Completely Useless Encyclopaedia (Virgin, 1996), by Chris Howarth and Steve Lyons – perhaps the only book I’ve read where the expression “laugh a minute” would come regularly. That’s just my opinion, of course.

Sadly, most of my friends could not share in the joy. This book was a snide glimpse into the world of Doctor Who fans. That was usually my favourite television show as a kid, and I was well acquainted with the organised fan community. When I bought this book, I was laughing at a world I know. (Howarth and Lyons later wrote a similar book attacking Star Trek in a similarly affectionate fashion. I found this one funny, as I’m familiar with Star Trek and I’ve known a lot of Star Trek fans, but not nearly as funny as their previous Doctor Who volume.) It’s a bit like sharing a joke among friends about people you know. However much she is making you laugh, you probably don’t say to your sharp-witted friend, “Say, you should be writing humour for a living!”

Away from the devoted but rather limited audience of the very talented Howarth and Lyons, the books that make me laugh the most have mostly been written in my lifetime, geared to (and satirising) the societies I know. Ben Elton’s Stark (and indeed, any of Elton’s earlier novels), any “Discworld” novel by Terry Pratchett (they all blur into one very long, very funny fantasy tome), Santo Cilauro, Tom Gleisner and Rob Sitch’s Lonely Planet parody Molvania, Douglas Adams’ Life, the Universe and Everything… You would be unlikely to find those on any literary scholar’s list of the greatest works ever written, or even the greatest works of humour. (Where’s James Thurber on that list?) Yet for this reviewer (and scores of other people, I might point out), they worked perfectly.

Fortunately, some humour has survived the test of time – for decades, if not yet centuries. If asked to name my favourite book, and keen to name a “classic” to prove my literary smarts, I would name Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. A brilliant anti-war satire (for those two or three people who didn’t already know), it has some moments that seriously had me in the classic situation of laughing uncontrollably in public. (I don’t know if I was in a train, but people noticed, with smirks of delight rather than frowns of concern. Perhaps, when they saw what I was reading, they just thought “Oh, fair enough…”)

But then, Catch-22 is equally memorable for its dark moments, in which the only laughter would be nervous (or pretentious). So if asked to recommend a humorous, pre-Gen-X book to a friend, I would suggest Jereme K Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog) .

This was written in 1889, so Jerome was a contemporary of Mark Twain and Oscar Wilde. While I enjoy the works (and of course, the pithy one-liners) of those two gentlemen, I believe that Three Men in a Boat has dated even better. Like Twain and Wilde at their best, Jerome focused on the whimsical nature of humanity rather than on politics and current events. This book tells of a boating holiday down the Thames with two friends, in which… nothing much happens. No matter, as Jerome must have been a fine raconteur. He continually digresses to other anecdotes about everything from cheese to opera singers, before pulling himself back to the story at hand, such as it is. If this has lost anything with time, it must have been a dangerously funny book when it was first published.

I know little about Jerome. He wrote other books (including a wonderfully-titled collection of essays, Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow), which I have somehow never sought to read. He claimed that the stories he so colourfully collected in Three Men in a Boat were completely true, but I’m not totally convinced. Whatever the case, to put the matter to rest, I feel confident in saying that he wrote the Funniest Book Ever Written (that wasn’t related to Doctor Who). Once again, that is only my not-so-humble opinion.

Noivedya Juddery Canberra, Australia

The Divine Hero by Sri Chinmoy

by Sharani RobinsSri Chinmoy’s book on spirituality, The Divine Hero, boldly encourages us to embrace the challenge of living as a hero – to bravely embark on a spiritual journey and discover that “we came from the Blissful. To the Blissful we shall return with the spontaneous joy of life.” The Blissful to which he refers is the spark of God deep inside waiting to be revealed and manifested.

Each one of us has a special role to play in God’s “divine game” but rarely do we achieve it. What keeps us from knowing and expressing these profound truths? Sri Chinmoy states it is because “in each human being there is a constant battle going on between the divine and the undivine.”

This book provides a detailed exploration of this interplay of light and darkness within ourselves and in the world around us. A definitive guide to both the barriers and helpers which “transform our suffering into joy and our darkness into light,” an entire chapter is devoted to each tool that helps us win in the battlefield of life. These helpers are simplicity, sincerity, purity, aspiration, dedication and surrender. Likewise, he sheds light on the qualities which create serious obstacles in our journey towards self-conquest: insecurity, fear, doubt, lethargy and self-indulgence.

As we read about these issues all too recognizable in the frustration they cause in our lives, Sri Chinmoy patiently and convincingly insists that if we can discover and manifest our unique divine mission on earth, satisfaction is bound to dawn in our life.

He encourages us in our mighty conquest by assuring us that “the path of world-acceptance is undoubtedly the path of heroes. We have to fight against doubt, worry, fear, obstruction, limitation, imperfection, bondage and death. But if we really love God, then nothing is difficult. Everything becomes very secure and safe. This is the easiest and most fulfilling path for the sincere, for the totally dedicated, for the brave souls who are ready to walk, march, run and fly along the path of Eternity.”

The style of Sri Chinmoy’s writing encourages confidence as well. While the book offers an in-depth treatment of lofty and profound spiritual concepts, it is rooted in understandable language and includes instructional stories, poems and aphorisms. All in all, The Divine Hero is a potent tool that inspires bravery at the same time that it demystifies life’s thorniest difficulties. Once read, you will be inspired to dive deeper in your own hero journey.

Sharani Robins Rhode Island, USA

The Winter Of Our Discontent by John Steinbeck

by Alf ZolloSteinbeck: a mighty icon of American literature with a prolific output. A close observation of this life lived in words allows us to trace the personal evolution of the author. His best-known works are The Grapes Of Wrath and Of Mice and Men. The Grapes of Wrath is a testament to unyielding sorrow and Of Mice and Men deals convincingly with hope and disillusionment. The Winter of Our Discontent arrives to herald the triumph of hope. We can discover in it the song of the heart’s victory.

It is the story of a man living in a small town in New England. His name is Ethan Hawley. A man without a lot of ambition, he lives a simple existence but feels burdened by the many obligations imposed upon him by his family, friends and community. The seeds of self-betrayal are sown when he asks himself, “Suppose for a limited time I abolished all the rules, not just some of them. Once the objective was reached, could they not all be reassumed?”

His choice is to discard the voice of conscience in the pursuit of power. Once he betrays his own ideals he finds himself betraying his best friend, his wife and his boss. All of these events serve as a mirror to the social change occurring in America. Steinbeck uses Hawley’s experiences to critique the preoccupation of contemporary western societies with money and power. This aspect of the book is illustrated by his own son’s involvement in a competition and the outcome.

Ethan is a man who takes refuge in his own inner life. His being is populated with characters from his past that he calls upon for advice. There is a Great Aunt and the Old Captain who represent aspects of his own experience and wisdom. He defers to them in times of need, conversing with them in the moments before sleep when the boundaries of other worlds become elastic to consciousness. These intriguing passages show the fertile power of imagination and its sustaining quality in human life.

Within the book, there are contradictory representations of women. On the one hand is Ethan’s nurturing, patient, sweet wife, whom he adores but is unable to fathom. She represents Mother Nature, with all its vast reserves of patience and tolerance. At the opposite extreme is the calculating Margie, who seeks only to exploit others in all her relations. Between these two representations is Ethan’s own daughter, yet to blossom into womanhood. She serves as the catalyst to save him when he finds himself devastated by his actions and incapable of living in his world.

We are with Ethan when he realises that the hopes and dreams at the core of each heart is what ties human beings together — despite the apparent loneliness of life. The vicissitudes of existence are wont to obscure them but briefly. At the end of the book, we climb out of the “mind-prison” with Ethan and know that the strength exists within us to continue our journey despite the past. This is our destiny.

Steinbeck was deservedly garlanded with the Nobel Prize for Literature the year after The Winter of Our Discontent was published. Even the casual reader will find much in it to appeal - Steinbeck has a wonderful ability to reveal the layers of humanity we all possess. I hope you enjoy this book.

Alf Zollo Canberra, Australia

The Tale Of Genji: The World's First Novel

by John-Paul GillespieWritten by the Japanese noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu in the early eleventh century, The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature concerning the son of a Japanese emperor, his romantic life and the customs of aristocratic society at the time. Called alternatively the world's first novel, the first modern novel or the first novel to be considered a classic; precisely which is a matter of debate by those who make a living debating such things. Nobel Prize winning novelist Yasunari Kawabata named The Tale of Genji "the highest pinnacle of Japanese literature. Even down to our day there has not been a piece of fiction to compare with it."

The Tale of Genji was written for Japanese women of the yokibito, or aristocracy, and possesses many of the elements found in novels today: a central character, major and minor characters, well-developed characterisation, psychological insight, complexity, sequential events taking place upon a timeline based upon the central character's lifetime. Rather than using a plot, events just happen and characters evolve simply by growing older, much as in real life. The internal consistency of Genji is a notable feature, and evidence of Murasaki's skill; all characters age in relation to each other, and relationships between them remain consistent throughout chapters.

Unusually, none of the characters are referred by name in the novel, a complicating factor for modern readers and translators alike; they are referred to instead by their function, role, honorific or relation to other characters; for example 'Minister of the Right,' 'His Excellency' or 'Heir Apparent.' Lack of names was a feature of Heian era court protocol, which decreed their use in a public forum as unacceptably familiar.

There is debate over how much of the Genji was actually written by Murasaki Shikibu herself, with some of the novel's later chapters containing discrepancies in style and rare continuity errors, with scholars suggesting that Shikbu's daughter Daini no Sanmi may have completed the novel. A further complication is the fact that the tale ends abruptly, in mid-sentence, probably not as intended by the author herself.

Written to entertain women of the aristocracy in eleventh century Japan, the novel employs Heian period court Japanese: highly inflected language with extremely complex grammar. Poetry is often used in conversation, as was the custom in court life, with classic poems modified or rephrased according to the situation at hand. Of the classic Japanese tanka form, the poems would have been well known to the intended audience, and are often left unfinished as if thoughts unsaid, the reader expected to complete a word or sentence— a complicating factor for a modern readership unversed in Heian era poetry.

Intended for a female audience and by a female author, the novel was written entirely in Hiragana script, so-called a "women's hand" at the time. All official documents, essays and works of history were written in Chinese characters and only by men, producing the paradoxical situation where men wrote mostly in bad Chinese while their spouses produced excellent works in native Japanese. Women's prose and poetry from this period, of which The Tale of Genji is pre-eminent in same manner as Shakespeare in English, form the basis of what in time became a truly national literature, as poets switched from Chinese to the new Japanese scripts for their elegant simplicity and flexibility.

John-Paul Gillespie Auckland, New Zealand

The Year of the Horse by Sam Mahon

by Barney McBrydeEvery weekday morning in 1984 I rose and drowsily guzzled down my lumpy porridge before pedalling off across the dark and sleepy city to Canterbury University. I could do the whole distance with my arms folded if I put my mind to it. Once there, I laboured to the very top of the James Height Library Tower, to the rarefied realms of the Classics Department, where, in a little room at the end of a corridor, a small group of students gathered around she who was called ‘Kate’ by the fearsome Professor Lee, but who we deferentially addressed as ‘Dr Adshead’. She sat there each morning in her neat hounds-tooth suit and taught us ancient Greek.

Ah! To read Plato and Sophocles in their original tongue; to leaf through the New Testament and read the words of Christ in the language they were written in!

It is interesting to note that one of the reasons that the upper, educated classes of ancient Roman society did not noticeably adopt the new religion of Christianity was that they found its scriptures to be offensively badly written. To ears attuned to the high rhetoric of Cicero, the poetic flights of Virgil, the ancient exactitudes of the Greek philosophers; the mundane and pedestrian narrative of events in distant Palestine held little appeal. The jottings of provincial tax collectors and fishermen did not appeal to the literati of the glittering capital of the world. Today people expound upon the glorious literary heights of these same scriptures. How our standards have fallen since the days of Cicero and Pliny! But we live now in the post-literary age. The twenty-first century wants a picture to look at not a text to read. On the BBC the experts discuss the ‘YouTube generation’ wherein a thousand words in not even an option.

I was recently in a bookshop and my eye chanced upon a startling volume – ‘The Manga Bible’; the attenuated Japanese figures of Christ and His disciples ‘biff’-ing and ‘pow’-ing across the pages. There it was: Cicero’s worst nightmare – an age in which the words that he and his ilk had found so wanting were considered just too high flown and demanding that they needs must be whittled down to a few pictures with speech bubbles. I picked it up and leafed through it. “Coooool. Colon, close brackets,” I thought, in my best post-literary fashion.

If nobody reads a book with words in, what then is the point of a book review? A book review, surely, is merely a formalisation of that most natural responses to reading a good book: telling your friends about it and encouraging them to read it, that they may share the experience which you have had with the book. If nobody reads, we could spare ourselves the trouble of producing a book review.

But wait! There remains one place on earth wherein the book still reigns, where literature is treasured and valued. There is a place where the citizens buy and read more books than in any other place on the globe. Where is that place? Surely some cultured nation steeped in the ancient traditions of literature. In the shadow of the Acropolis? On the banks of Shakespeare’s Avon? In Dostoevsky’s Russia? The cafes of Paris where the greats of French literature once gathered? No. The nation where the book is read most is . . . the land of rugby and beer, the pioneering land of the rugged laconic outdoors man, the land of the hardy sportsman and the gimlet-eyed mountaineer, the land where sheep outnumber humans by 20 to 1 – New Zealand.

This being the case, if we are to review a book – best that we consider a book by a New Zealander.

If you fly into Dunedin – the small city which is the centre of the southern half of New Zealand’s South Island; the city called ‘the Edinburgh of the South’ for its origins in Scottish settlement, not to mention its bleak weather and dour inhabitants – you exit the airport terminal building and cannot help but notice to one’s left a life-size bronze statue of a man on a horse. In another country an equestrian statue would be of some pompous national hero or military figure from the past, noted for his skill in butchering the enemies of his homeland. Here it is of a rough shepherd mounted on a rather tubby old work horse. The statue has been there for some years now. There are those who have never liked it much, but since we aim here at a book review and not art criticism let us pass by without expressing any judgement. The work was sculpted by a noted New Zealand sculptor: Sam Mahon. ‘Noted sculptor’, but one might add ‘noted author’. Sam Mahon’s first book was called The Year of the Horse and is an account of the year in which he was commissioned to produce the horse, constructed it, cast it and installed it. So far so dull, but Mahon is an artist of words as much as of clay and metal. His account is more like a poem than dull prose. The life of art, the life of rural New Zealand, the ethos that New Zealanders admire and excel at of mucking in and getting things done with a welding torch and a piece of number eight fencing wire – it all sings from the pages, as does his love of the river; the mountains; the sky; the hard, tough grind of making art.

I have long maintained that the greatest sentence ever written was Tolstoy’s describing the death of Anna Karenina. There is a sentence in The Year of the Horse that, for me, challenges the primacy of that sentence. You will have to read the book yourself. I recommend it. And what is the alternative – the Manga Bible?

Barney McBryde Auckland, New Zealand

An Extraordinary Egg by Leo Lionni

by Mahiruha KleinOne of the most interesting courses I took in college was devoted to children’s literature. It was so interesting because it was totally different from my expectations. I thought books for children should be light, fun and easy to read.

The professor, an amazing scholar and thinker, explained to us that really great literature for children is exactly that- real literature. People who write good books for children seek first and foremost to write; and they write out of a love of language or a need to communicate their ideas. Their books are works of art.

Bad children’s literature, on the other hand, is clumsy, cutesy, redundant and intellectually offensive to children and adults alike. I can reel off a list of books and movies for kids which fit these adjectives to a tee!

Of all the writers we studied, I came away most impressed by two: Maurice Sendak and Leo Lionni.

Maurice Sendak wrote the wonderful Where the Wild Things Are as well as the incomparably great works We Are All In the Dumps with Jack and Guy and In the Night Kitchen.

I once saw a print of one of Sendak’s sketchbooks. It was filled with scribbles, miniature cartoons and interesting urban landscapes. Under each drawing or image, he wrote what piece of classical music he had been listening to while he worked. I was not surprised by this. His work is musical, fantastical and yet always convincing- heartfelt even in its most outlandish flights of fancy.

I went to the Queens Central Library the other day and picked up An Extraordinary Egg by Leo Lionni. It is a story about three frogs, Marilyn, August and Jessica. Marilyn, the oldest, “knows everything about everything”. August keeps silent in the story, he is just an observer. Jessica, the youngest frog, is an explorer, a restless wanderer. One day she finds what she thinks is a pebble, unusually white and smooth.

When Jessica eagerly rolls the pebble back to where the three frogs live, her sister Marilyn informs her self-righteously that she hasn’t brought back a pebble, but a chicken egg. The egg hatches, and sure enough what emerges from it is an alligator. None of the frogs have ever seen an alligator themselves, so when the baby ‘gator emerges, Marilyn can crow triumphantly “I was right! It is a chicken!”

Jessica and the baby “chicken” become fast friends. The “chicken” can swim surprisingly well and even saves Jessica’s life one day when she waded into too-deep water.

Jessica and her little faux-chicken friend have lots of good times together until one day a little multi-colored bird spots them and lands right beside them. It tells them that Little Chicken-Not’s (my phrasing!) mother has been looking desperately all over for her. The bird guides the two friends to where her mother, a giant alligator, is taking a siesta. Upon sensing their presence, she “slowly opened one eye, smiled an enormous smile, and, in a voice as gentle as the whispering grass said, ‘Come here my sweet little alligator.’”

Jessica tells her buddy that it’s time for her to go, but asks her to come visit her and the other frogs soon, and to bring her mother with her. When she returns home, she tells her friends that the “chicken’s” mother referred to her daughter as a “sweet little alligator.” The story ends with the three frogs doubled over with laughter, as her mother can’t tell that her own offspring is really a chicken, albeit a green chicken with scales, a long tail and razor sharp teeth.

Like almost all of Lionni’s stories, this book encourages the reader (not necessarily only the child reader) to examine and to question authority. I mean, Marilyn thinks she “knows everything about everything” but she’s actually just ignorant and decisive- a good recipe for disaster!

There’s something mysterious and elegiac about Lionni’s use of color which reminds me of Gaugin. I especially like the way he shows the impact of light by lightening or deepening colors- especially greens- from frame to frame.

He also uses color to imply emotion. When Jessica first rolls the “pebble” up the little mound where the frogs live, the cluster of flowers on the top of the mound are rendered in deep but brilliant crimson, with a rich blue light between the stems to bring out the effect of the red. On the next frame, the reddish color is airier and more subdued, and there is no more blue color between the stems; the frogs have recovered somewhat from the surprise that this newly discovered egg has brought them.

I really admire and enjoy the stillness and dignity of Lionni’s writing. Towards the beginning of the book we have this beautiful passage: “One day, in a mound of stones, she found one that stood out from all the others. It was perfect, white like the snow and round like the full moon on a midsummer night.”

I like Lionni’s use of symbolism and imagery. When Jessica and her friend encounter the mother alligator, we see the same red tulip-like flowers again- perhaps indicating the degree of their surprise or alarm. The title An Extraordinary Egg is intriguing because of the connotation of eggs, and what comes from them- in this case, chickens. Eggs can be symbolically associated with many things, including life, dreams and mystery. Chickens are associated with sacrifice. It’s interesting how Marilyn, the know-it-all, puts all of the frogs in mortal danger by being so sure of the alligator’s identity. I mean, the story ends with Jessica and her friends laughing about how the mother alligator could be so stupid in miscalling her child “alligator”; but the joke is emphatically on them!

Sendak and Lionni are two great writers whose books surprise and enlighten children and adults alike with their depth and vision. I’ve certainly grown as a human being by reading and enjoying their work.

Mahiruha Klein Philadelphia, USA

Our members

Stories

First-hand experiences of meditation and spirituality.

Sri Chinmoy's biography, written by one of the most famous Bengali authors

Mahatapa Palit New York, United States

If a little meditation can give you this kind of experience...

Pragya Gerig Nuremberg, Germany

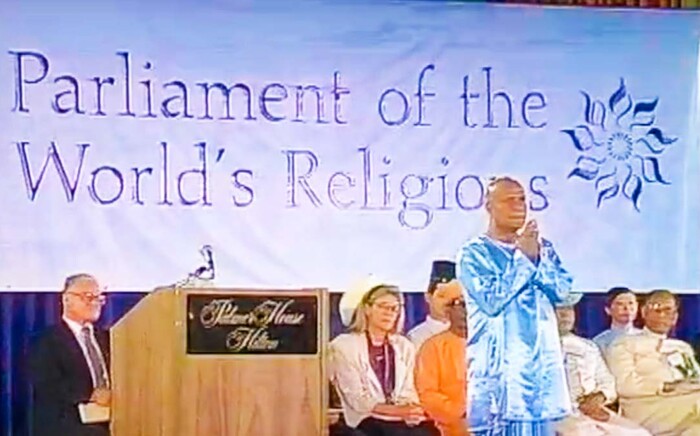

Sri Chinmoy's opening meditation at the Parliament of World Religions

Pradhan Balter Chicago, United States

The Swimming Relay

Toshala Elliott Auckland, New Zealand

Having a Spiritual Teacher

Preetidutta Thorpe Auckland, New Zealand

A 40-Year Blessing

Sarama Minoli New York, United States

The Impact of a Yogi on My Life

Agni Casanova San Juan, Puerto Rico

I was what you call a classic unconscious seeker

Rupantar LaRusso New York, United States

A vision at 3 a.m in the morning

Abarita Dänzer Zürich, Switzerland

Breaking the world record for the longest game of hopscotch

Pipasa Glass & Jamini Young Seattle, United States

Your life's responsibilities compel you to develop inner strength

Pradhan Balter Chicago, United States

The day when everything began

Bhagavantee Paul Salzburg, Austria

So much longing, for something

Pushpa rani Piner Ottawa, CanadaSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

My first impressions of Sri Chinmoy's philosophy

Lunthita Duthely Hialeah, United States

When I met Sri Chinmoy for the first time

Baridhi Yonchev Sofia, Bulgaria

My daily spiritual practises

Muslim Badami Auckland, New Zealand

How Sri Chinmoy appreciated enthusiasm

Prachar Stegemann Canberra, Australia

What drew me to Sri Chinmoy's path

Nikolaus Drekonja San Diego, United States

A feeling that something more exists

Florbela Caniceiro Coimbra, Portugal

How meditation helped me swim the English Channel

Abhejali Bernardova Zlín, Czech Republic

Except where explicitly stated otherwise, the contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. read more »

SriChinmoyCentre.org is a Vasudeva Server project.