A Flame in my Heart

My real spiritual awakening I owe to my father, who gave me Hermann Hesse’s book Siddharta to read when I was 15. This is the story of a Brahmin boy in India who leaves his home, joins a group of ascetics and lives in the desert. He meets Lord Buddha but is not satisfied with Lord Buddha’s path. Finally, he finds his Guru and realises God. When I read that book, I immediately knew that my life would be a spiritual quest. I read the Koran, the Bible and books about Buddhism – but for me the most striking book was the Bhagavad Gita. This book I read over and over again.

When I was between 18 and 22, I tried to meditate and juggled a little with trying to develop occult power. Most importantly, I came across Indian classical music. In 1976, my wife Ajita and I made a five-week trip to India, visiting several Ashrams with the hope of finding our Guru. We went to Rishikesh and to the Ramana Maharshi Ashram in South India. Our last stop was the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry. We could not enter the Ashram but were told to go to Auroville, which is about 7 kilometres outside Pondicherry. There we slept in a straw hut with rats running about in the roof, looking down at us during the night. The next day we fled from the place and went back to Delhi, where I decided to become a music teacher. I felt some kind of power inside myself and had the urge to give something to humanity.

In Delhi we visited a music store, where I held a sitar in my hands for the first time. The touch and vibration of the instrument affected me deeply, and I decided that I had to learn this instrument. A few months later, back in Switzerland, Pandit Ravi Shankar gave a concert in my home town. I had my first spiritual experience during this concert. As we were leaving the concert hall, we met Abarita, who was outside distributing leaflets for a meditation class, which Ajita and I attended.

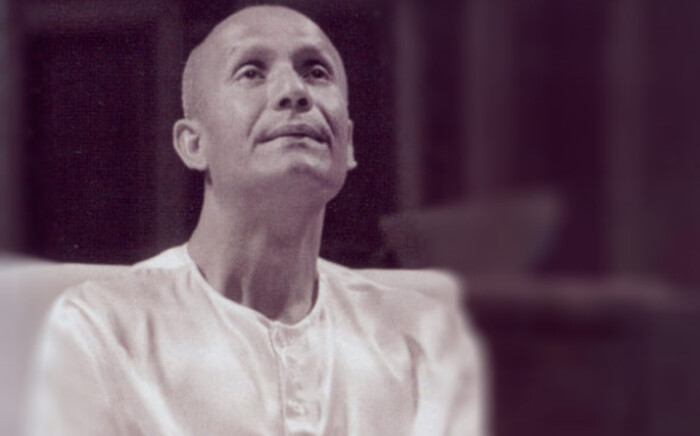

Abarita showed a film of Sri Chinmoy in samadhi1 and talked about meditation and Indian culture. I felt that I knew more about Indian culture than Abarita because I had visited India a few months earlier, whereas Abarita had never gone to India. So my pride came to the fore, not allowing me to see and feel Guru’s light. Nevertheless, we went to the Sri Chinmoy Centre in Zurich for a meditation. There we saw Guru’s Transcendental meditation photograph2, but nobody explained anything, and there were no books, nothing. I looked at the Transcendental photograph but did not understand what it was all about. So we did not become Guru’s disciples at that time.

During the year 1977, I was torn with the desire to have a spiritual Master but with no idea of how to find one. At the same time I bought my first sitar and felt tremendous joy in experimenting with the instrument. Ajita and I decided to go to India to learn Indian classical music, with the intention of realising God through music. Then we were unable to get visas for India, so we decided to go to Sri Lanka.

In December 1977, we flew to Sri Lanka to learn Indian classical music from the best musician in the country for the next four years. In the beginning I still had my God-realisation in mind, but as I became more and more absorbed in the process of studying and practising music for many, many hours each day, I forgot about my spiritual search.

After four years, I realised that I would never be able to really play Indian classical music, and that I would just be fooling both the audience and myself if I were to announce myself as an Indian musician back in Europe. So we stopped studying music and started a programme of social education in Switzerland to address the heart-wrenching poverty that we had seen in both Sri Lanka and India. We wanted to go back to India one day to start an orphanage. The programme that Ajita and I started was a very good medium for self-knowledge and self-discovery. My inner urge for a higher life had once again been awakened, and I felt that "the real thing" was still missing from my life. My brother-in-law had had a Master for several years, and since I did not know of anybody else and was desperately in need of a spiritual Master, I wrote to his Master and applied to become his disciple. On his path, the diet is very strict; his students have to avoid not only meat and fish but also eggs.

Having been vegetarian already for many years, this did not seem to be a problem for me. However, because I was working and partly living in a home for deprived children, I wrote on my application that, due to my job, it would be too difficult to avoid eggs completely. I received the reply that I would not be accepted if I continued to eat eggs. I was desperate.

To complete my three years of music school, I was required to write a thesis. The subject of my thesis was music therapy using the tamboura, an Indian instrument. I wanted to try this therapy with one of the children in the home for deprived children where I worked, but I had no instrument. It was now 1986, 10 years after meeting Abarita outside Ravi Shankar’s concert. I remembered that Abarita was dealing with Indian instruments, so I called him and asked whether he had a tamboura for me to buy. In the meantime, Abarita had set up his tofu factory and no longer had anything to do with Indian instruments. But he gave me the phone number of someone in Madal Bal, who agreed to purchase a tamboura for me. I was to pick it up from the Madal Bal health food store in Zurich

On this day, 2 January 1987, Ajita and I were still living in Appenzell, about 100 km away from Zurich. Our whole family, with Anupama, two years old, and Bandhavi, six months old, travelled by train to Zurich to visit the shop at Kreuzplatz. Gunthita was working in the shop. The tamboura was sitting there in one corner. I picked up the instrument and tried to tune it, but somehow I was not able to. I wondered what possibly could be wrong, as tuning the tamboura should not have been a problem for me. However, I simply could not tune it. I thought, well and good, let’s do it the Indian way and give it a little time. So I placed the tamboura back in the corner and looked around the tiny shop.

There were many pictures of Sri Chinmoy, but one picture immediately struck me. Guru looked so happy in this picture and immediately made me jealous. Here was definitely somebody who had really found his goal, who was satisfaction incarnate. And I was not!

A recording of Gunthita’s music group (named Fountain-Light at that time) was playing in the shop. I went back to the tamboura, and lo and behold, it was in tune. It was in tune exactly with the music that was playing. At that point I knew something was happening. I remember looking deep into Gunthita’s eyes, searching for something special. But she just looked back at me with her open, cheerful eyes. I remember also buying one of the books that were for sale. The most important thing was that I felt Guru’s light in my heart like a tiny candle flame – it was such a nice, warm, loving feeling.

Before leaving the shop with the tamboura, I asked Gunthita how to become Guru’s disciple. She explained that we would have to send in our photos with an application. After leaving the shop, Guru’s flame in my heart kept on burning. When I returned home, I sent my picture and application, and about a month later, I got a call saying that I was accepted as Guru’s disciple.

About the author

Adesh Widmer

Adesh Widmer performs concerts of sitar improvisations based on Sri Chinmoy’s melodies all over the world. Adesh’s style is very meditative; the listener is led into the spontaneous flow of meditation.

Performance of Adesh (sitar) and his wife Ajita (Tabla), performing live in Zurich as part of the Songs of the Soul concert series.

Play VideoA recording of Adesh's album 'Joy of Sitar', where he plays Sri Chinmoy's melodies.

First steps on the spiritual path

More stories from Sri Chinmoy's students.

So much longing, for something

Pushpa rani Piner Ottawa, Canada

Our Guru becomes the perfect disciple

Devashishu Torpy London, United Kingdom

The connection between Sri Chinmoy's music and my soul

Kamalakanta Nieves New York, United States

Why run 3100 miles?

Smarana Puntigam Vienna, Austria

You only have to keep your eyes and ears open

Gannika Wiesenberger Linz, Austria

Failures are the pillars of success

Anugata Bach New York, United States

“Where there is heart, always there is a way.”

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Sri Chinmoy performs on the world's largest organ

Prachar Stegemann Canberra, Australia

How I learned from Sri Chinmoy

Pradhan Balter Chicago, United States

I just knew from the moment I saw him

Ashrita Furman New York, United States

The very first time I heard about my spiritual Master

Banshidhar Medeiros San Juan, Puerto Rico

If a wish comes from the soul, it will be granted

Kamalakanta Nieves New York, United StatesSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

The greatest adventure that you can embark on

Mahatapa Palit New York, United States

Growing up on Sri Chinmoy's path

Aruna Pohland Augsburg, Germany

Meditation functions with Sri Chinmoy

Kokila Chamberlain Bristol, United Kingdom

'Everyone is feeling nothing but love'

Suren Leosson Reykjavik, Iceland

Sri Chinmoy's inner guidance

Kailash Beyer Zurich, Switzerland

When I met Sri Chinmoy for the first time

Baridhi Yonchev Sofia, Bulgaria

The relationship between Guru and disciple

Baridhi Yonchev Sofia, Bulgaria

Except where explicitly stated otherwise, the contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. read more »

SriChinmoyCentre.org is a Vasudeva Server project.