Inspiration Letters 26

Running is sometimes really difficult for me. I get shin splints very easily, and often my knees ache. But, nothing gives me the kind of exhilaration, the sense of limitless freedom, that running does. I think Sri Chinmoy said somewhere that, when we run, each breath we take is connected with a kind of higher reality. He said that running connects our breath with a higher, spiritual breath, and that divine breath is like a blessing for our entire physical body. (You can find his discussion of this phenomenon here).

When I turned thirty, I got up early in the morning and did hill work on the big steep hill on 150th street between Hillside Avenue and the Grand Central Parkway. Trust me, it is an unbelievably steep and difficult hill! As I was running up and down the hill, I saw a frail old man, very nicely dressed, walking up the hill. He was a little bent over, almost crooked, and was obviously moving with difficulty. The fourth or fifth time I passed him, he waved and smiled at me and told me to keep it up. I noticed he had an accent and I asked him where he was from. He explained to me that he was from Haiti and that he had recently turned ninety. I was so moved that both of us had birthdays on practically the same day and we were both challenging ourselves on the same cruel hill. The man was fluent in Spanish, so we were able to have a nice conversation.

These days I don’t run much. I do more work with weights and I also swim a little. Maybe I should put together a modest running schedule and see how faithfully I am able to stick to it. I miss the long hours I used to spend running along Union Turnpike and in Alley Pond Park.

I am not fast and have never been a fast runner. But, I still get lost in my own slow rhythm, and it’s easy for me to forget my problems under the sky, and in a big wooded park. I have so much clutter in my room and in my life! When I run, I feel totally free. Running keeps me simple.

Simplicity is something I have lost sight of recently. I mean, I was going through some boxes in my closet and I found some of my old notebooks, journals. I opened one of my old diaries, and found I had filled page after page with Guru’s aphorisms- inspiring poems from his “Christmas Trip” pilgrimages to various parts of the world. One poem I had copied out was:

Life is short.

Hope is long.

Promise is vast.

Promise-fulfillment is perfect perfection.—Sri Chinmoy, My Christmas-New Year-Vacation Aspiration-Prayers

Maybe I should go back to copying out Guru’s short inspiring aphorisms!

I like how this poem contrasts the brevity of life with the length of hope and the vastness of promise.

Sometimes the spiritual life can seem repetitive. I know of Zen Buddhist monks who tend the same little garden every day for hours and hours to remind themselves that even the tiniest tasks deserve to be done with respect and devoted attention. Like that, I find that my spiritual life is composed of hundreds of little tasks. These include daily prayers and affirmations, keeping my room clean and organized (that’s an uphill battle to make the hill on 150th street look like a piece of cake!), doing spiritual reading, keeping a meditative journal (Inspiration-Letters has definitely helped me a lot with this) and exercising. Sometimes I make a checklist, and when I do everything on the list, I go out to the local ice cream shop and order a large bowl of frozen custard. As for the last item on the list, exercise, I often turn to Sri Chinmoy’s poems for the final burst of inspiration I need.

One old poem I like a lot is this one:

In Supreme Gratitude

Lord,

I wish to shine

In supreme gratitude;

Therefore

I am awake,

I am walking,

I am running,

Toward the golden Destination-dance.—Sri Chinmoy, excerpt of poem 392 from Transcendence-Perfection

I like how, on Sri Chinmoy’s path, poetry, exercise, meditation and service to the world all go together. His is one of the rare integrated paths of yoga that is all-welcoming, all-affirming. In the poem I just quoted above, I like how the destination itself is a dance; it is not static. We wake up, walk, and run so that we can finally join in that mysterious dance that is the very cosmic rhythm of the universe. Save me a lawn chair for the next marathon. I might not run, but I will definitely cheer.

Welcome to the Running Issue, dear friends!

Mahiruha

View: Inspiration Letters as PDF

A Runner’s Diary

Ah this cold winter. Peering outside into a dreary grey dawn, at sagging clouds and wet glistening roads and footpaths with their banks of sodden leaves; and to the east the apricot blush of sky above the harbor, its serpent tides tugging at the roots, the kelp beds. Warm bed calling me back. Force yourself out the door. Coddled head to toe out I go. On Graton Bridge, a group of overweight women thunder past me as though I’m standing still — bare arms, bare legs, tough girls unperturbed by winter. These plumes of misty breath, breath of my life, marrying me with the sky. James K. Baxter, that immensely great poet, brooding and drunken lived here, saw this tide of people scurrying to work each dawn as I do. And there, a poem of his still up on a café wall:

Alone we are born

And die alone;

Yet see the red-gold cirrus

Over snow-mountain shine.Upon the upland road

Ride easy, stranger:

Surrender to the sky

Your heart of anger.

The dark sky droops like a soggy canopy, each step is a triumph of will — if I can reach Remuera Village without stopping I’ll be satisfied. Under my breath singing my today’s favorite song — ma eseche, ma eseche, ‘Mother you have come….’, my invocatory mantra. I like the aloneness of running, its simplicity, splashing across the waterlogged parklands in my muddy shoes, chilled feet leaving my signature tracks in the muddy grass like the spoor of a night animal, talking my foolishness to God. Ma eseche…yes you have come, we are cradled by God.

Tuesday

At my morning shrine Guru’s words spiral off the page of a book…. “Spirit is creative, conscious existence. What is matter? It is anything but lifeless, mechanical substance. Matter is vibrant energy which deliberately hides within itself life and consciousness.” (Sri Chinmoy, Yoga And The Spiritual Life. The Journey of India's Soul)

It is remarkable that spiritual masters — and here, Guru himself — ‘see’ into the fundamental nature of reality and the discoveries of quantum physics, that ‘vibrant energy’ and consciousness are the ground of all being and the very matrix of the universe. Everything material emerges from the infinite unmanifest, the sub-strata of potentiality, and consciousness itself manifests the worlds of our external and internal experiences. These insights imply a mind-created, dreaming universe and were self-evident even to the sages and yogis of past millennia.

Guru often spoke as well of the cosmic energy pervading everything, its accessibility to the receptive athlete, and that if there is a tug-of-war between strength and power, power will always win, ‘for the source of power is infinitely greater than the physical strength that any human being can have.’ Reading of these revelations, remembering them while running today, I was wondering how to take the quantum leap, how to run a sub 3:30 marathon in August, fill my being with the vibrant energy of the cosmos. Is it too late to reactivate this superannuated body and race away to a stunning age category victory? If I dream this, then perhaps, perhaps….

Wednesday

Kanala is here from Austria, a whirlwind sprint around the country, four centres and cities, five sitar concerts in a clutch of days. We take him out to Auckland’s west coast forests in the early hours for an amble in the 60 miles of plantations. This sweet clean air, the sea sighing all around us in the sound chambers of forest, the unburdening calm of a high sky and these undefiled hours. The lovely freedom of wanting nothing else. Wet spear grass, the dusty pollen of the yellow flowering ragwort, ocean combers breaking, echoing up in the tall canopies of pines, sometimes a silent urgent hand pointing up ahead — there! — the flick-flicker of a white rump darting away silent through the trees, a hind and fawn. I am thinking of the shape of my life, of things sensed in the seas proximity, the unbreakable perimeters of my nature, a sense of despondency that I have not ventured more. The trail recedes away but will not take me any closer to an understanding of these things.

Thursday

Consider this evening’s gifts, the fading light above the rim of earth and the streets filling with my human family, seen but never to be known, though I would like to single out a stranger or two, saying “can we talk for a while?” Stare out the window, complain of the weather, of the wind bludgeoning the manicured pampered trees along Karangahape Road.

In his book The Outer Running And The Inner Running Guru writes: “Unless you touch something every day, it does not shine. Often I have told people to touch the furniture in their homes every day. As soon as you touch something it gets new life. If you are aware of something, immediately it shines and gets a new luminosity. If you have good health, if you touch your health every day, it gets new life.”

So I go out, Thursday’s trot around a block or two, my feet pattering and rhythmic on the sidewalks, seeing all the familiar desperate things, eateries steaming up, the pubs with their lonely cargo and I remember Roethke’s poem, his line ‘agony of crucifixion on barstools’. Yes it does seem like that. Three miles then home.

Friday

I like to run early when the dawn comes, the slow gray light flushing up into the black canopy, a city slumbering and quiet. This is the hour of the songsters, the thrushes and blackbirds — and sparrows have the streets, squabble over scraps. In the human world only a few homeless ones are about, stirring in their damp blankets and newspapers. Hunched on a park bench, sometimes they curse me — I am too privileged, too remote to be accepted.

I don’t need an alarm to awaken — one of our disciples, unfailingly on time, visits the centre early and I hear the little sounds of movement, the subtle shift of energy in the darkness. The building squeaks and creaks, awakens like a sentient being.

She comes to the Centre every morning around 3:30 am, the holy hour, for her early three hours of meditation. She is quiet as a falling feather but the old wooden floorboards and creaking joists betray her, shift and sigh as she passes my room. In her hour long walking meditations, her slow circling shuffle around the great room, she claps her hands together just once when thoughts come, a novel rebuke to her mind. Lately she has found a tiny brass bell shaped like the corolla of a golden flower, and rings it to alert herself when her mind trails sleepily away. I hear it from far away, ting-a-ling-ling, ting-a-ling-a-ling. I like lying awake in the early morning’s silence, feeling the sincerity and the quest for God impressed in to the darkness, and from time to time the tinkling of the penitential bell like a call to remembrance and prayer.

I remember in the 80’s there was a TV series, all about the Shaolin monks, called Kung Fu. The enlightened master tested his disciples’ progress by having them walk across a rolled out length of rice paper — when enlightened, supposedly their footfalls would leave no trace. Our walking is a register of our consciousness: some have little awareness and walk into the meditation room like elephants, ponderous, the whole room trembling. But at night she walks past my door like a wraith, silent as a shadow, leaving little imprint on the rice paper. Only far away in the other room I hear her thoughts, the clap of hands or lately the muted ting-a-ling rebuke of the tiny brass bell.

Saturday

We held a public race today in the drizzle — 150 people come. After prize-giving they dawdle and talk, eat porridge under the tent, enjoy the camaraderie that running elicits. You can talk to any stranger — ‘how was your time today?’ The winners so uplifting to watch, shining with rain as they pass, the girl glissade-smooth, almost floating, the boy all muscular concentrated power. Effort and transcendence have made them happy, they smile, their hearts shine. Guru likens running to a family picnic — body, vital, mind, heart, soul all fed and satisfied — and to the perennial journey, the ultra-marathon back to God. I am the marathon Guru, he said. We gather to watch the children’s 1.5 km event, the way they flew down the hill at top speed, all enthusiasm and unrestrained joy, a sprint, the gauntlet of parents and adults all huge smiles.

Last night in the Centre we were talking about the need to be a disciple at every moment, and that consciousness is our main manifestation — standing in the street, buying an apple, sitting on a bus, be a disciple. This week one of our girls, simply walking down a road, had been asked by a discerning stranger, ‘Are you with the Sri Chinmoy Centre?’ So today at the race we are all smiles, we are smiling at everyone and practicing our karma yoga.

Sunday

I have been good, run every day. In my morning book Guru asks me… “Why is it that in you the inner cry has increased, whereas others are still fast asleep? It is because God has inspired you. It is not that you just come out of your house and decide to run. No, something within you, an inner urge, inspires you to go out and run. And who has given you that inner urge if not our Beloved Supreme?” (ibid)

I profess to being truly grateful for the enduring gift of fitness and the grace of inspiration in my inconsequential life. Sinews, bones, muscles still work — I have been granted an extension. Although now in my sixties, some days I feel as though I’m twenty years old, I could run forever along the promenade above the Hauraki Gulf, lope out along the headland and watch the ocean-going yachts battering through the chop and big green swells of open seas, or head west with a knapsack and run the empty mountain roads that rollercoaster through forests of overarching ferns, tall kanuka, white blossoming clematis, the earth’s incense, breathing the pungent and fragrant spices of the soil.

My running reflects my nature a lot, I like the same circuits which I revisit, the streets and mountain trails, riversides and parklands, secure in these familiar places. My wider life is circumscribed like this, the perimeters quite narrow and defined, the repetition of days that welcome familiar things. There are the other circuits we travel as well, revisiting the great stations of human life — loneliness, anxiety, remorse, hope, desire and anger. We see them in each other, but do not talk of them, accepting the old covenant of silence.

Don’t we each have too in our lives a personal standard or feeling by which we measure our living and our satisfaction? Perhaps it is the standards and expectations of our souls. For me running is a barometer of all this, the litmus test of my risings or fallings…it keeps me at a certain level, ensures that I maintain this personal standard. In the complex landscape of a busy and multi-faceted life, running is a constant, like eating, sleeping, meditating, an essential ingredient underpinning the physical and spiritual, and without this the other things might weaken or falter.

Running too is a happiness of sorts, a celebration of life and that aspect of life which is movement and dynamism and will — and running confers life as well. Running is the battle against ignorance — it challenges the reluctant mind, the bed-loving body, the gravitational descent into age and infirmity and ordinariness — and masters them. Running, although in the physical, exercises the soul’s further-reaching will.

Guru reminds us: “If you want to run fast, faster, fastest, then you have to simplify your outer life, your life of confusion, your life of desire, your life of anxiety and worry. At the same time, you have to intensify your inner life, your life of aspiration, your life of dedication and illumination…. Your own higher self is the goal that your lower self has been searching for.” (ibid)

With practice, running can also be meditation. Some days when I’m failing miserably at my shrine, I head out for big open spaces, sing songs or chant or talk to God. And coming back over Grafton Bridge today I see one of Baxter’s poem, ‘To our Lady of Perpetual Help’, in that loyal café window — the last few lines tingle in my mind like this lovely sunrise:

…Mary, raise

Us who walk the burning slum of days

Not knowing left from right. I praise

Your bar room cross, your star of patience.

Running: Poetry In Motion

Running is a subject that many people these days are quite familiar with. Whether through their own direct experiences of running themselves or by their knowledge of running through the media coverage that is so prevalent these days with running events, I am sure most people have heard of words like ‘marathon’ or ‘relays’ or ‘ultramarathon’ or ‘sprints’.

Running is a subject that many people these days are quite familiar with. Whether through their own direct experiences of running themselves or by their knowledge of running through the media coverage that is so prevalent these days with running events, I am sure most people have heard of words like ‘marathon’ or ‘relays’ or ‘ultramarathon’ or ‘sprints’.

Through my own experiences of running and racing throughout the last four decades I have experienced a full spectrum of the emotions of personal triumphs and defeats as well as just the satisfaction of easy jogging just for the sake of fitness and relaxation.

For me and other friends who I know approach running as a spiritual discipline, running can be best described by songs and poetry, especially by our Spiritual Guide or Guru, Sri Chinmoy. This is one of my favorite poem/songs that offers a spiritual perspective on running.

Run and Become,

Become and run.

Run to succeed

In the outer world.

Become to proceed

In the inner world.—Sri Chinmoy, Run and Become

Running not only offers an opportunity for fitness and health, but also embodies the qualities of dynamism and strength which can be helpful in our day to day lives in this fast moving world. Yet another aspect of running which may be overlooked or misunderstood by many is the quality of rhythm and a sense of art or poetry embodied in the act of running.

There are many ways to try and describe this experience of the art of running just as there are many ways to run. In the following poem I will try to offer one aspect of running which is quite unique and perhaps misunderstood in the world of running and racing in general. It was inspired by running in the longest certified footrace in the world, the Self-Transcendence 3100 Mile Race, which has been held every summer since 1997 around a half-mile block in New York City.

Rather than try to describe or explain it any further, I will just offer the poem here with the sense of poetry as its theme. Since poetry can creatively express and embody the full range of emotions experienced in our unique human psyche, this race also involves the full spectrum of our human and spiritual emotions as we continually try to move towards a very lofty goal every day for almost two months. Therefore I named it, ‘Poetry in Motion’:

Poetry in Motion

A reality unique

As we circle the block

With no end in sight,

Seeing life unfold all around us

From sunrise to midnight.The energy intensifies

As the world slowly awakens,

Bursting with activity

For a time undetermined

As we continue our trek

Day after day,

Week after week,

With unrelenting determination and focus

Not meant for the meek.We strive for a goal indescribable

With our cries and our smiles,

Not defined by the limits

Of time nor the distance

Embodied by its name:

3100 Miles.Self-Transcendence

Is a more accurate description

Of this unfathomable experience

Of our progress towards a goal,

Where time is our friend

As long as we are in motion,

And where countless struggles

And boundless jubilation

Accompany us to the end.As we approach our final destination

Be it distance or time,

With indispensable help from our friends

We have successfully crossed

A formidable Ocean

Of patience and pain,

Sorrows and joys,

And in this unfolding process

With undaunted devotion,

We have become

Poetry in motion.

A Sweet Marathon Memory

When I was a relatively new student of Sri Chinmoy, it was customary for his students from all over the world to run the New York Marathon. Traditionally held on the first Sunday in November, all of us would wear the same Sri Chinmoy Marathon Team t-shirt as a kind of uniform for the team. The shirts would sport inspiring aphorisms by Sri Chinmoy particularly suited to encourage the reader who saw the shirt out on the course. Often times, bystanders along the route would call out “Go Sri!” when they saw us run by. The journey through all 5 boroughs offered a fascinating glimpse of the city with a sea of entrants crossing the Verrazano Bridge at the race’s start, children crying out for us to high five their outstretched hands and many bands rocking away with a beat to fill you with enthusiasm.

Each year that I entered the New York Marathon my love for New York City grew a little deeper. I completed about 17 miles the first time I ran in the New York Marathon with the Sri Chinmoy Marathon Team back in the mid-1980's. Since I had never done a marathon before and was not thoroughly trained for it, I felt content with that distance in my first ever attempt at running/walking 26.2 miles. However, the following year I was hoping and intending to actually finish.

Things seemed to be progressing well enough in that second marathon experience when I suddenly felt ill on the Pulaski Bridge that crosses from Brooklyn into Queens, located at the 13 mile mark. As I stood on the middle of the bridge, I knew I had absolutely no choice but to drop out because of the sudden dizziness and nauseousness waving over me. I recall that I was on the verge of fainting. I climbed onto one of the buses for people dropping out of the marathon and then took the subway back to the Jamaica Queens neighborhood where I was staying. I was pretty sad about completing even less than the previous year’s 17 miles. Once I got home, I soaked my sore muscles in the tub and tried to console myself by saying "well at least you did a half-marathon."

That night we had a meditation/ marathon celebration program after the race at a meeting hall called Progress Promise. People were announcing their times and telling race stories. At one point Sri Chinmoy asked who ran but did not complete the race. I was one of several hands that raised into the air from the audience and on my turn I announced that I had run 13 miles. He answered me with a kind and encouraging tone in his voice, "Oh, a half marathon!"

Needless to say, I was thrilled by his echo of my own consoling words to myself from earlier that day. I felt as if he had heard my thoughts that afternoon once I got home from the marathon and knew that I was discouraged by my marathon results compared to the previous year.

When I finally completed the New York Marathon for the first time ever the following year (by then my third try), I wept tears of joy after I crossed the finish line. I went on to take part in the New York Marathon a total of eight times, the last time being in November 2000. After that, our marathon team started a tradition of having a marathon in Rockland State Park every August rather than joining the New York Marathon.

I will never forget my New York Marathon experiences and to this day I especially treasure this early sweet memory when Sri Chinmoy uttered the simple words that I alone knew were rich with meaning — "Oh, a half marathon!"

Marathon Efforts

If pressed to name my favorite decade, ignoring the ones I actually lived through, I’d probably say the 1920s. That was a time when the coolest fads (not that “cool” was used in such a context back then) were the ones that pushed the limits of human endurance. Even the partying provided feats of derring-do. Flappers climbed the unfinished skyscraper buildings, which already towered over the cities, and danced the Charleston on the scaffolding. Back on ground level, they would compete in dance marathons, doing the polka and the foxtrot for up to three weeks non-stop. For the youth of the time, such daring hobbies reflected their devil-may-care attitude. They had survived World War I and the Spanish flu, and now lived each day as if it was their last, doing things that seemed likely to achieve that very result.

With this attitude, they shifted the boundaries. In 1924, George Mallory tried to climb Everest “because it’s there” — and he possibly became the first man to conquer this mountain. Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, Bert Hinkler and other aviators risked life and limb in their lengthy plane trips. Gertrude Ederle became the first of many women to swim the English Channel — and for a while, the feat made her the most famous woman in America.

Then there was the Bunion Derby. In 1928 it attracted 199 runners to a 3,422-mile ultra-marathon from Los Angeles to New York. After nearly three months, 55 runners approached the finish line at New York's Madison Square Garden — disheveled, long-haired, bearded, and all in agreement that mere marathons were for wimps. (The race was only held once more, the following year.)

Yet a marathon itself is still a formidable task, the pinnacle of many running calendars, and the greatest challenge that can be safely faced by most serious runner. To Sri Chinmoy, a marathon can even be a spiritual journey. "Spiritual people often like running because it reminds them of their inner journey," he has said. "The outer running reminds them that a higher, deeper, more illumining and more fulfilling goal is ahead of them in the inner world, and for that reason running gives them real joy."

It might seem to be an odd length: 26 miles 385 yards. Originally, the race had been an even 24 miles — until the first London Olympics, back in 1908. As the British Royal Family wanted their children to see the race begin, the starting line was moved back to the private grounds of Windsor Castle, while the finish line remained at the same point in the Olympic stadium. The new, official distance has been used ever since.

A minor change, you might imagine. Anyone who has run a marathon, however, knows that the extra distance can be an arduous task after running for so long. At that historic 1908 race, Italian athlete Pietro Dorando was only 385 yards from the finish line, with a comfortable lead, when he faltered, overcome by the heat and humidity. Staggering, he was overtaken by another runner, and was unable to reach the finish line without support. The extra length made all the difference.

Since then, that unusual distance has been braved by many runners, most of whom have crossed the finish line without any major problems. It is a race where the victory is in finishing, not in defeating everyone else.

But as with other races, there must be an overall winner. What makes a champion? Speed? As the world marathon record edges closer to breaking two hours, it is a useful quality, but not the only one.

Footwear? Ethiopian runner Abebe Bikila won the 1960 Olympic marathon with bare feet, unable to find a comfortable pair of track shoes. At the next Olympics, he won again, this time wearing shoes. The makers of these shoes have advertised their role in the race, as the only shoes that could satisfy “Barefoot Bikila”. (Conclusion: these shoes give you the same result as bare feet.)

Bikila's 1964 win, however, was perhaps his most surprising, as he had suffered through an appendectomy only four weeks earlier. Obviously, Bikila's greatest asset was neither his footwear nor his physical health. It was something else: determination.

Determination. American Clarence DeMar suffered from an abnormal heart and a twisted spine, which prevented him walking until the age of eight. He went on to win the Boston Marathon seven times, breaking a few world records in the process, and was known as "Mr Marathoner".

Determination. In 1996, South African Josia Thugwane was shot in the head while in his car, and only escaped death by jumping from the moving vehicle. "I thought it might not be possible for me to run again," he said. But run he did, winning the Olympic marathon four months later. I’ll say that again: Four. Months. Later.

Determination. In 1904, a Cuban postman named Felix Carvajal was determined to represent his nation at the Olympics, held in St Louis, Missouri. This was in the days before most nations were sponsoring their athletes, so Carvajal paid for his fare to America through the somewhat more humbling act of begging for money in Havana's town square.

He set off to the US, but upon arrival in New Orleans, he was cheated by gamblers and ended up virtually penniless, 700 miles from St Louis. Unable to afford a ticket, he decided to run to the Games, begging for food on the way, dressed in hiking boots, long pants and long-sleeved shirt. He made it to St Louis at the last moment, just as the marathon was about to begin.

Despite the dusty course and the 100-degree (38-degree Celsius) heat, he was all set to run the event. Another athlete convinced him to cut off his sleeves and his pant legs — but despite his lightened load, he still had to face a tough course. Out of 31 starters, 17 were unable to finish — even though the course was a mere 24 miles long.

But even after his 700-mile trek from New Orleans, the sleep-deprived, malnourished Carvajal still reached the finish line, coming fourth — and narrowly missing a medal. He gets my vote for the most awesome non-medal-winning performance in Olympic history.

But then, many have completed a marathon, already a challenging distance, in ways that made it seemingly impossible. You read of the man who did the New York Marathon in a diving bell (time: three days), the quadriplegic woman who crawled the entire distance (time: one week), and you realize that, even if you were out of shape, even if you had the flu last week, the challenge of a marathon is mostly in the imagination.

Pilgrim Runners

The archbishop is a friend of my niece.

She tells me that the archbishop walked across north Spain. For many miles he walked. For many hundreds of miles. Towards Finisterre he walked — the end of the world — where Europe ends, where the Sun sinks into the sea and all that lies further west is darkness and unknown and oblivion, death, dissolution and the unmaking of all we know.

He walked not from necessity, and he did not do it for pleasure nor in the manly pursuit of simple physical exertion. He was on a pilgrimage.

A pilgrimage! How quaint and anachronistic in our splendid twenty first century you may think. Almost as quaint and anachronistic as being an archbishop you may think.

But the archbishop is a man of prayer, and, when he had reached Santiago de Compostella — the goal of his pilgrimage, just short of Finisterre — and had knelt before the grave of Santiago (Saint James the Greater, disciple of Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ of God), when he had seen the great botafumeiro swinging out the clouds of the incense of lasting adoration, had worshipped God with thanksgiving at the Mass of the Pilgrims; he commented that he had found in the utterly mundane and earthly rhythm of walking something of a more heavenly nature, some means of entry into a prayerful and meditative state deep within the recesses of his heart.

*******

We sit on the bus in the dark of early morning in the car park by the clock tower in Kaitaia, in the wild, far-north of New Zealand. The race director climbs on board and begins to pray. I do not speak Te Reo Maori and yet I feel the power of his incantation. We are not in some grand basilica hallowed by a millennium of prayer and expenditure — we are in a rickety bus in the car park across from the liquor store in Kaitaia, but it seems that this evocation of the realm beyond the mundane is an apt start to a pilgrimage.

Having prayed his karakia, the race director gets off the bus and we begin our drive to the starting point of the race at the bluff two thirds of the way up Te Oneroa a Tohe, the wide and flat and seemingly endless beach of Tohe.

*******

I do not doubt that, as some people tell us, there are subtle powers and forces and currents that operate in the cosmos at large and in the earth of which we are generally unaware (we are generally unaware of a great many things); forces that flow through the earth, that flow and weave and interact in ways of which we may not be consciously aware.

Hannah Green in her little book which so delighted me when I read it — Little Saint — the book I wish I had written myself — writes of places in France — springs and stones and shaded valleys — which have for millennia been perceived as sacred. Today they may be associated with the blessed Virgin Mary or some other saint, but in earlier times different names and forms of sacred reality were appended to these same places. Hannah Green writes of these places as points of the earth where mysterious forces converge or flow in some particular fashion. At some intuitive level people have perceived this power in the landscape and have considered them as sacred places in whatever tradition they live their lives.

“Here, deep and enfolding, the waters flowed, the source and the little streams, the Ouche and the Dourdou, filling the air with the sounds of falling water rushing like the sounds of thousands of hands clapping, clapping as they would, in waves of applause down through the ages, as the sun and the moon and the stars in their turn moved slowly across the sky; and there seemed to be in the rhythm of the seasons, in the growth, in the life, in the very green of the place through the long summer, some secret — as if (as is the case, I have come to think, in other holy places, too) something in the conformation of the earth has preserved since the earliest days the mysterious energy of God’s presence somehow concentrated, so that in these places, as here, it, His presence or whatever it might be called, can be felt as spirit-energy in the mystery of the earth and in its beauty, but it is something more than beauty that dwells in these places.”

Hannah Green’s book deals with the village of Conques — a place long seen as such a location of spiritual power. If the archbishop had started his pilgrimage in France, he would have passed through Conques — it was long a famous stopping point on the pilgrim route to Santiago de Compostella.

I have long felt the bluff two thirds of the way up Te Oneroa a Tohe — a feature of the landscape that does not even seem to be significant enough to warrant an official name and goes rather only by its local designation: ‘the bluff’ — to be such a place as those to which Hannah Green refers where the mystery of God’s presence is preserved. It is not some lofty peak nor serene mystic lake — it is just a small rise in the land above the beach and a few rocks jutting into the sea about 63 kilometres north of the small settlement of Ahipara and yet I feel its power.

And it is the starting point of the Te Houtaewa Challenge — a 63-kilometre race along the beach to Ahipara.

Fifteen times I have stood at ‘the bluff’ in the early morning to begin the Te Houtaewa Challenge. Each time the runners have prayed with bowed head before the celestial cupola of the sky and all the myriad powers that inhabit it and the land beneath and the sea, which — endless as God — calls to us from the west — and have begun there our running pilgrimage south.

*******

‘Tipai’ the northern tribes call them — the scallop. When Sandro Botticelli — the great adept of esoteric meaning — in 1486 painted Venus rising from the froth of the breakers and stepping from a scallop shell onto a beach in Cyprus, he drew upon millennia of symbolism.

The scallop shell — within its mineral carapace: uterine secrets; within its stone tomb: life. And consider its shape. The Sun in dying each day sinks into the sea off the western coast of Spain, sinks down over the very edge of the world in a nimbus of golden crepuscular rays. The scallop shell, in solid calcium, has the same shape. And we know that the Sun sinks only to rise again, just as Santiago’s divine Master arose from His stone grave.

The sign of the scallop shell became, in the Middle Ages, the sign of Santiago and of the pilgrimage made to his tomb in northern Spain. Pilgrims wore the shell and followed signs marked with the shell.

Centuries later the archbishop followed the scallop-shell signposts all the way to Santiago. Perhaps he wore on his hat or slung around his neck like a taonga in his distant antipodean native land the treasure of that land through which he trudged — the shell of the scallop.

*******

When the first Europeans arrived in their large wooden sailing canoes in our bright antipodes, they quickly realised they were in a new and strange world. Amongst the many strange things they discovered was the fact that the royal and heraldic swans that they knew in their dear homeland, white of feather and regal of eye, were not to be found here. Rather, upon the waters they saw creatures from their own infernal mythologies swimming in placid reality — black swans long believed to exist only in the dark imaginings of stories of hobgoblins and doomed princesses. It seemed they truly had arrived in a land of the Anthropophagi, of headless monsters with eyes and mouths on their chest, of one-legged dwarves in the habit of lying on their backs to protect themselves from the sun in the shade of their one foot.

*******

There may be those who think that running 63 kilometres along an empty, desolate beach would be no more eventful and engaging than a marathon down a hospital corridor. They are wrong. A thousand tiny variations mark and enliven one’s progress: the bubbling holes of underground creatures, a slick of plankton, mysterious objects cast up from the ocean’s depths to dry and decompose upon the land, a change in the heave of the sand hills, a new crash of waves, a cloud, a burst of enervating sunshine, the flicker and interchange of clouds and sun upon the sand, a new texture, a new pattern upon the sand wrought by the eternally variable sea and wind. Shells and driftwood and a dead seal, fish and fishers, birds that swirl up or swoop down, the hill of sacred fire glimpsed through haze.

*******

Scattered down the length of the beach — scattered by the casual flow of the sea and the chances of life and death and seagulls — as guide to us on our pilgrimage — our pilgrimage not to Santiago and the end of the world but to Ahipara and the sacred flame that gives it its name and is never extinguished — there lie — as sureas the signposts raised in Spain by diligent local authorities — shells: the shell of the scallop.

But here the scallop shells on the sand are not that colour so aptly named ‘sea shell’. Here the shells are black, black as the mysterious, inverted swans of our antipodean realm where men walk upon their heads and the birds fly upside down and all is new and all is possible.

I follow the black shells. I think of the archbishop. I think of my niece. I think of eternal running, of a pilgrimage beside the sea, beneath the illimitable sky that lasts forever — an eternal pilgrimage to an eternal goal.

Perhaps I shall never kneel beside the tomb of St James but I shall follow his shells along the beach always.

Race Prayers

I moved to New York from Philadelphia in the autumn of 2000, to be closer to my spiritual Master, Sri Chinmoy. Maybe the best way to really understand a spiritual Master’s philosophy is spend a lot of time in his company. I mean real Gurus like Sri Chinmoy actually live their teachings, so if you want to learn how to apply meditation to everyday life, then the best thing to do is to associate with them as much as possible. For almost ten years I was able to spend many hours a week in the company of the Master. We would usually meet twice a week, either on Wednesday evenings at a big public elementary school on Parsons Boulevard, or, on weekend afternoons, at a “tennis court” on 164th street that did double duty as a meditation sanctuary.

Also, on Saturday mornings we held two mile “Runners Are Smilers” races around Jamaica Public High School. Had the races been held on the actual Jamaica High School track, my prayers would have been answered and my life would have been a lot easier. But no, we would run on the pavement around the school, and the course included a monstrous hill. Had the course been reversed, the hill would have been turned into a water slide of comfort and ease, but then how would it served as good “training”?

Anyway, I usually led the pack for the first one sixteenth of the race, and then I would almost always finish dead last. I didn’t mind being last actually. I never put a lot of pressure on myself; my goal was just to try to be in a nice consciousness and to do the best I could. Often, when I was running and struggling alone, Sri Chinmoy would pass by in Vinaya’s car. He rarely looked at me directly that I noticed, but still I felt his palpable, loving encouragement.

I did, however, always desire to finish strong. So for the last two or three hundred meters, which included the uphill section on 168th street, I would push myself to the absolute limit. When I gave it my all, I would try to be in tune with my own spirituality, with my Master’s blessings. At that time, I felt that I wasn’t showing off, but I did feel I was able to run faster and better just because I was in a prayerful consciousness.

Often, our Saturday morning races would be won by Jason, a young Black man with long dreads who lived in the area. Interestingly, he never wore running shoes, but instead chose heavy cross trainers more suited to shooting hoops.

I had an intense rivalry with an older man who I called my running “arch-nemesis”. For a long time he had a serious knee injury, and he would speed walk while I would run. Usually I was able to beat him. But, then he recovered from his injury and I never beat him again!

Once there was a terrible blizzard and only two runners showed up. I chose to stay home and sleep that morning, but had I participated, I might have actually placed!

Interestingly, Sri Chinmoy waited a long time for almost everyone to finish before he would hand out prasad. Often he would dictate a spontaneous prayer which he would compose on the spot. I remember standing with the other runners, all of us sweaty and exhausted, holding little notebooks and looking at the Master as he put his index finger to the corner of his mouth and meditated for a few seconds, receiving the poem whole cloth from the infinite Unknown. Then he would start speaking, sometimes haltingly at first, but then with utmost confidence and authority:

Alas, because of our teeming self-doubts

The immense and intense beauty

Of our morning hearts

Cannot come to the fore

And bloom and blossom.Mornings come to me

With the sound-power of the Unknown.

Evenings come to me

With the silence peace

Of the Unknowable.

My Lord Beloved Supreme

Comes to me

Both in the mornings

And in the evenings

With what he has

And with what he is:

Concern.In the morning

I am the blossoming beauty

Of God.

During the day,

I am the unending Duty

Of God.

At night,

I am the dreaming melody

Of God.—Sri Chinmoy, My Race-Prayers

In many of his “Race Prayers” I noticed a contrast between morning and night, bondage and freedom, darkness and light. It was as if, by running, just running, we were affirming our own divinity and acting as warriors in the battlefield of life. Incidentally, Sri Chinmoy always offered me tremendous and generous encouragement in my running. He didn’t care I was a pathetic runner par excellence. He appreciated the fact that I was willing to run in spite of not having a lot of talent for it. It reminds me of a poem by Tagore that Guru often quoted:

To the birds you gave songs,

The birds give you songs in return.

To me you gave only voice, but asked for more,

And I sing.

Sometimes when I am perplexed, or doubt my life-decisions I go running. To run is to at least do something. Whenever I run I feel a solid sense of accomplishment, even if I’ve just run for a half mile. I like running as a symbol of overcoming self-doubt and ignorance. Aside from the profound meditation-experiences that I have had with Sri Chinmoy, running has done most to inspire me to challenge my hurdles and to make progress. It really is a powerful metaphor, which is why Sri Chinmoy gave it so much importance.

I remember we would actually take prasad from the hood of Sri Chinmoy’s car. Often the prasad consisted of sugar wafers or vanilla Oreo cookies. Sri Chinmoy would often look at each runner in the eye and give us a sweet smile. After we had all taken prasad, Sri Chinmoy would sit in the car in silence for a minute or two and meditate. Then he would bow his head and the car would drive off. After that, we would all run in little packs to our respective apartments and get ready for the day. What a wonderful way to start a Saturday. How much joy I get in remembering those days!

Writing & Poetry

More stories from Sri Chinmoy's students.

My inner calling

Purnakama Rajna Winnipeg, Canada

Filled with deepest joy

Tirtha Voelckner Munich, Germany

It does not matter which spoon you use

Brahmacharini Rebidoux St. John's, Canada

A Quest for Happiness

Abhinabha Tangerman Amsterdam, Netherlands

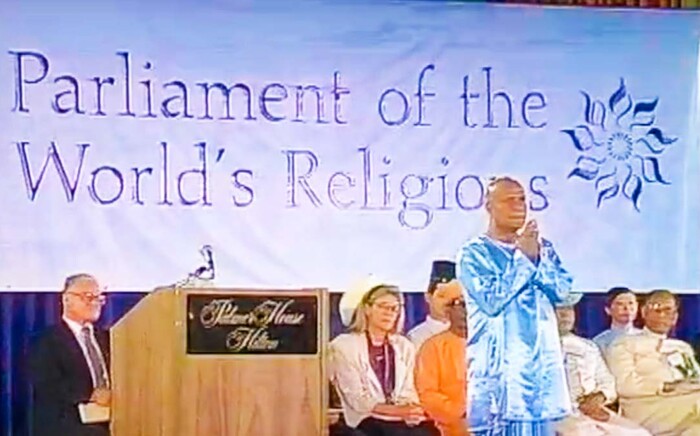

Sri Chinmoy's opening meditation at the Parliament of World Religions

Pradhan Balter Chicago, United States

A Flame in my Heart

Adesh Widmer Zurich, Switzerland

I was just so transported by the atmosphere

Pulak Viscardi New York, United States

The most beautiful and fulfilling of all possible experiences

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

People see something in Guru and want to be part of it

Saraswati Martín San Juan, Puerto Rico

You only have to keep your eyes and ears open

Gannika Wiesenberger Linz, Austria

The connection between Sri Chinmoy's music and my soul

Kamalakanta Nieves New York, United States

The spiritual life is normal to me

Shankara Smith London, United KingdomSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

How Sri Chinmoy appreciated enthusiasm

Prachar Stegemann Canberra, Australia

Getting through difficult times in your meditation

Banshidhar Medeiros San Juan, Puerto Rico

2 things that surprised me about the spiritual life

Jayasalini Abramovskikh Moscow, Russia

Siblings on a spiritual path

Pranlobha Kalagian Seattle, United States

Why we organise ultra-distance events

Subarnamala Riedel Zurich, Switzerland

My daily spiritual practises

Muslim Badami Auckland, New Zealand

Meditation functions with Sri Chinmoy

Kokila Chamberlain Bristol, United Kingdom

Except where explicitly stated otherwise, the contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. read more »

SriChinmoyCentre.org is a Vasudeva Server project.