Inspiration-Letters 3

Science Issue

Of Saints And Rabbits

by Barney McBrydeSometimes a man gets to thinking . . . to musing. . . to mulling things over. . . and it generally ends in a painting.

I spent Christmas with my parents.

Lying under a tree, the clink of ice in a tall glass at your elbow, reading Harry Potter – perfect. “So it is Dumbledore who dies!”

When not lazing about, I chanced upon a photograph in the cupboard in the lounge - a photograph of a painting I had produced during an earlier Christmas break. It set me thinking.

Remember Ronald Lockley who wrote the seminal study on the behaviour of the wild rabbit? How I loved that book as a kid! He also wrote a number of autobiographical books. One was called The Island – about his days living alone on an island off the Welsh coast. How that appealed to me too!

Generations have read potted versions of Robinson Crusoe – never mind all Daniel Defoe’s biblical musing, we all just want to hear the story of a man living on an island. It seems that the man on the island must represent some deep-seated human aspiration – why else is he so appealing? Is he not in fact a symbol of the individual’s withdrawal into himself? Is he not, like the monk in his distant cave, the image of one who has withdrawn from the mundane life to know himself?

What we can forget as we think of the actual man on his physical island, is that at any time we can ourselves withdraw to the inner island, and, like Defoe’s Crusoe, there in the silence and peace, free from all distraction provided by those parts of our own nature which bustle about on the mainland, we can read the inner scripture – we can listen to the silence speak. The man alone on his island is the image that expresses that.

In 1997 I visited my brother in Germany. One day he took time off work and we went on an adventure to Maria Laach and Schloss Burreshheim. We were driving along the banks of the Rhine when Michael pointed out to me an island in the river. On the island stands a convent. The story goes, he told me, that in the days when Europe was emerging from the Dark Ages, the great hero Roland – glittering star of Charlemagne’s court – fell in love on the shores of the Rhine with Hildegunde, the daughter of a local prince. Later, when he had been called off to slaughter his fellow man in Spain, word came to Hildegunde that he had been killed in battle. By the time he actually returned to Germany to exclaim, as Mark Twain was to do, “the reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated”, it was too late. One account puts it thus:

“Hearing of Roland’s death, for days on end Hildegunde shut herself up in her little bower, and even her father’s gentle sympathy could not assuage her bitter grief. Weeks passed. Then one day the pale maiden entered the knight’s chamber, her grief quite transfigured. A last great convulsive sob had torn her lover’s name from her heart, had quenched the flame of sorrowing love for him, and now her soul was to be filled ever with the holy fire of the love of God.”

She withdrew to the island in the river and never spoke to Roland even on his return. How could she? She had found the island within – solitary, self-sufficient, separated from the world by the deep, placid waters of her own contemplation, unswayed by the allure and hubbub of the mainland.

The image stuck in my mind.

A few weeks later I was in Budapest marvelling agog at the glories of the Matyas Templom and weeping at the tomb of Gul Baba.

I have a certain dislike of museums but the Museum of Budapest History was undergoing alterations and so entry was free – I entered . . . and enjoyed it a lot. It was here that I learnt about the island in the Danube at Budapest called Margit Szegit – Margaret Island.

Margaret, born in 1242, was the daughter of King Bela IV of Hungary but spent her whole life in a convent. From the age of ten till her death at age 28 she lived on the island in the Danube that now bears her name.

Here again was the woman on the island.

The thing that I found out at the Museum of Budapest History which appealed to me most was that prior to Margaret’s arrival in 1252, the island was obviously not called Margaret Island . . . it was called Rabbit Island.

*

People often question the origins and symbolism of the Easter Bunny. The oft-cited rather basic fact that Easter is about new life and rabbits reproduce quickly is not in fact entirely true.

Before Ronald Lockley carried out his ground-breaking study of the behaviour of the wild rabbit, the strange fact is that very little was know of the life of this ubiquitous creature. Rabbits are crepuscular – being active at dawn and dusk. What nobody knew before – because nobody had bothered to look – was that they are also nocturnal, hopping about in the dark when no humans are there to see.

However, the idea that rabbits were only active at dusk and dawn lead our medieval forebears to conceive of the rabbit sitting patiently in his hole awaiting the rising of the sun, sitting in faithful expectation and hope for the return of the light. The rabbit thus became an image of Easter – not of Easter Sunday, but of Easter Saturday: of the Christian waiting in the darkness of Easter Saturday for the light and effulgent grace of the resurrection on Easter Sunday. As the rabbit waits faithfully and with sure hope for the dawn, so too we wait for the dawning of divine grace in all its forms – the sort of preparatory waiting one might best accomplish free from the distractions of life – like . . . on an island perhaps.

When I got back to New Zealand, these, and other, ideas coalesced into a painting – the photograph of which I just found in my parent’s cupboard.

The painting itself sold about five minutes after the exhibition it was part of opened. It sold under the dignified and elusive name I had given it in the catalogue – “Budapest 1997” – but to me it had always been and would remain – “Maggie and the Easter Bunny”.

Barney McBryde Auckland - New Zealand

Research And Revelation

by Shane MageePeople often ask me if I find a conflict between my research in particle physics and my interest in meditation and yoga. I would answer by pointing to the lives of the great scientists, who braved tremendous opposition in their quest to offer the world new truths, new insights into the nature of reality.

Meditation is not an escape from the world! It is a way, rather, to explore and understand ourselves, and by extension, the world.

I look upon my work in physics as an opportunity to overcome barriers in my spiritual life. Patience is one thing I need more of; the ability to persevere in work without getting attached to its outcome is another. And in the field of particle research you need to develop both of those qualities if you're to stay in the game. After all, results in particle physics have a time-scale of their own, almost wholly independent of how much you push or shove to get them.

Science, in its own right, is a spiritual path of sorts - it may not necessarily lead to the top of the mountain, but the people in that path search for Truth in their own way, and are basically aiming to expand their horizons as best they know how. The same yearning spiritual aspirants have to understand why we're here and what's our purpose is aflame in their hearts too; it's just that they still think the mind holds all the answers.

Or do they? The people on this 'path' of science can essentially be divided into 2 main groups: the rishi-scientists who change the way we view the world (of which in the entire history of mankind there have perhaps been about 20), and then the rest of us who fill in the gaps and do a spot of tidying-up here and there once this new world view has been handed down. The former group are, of course the Newtons and Einsteins, the ones we draw the inspiration from when we look at the world of science, and their accounts of their discoveries invariably have this tinge of divine revelation about them, the sense that their discovery was an uncovering of a higher Truth that had always lain there.

For example, consider this: The modus operandi for great scientific discoveries seems to be to strain and strain yourself searching for the answer until it almost kills you (and in doing so preparing the mathematical framework to assimilate what you are about to receive), and then give up and go for a spot of hiking in the mountains, or something similiar. The French genius Henri Poincaire would describe such a process and then recount how the answer came to him as he was stepping off a bus. Einstein always shaved very slowly in the morning, wary of repeating one particularly bad experience where the Truth burst in on him unannounced. Another great scientist, Wolfgang Kohler, when asked the formula for great discoveries replied -and I’m definitely paraphrasing here-, "Bath, bed and bus." Richard Feynman would describe experiences of floating around in complete bliss for four days after a major breakthrough, which apparently happened to him three times. Is 12 days of bliss enough return for a lifetime of slavery? I’m not sure!

Sri Chinmoy believes you can draw inspiration from different paths as long as you maintain one-pointed concentration on following your own path and don't try to put a foot each in two different boats, as he would say. In my search for the highest Truth, I already have a path, and I'm sticking to it. But when I take my physics research not as a search for Truth in itself but as a golden opportunity to progress in my spiritual life - that's where the satisfaction lies.

This essay was inspired by postings on the Sri Chinmoy Inspiration Group

Shane Magee Dublin - Ireland

Economics - "The Dismal Science"

by Tejvan PettingerIt is debatable whether economics should actually be defined as being a science. A science like math or physics usually gets its satisfaction from proving something to be irrevocably true. Solve a complex equation and QED that’s the answer, there’s no argument. Economics on the other hand will rarely give us a simple answer. Ask 5 economists a question and you’ll get 6 different answers.

Yet economics could make claim to be a science even if, as John Ruskin disdainfully called it “…the Science of getting rich” (Ruskin 1). Over the years economics has also managed to adopt the equally unflattering label of “the Dismal Science” - perhaps fitting for a subject where even the leading theorists can fail to agree.

We could say economics began as soon as hunter men began to exchange their captured prey with other cavemen. But generally the science of economics did not begin to be formalised until fairly late. However, over the past two centuries, the science of economics has seen no shortage of colourful characters all offering their solutions and diagnoses of the economic problem. This is a small selection of some of the economists who have shaped the subject (for good or ill).

The Dismal Prophecies of Malthus One of the first economists to proffer his theory was T.Malthus. Malthus is chiefly remembered for his essay on population. In this essay, Malthus argued the human race was doomed because the population was increasing at a faster rate than our capacity to grow food. In many ways Malthus was one of the earliest proponents of “The End Is Nigh” syndrome, and unsurprisingly it was Malthus who claimed for economics the label “The Dismal Science”. Fortunately, Malthus displayed a trait that many later economists would share - he was wrong. The population didn’t starve. In fact during the nineteenth century the forces of capitalism flourished creating unprecedented wealth- at least for those who owned the means of production.

Adam Smith - The Invisible Hand One of Capitalism’s strongest exponents was the economist Adam Smith. In his book, The Wealth of Nations, Smith claimed that if people followed their own self interest, then these individual acts of selfishness would have the remarkable effect of leading to the greatest overall benefit for society. This is the basic principle of the book, although Adam Smith did take 1,260 pages to say it (unfortunately, very few economists have ever learnt the art of being concise). Adam Smith has thus become synonymous with support for free market economics. However, many people forget he was rather a modest Scottish intellectual who became chair of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University (Smith’s other major work was about charity and ethics but it is for his articulation of free market economics that he is chiefly remembered). His seemingly paradoxical argument about the free market has remained at the centre of all major debates in economics. Is an unbridled free market really the best economic system? Nevertheless, even the most ardent free market economist cannot ignore the fact that capitalism creates inequality and in the nineteenth century this inequality was painfully evident. Thus, many economists came along to challenge the free market ideologies of Adam Smith.

Karl Marx - The Revolutionary Economist Whether deliberately or not Karl Marx was destined to play a major role in world history. Basically, Karl Marx was of the opinion that the inequality of capitalism would inevitably lead to a revolution by the oppressed workers and the formation of a Communist state. In fact Karl Marx went to extraordinary lengths to explain this principle. His most important work, Das Kapital, could make claim to be one of the most boring books ever written (perhaps only beaten by Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus). However in F.Engels, Marx had a companion who was able to help romanticise the ideals of Communism. But despite the various attractions of Marxism, it never really took hold in the US and Western Europe.

J.M.Keynes - The Greatest Economist? Mainstream economists were, before WWII at least, fully entrenched in the free market orthodoxy of classical economics. Just to reiterate, these economists differed little from the original ideas postulated by A.Smith, who held that the free market would create wealth and prosperity. All problems would invariably be solved by the inexorable workings of the “invisible hand” of the market. However in the 1930s free market economics faced a seemingly impossible challenge – The Great Depression with its mass unemployment, bankruptcies and falling output. In the face of such economic hardship the appeal of radical alternatives created serious political turmoil - Western democracy itself was threatened. But many economists stuck to their ideology arguing in the Long Run everything would be OK.

It was thus in the middle of the Great Depression that J.M.Keynes rose to prominence, retorting to orthodox economists: “In the Long Run we are all dead”. Keynes saw no point in waiting a couple of decades for the Depression to come to an end. He argued for immediate government intervention and, in particular, he called for the government to spend, spend, spend.

John Maynard Keynes was born in 1893, which was the year that Karl Marx died. Both Marx and Keynes were to write influential critiques of the Capitalist system but here the similarities end completely. Marx was a rather angry loner, many of his enterprises failed and much of his life was spent working anonymously in the British Library. Keynes in many respects was very different; he cut a dashing figure - a brilliant economist, who could also mix with the elite of British society. Keynes attacked the inequities and insufficiencies of the free market but that didn’t stop him from making a small fortune by speculating on the foreign exchange markets. Keynes was also a visionary: While the Allies were clamouring for a victor’s peace at Versailles in 1919, Keynes resigned from the British delegation. He argued the reparations imposed on Germany would be impossible to repay and that they were a recipe for the humiliation of Germany and future problems. His book The Economic Consequences of the Peace became a best seller and in retrospect proved to be a damning indictment of the narrow-mindedness of the allied victors.

Keynes was brilliant at many things and he knew it. Once he was placed second in an economics exam. His only reply was that:

“That shows I know more economics than the examiner.”

Keynes didn’t just restrict himself to economics; he wrote a book on mathematical philosophy (highly praised by Bertrand Russell). He was also a leading figure in the Bloomsbury group of leading artists, poets and writers. Keynes later even opened his own theatre, which like most things he tried his hands at, proved a great success. Keynes was no socialist but this didn’t stop him from poking fun at free market economists. In direct challenge to the optimistic assertion of Adam Smith, Keynes took a different view.

“Capitalism is the astounding belief that the most wickedest of men will do the most wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone.”

This shows Keynes at his best - happily attacking orthodox views with a panache and confidence that was hard to resist. Keynes may have had many human weaknesses but he was able to brush these aside with his evident genius and enormous capacity for innovation and radical ideas.

It was the effects of the Great Depression that led Keynes to his greatest work. He scoffed at the orthodox free market economists who said the government should do nothing in the face of mass unemployment.

Keynes’s strategy was for the government to intervene, borrowing if necessary. This would create jobs, which would give income for others to spend thus creating more jobs. A deceptively simple idea, but too radical for western governments who were unwilling to borrow. Unfortunately it wasn’t until the onset of the Second World War that employment increased to pre 1929 levels. By the end of the war Keynes was given high regard and he was put in charge of the economic planning for post-war Europe. Unfortunately on achieving worldwide fame he died untimely at the early age of 62. However he has left a profound mark, helping to create a whole sub section of economics (Macro Economics)

About the Author - R. Pettinger (part time economist) I studied Economics at Oxford as part of a degree in PPE. I enjoyed the course immensely. Graduating with a 2:1 degree I made the natural career progression and got a job as a gardener in the grounds of my Oxford College, Lady Margaret Hall.

I was quite happy pulling up weeds in the beautiful gardens but later economic realities made me look for a job with greater fiscal remuneration. Thus I got a job as a part time Economics teacher and have since gone on to teach Economics to A Level students aged 17-19 for the past 6 years.

When people hear I’m an Economist they often they display great enthusiasm that I will be able to solve their financial problems. Alas, this is a false hope. Economists are very good at explaining why the economy is doing badly; we can eloquently explain the causes of bankruptcy and likely economic effects. But when it comes to creating wealth we may mysteriously point to the invisible hand of the market and say all in good time. If economists were really adept at creating wealth it is quite likely they wouldn’t be spend their time lecturing on economics (Keynes of course was an exception).

Link: Economics Jokes

Tejvan Pettinger Oxford - England

Happy Birthday To Someone

by Noivedya JudderyWhen I was at school, spending my spare time devouring trivia at libraries, one of my hobbies was finding out which famous people shared my birthday. I was very excited to find that Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., was among them. Not that I knew anything about him, but I knew he was really famous, and considered a Great Man (in America at least). A few others shared my special day: dancer Cyd Charisse, actor Lynn Redgrave, author Kenneth Graham, one of the Monkees, the Skipper from Gilligan’s Island... With unbridled enthusiasm, I would read avidly about each celebrity with my birthday, whatever their claim to fame. Then I would tell everyone about their greatness: “Cyd Charisse appeared in some of the best movies ever made”; “The Monkees were a truly superb pop band”; “Gilligan’s Island was better than everyone thinks!”

Most of us are proud of our birthdays, even if they seem fairly unexciting to everyone else. Super-patriotic American showman George M. Cohan, the first entertainer to win the Congressional Medal of Honor, was perhaps disappointed to be born on July 3, 1878, missing US Independence Day by inches. But his father (also in show business) had changed George’s birthday, so that in his self-penned hit song “Yankee Doodle Dandee”, the younger Cohan could proudly sing that he was “born on the fourth of July.” The lyrics have made it sound like the birthday of true patriots, but of course, most of them were born on another day entirely. Though three US Presidents have died on that venerated date, only one (the forgettable Calvin Coolidge) had it for a birthday.

Though America was born on the fourth of July, Jesus Christ almost certainly was not born on Christmas day – previously the date of an ancient pagan ritual. But now, Christmas-born people are upstaged, year after year, by someone who, strictly speaking, doesn’t even share their birthday. They only get one set of presents each year, and as the turkey and the plum pudding are taking so much room, they don’t even get a birthday cake!

(In fact, I always considered that the best thing about my own birthday – apart from sharing it with Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. – was that it was NOT Christmas, and indeed, it was just distant enough so that my parents couldn’t use the one-big-combined-present excuse.)

But it’s worth it in the end for the Christmas-born. Not only is their birthday a national holiday, but people born on December 25 tend to lead successful lives. Studies show that this is true, though I’m not certain what these “studies” are meant to involve. The list of Christmas babies is impressive: Sir Isaac Newton, Helena Rubenstein, Cab Calloway, Rod Serling, Little Richard, Sissy Spacek, Annie Lennox…

Of course, every date has its celebrities (and I’ll bet this one doesn’t have anyone from Gilligan’s Island), but Christmas seems to be a good time to be born. Publicity for the Hollywood star Humphrey Bogart always listed his birthdate as Christmas Day 1899, which was later “exposed” as a Hollywood myth. As Clifford McCarty wrote in The Complete Films of Humphrey Bogart, Warner Bros Studios had changed his birthday from the less romantic date of 23 January 1900, “to foster the view that a man born on Christmas Day couldn't really be as villainous as he appeared to be on screen” (McCarty). Interestingly, before his roles in “The Maltese Falcon” and “Casablanca”, Bogie usually played villains.

This would have been one of Hollywood’s strangest publicity decisions. Stars were meant to fit their on-screen persona, so “softening” one of their tough guys with a Christmas birthday seems to defeat the purpose. However, as any of his biographers could tell you, Bogart was the real deal – and that included his birthdate. Bogart really WAS born on Christmas Day.

What can Christmas babies draw from this? Can they take pride in sharing a birthday with one of the great film stars? Some astrologers have suggested that each birthday has a certain personality type, and a quick glance would suggest… nothing much. What do I have in common with the celebrities, named above, who share my birthday (apart from the same star sign)?

Are birthdays as special as we think? Let’s look at people with the same birth dates – not only those born on the same date, but also the same year. Birth twins, at it were.

Start with Charles Darwin and Abraham Lincoln, two of the great figures of the 19th century. Both were born on the same day: 12 February 1812. They were born worlds apart: Darwin in a mansion, to a distinguished west England family; Lincoln in a log cabin, to a poor frontier farmer. Nonetheless, in their respective fields, they had a few things in common.

Both were raised as Christians, but Darwin died an atheist, and Lincoln was reputedly an outspoken non-believer (both were accused of being “godless”). Both had less-than-impressive school records, but self-taught themselves to reach the peak of their professions. Both were "mutaphiliacs", known for their ability to embrace change. Both detested slavery. "It makes one's blood boil, yet heart tremble," wrote Darwin, "to think that we Englishmen and our American descendents, with their boastful cry of liberty, have been and are so guilty" (White and Gribbin 57). Lincoln’s stated objective in the American Civil War was, of course, to end the slave trade.

Both men had major turning points in 1835, at age 23: Lincoln entered politics, and Darwin visited the Galapagos Islands, which eventually inspired his Theory of Evolution. His greatest work, The Origin of Species, was published in 1859 - one year before Lincoln was elected US President. With these events, both would challenge the status quo - changing the world, and winning enemies among the conservatives of the time: Darwin would be denounced and Lincoln would be killed.

In those days, when celebrities did not grow on trees (at least, not to the same extent as today), it seems remarkable that two such outstanding figures were born on the exact same day. According to astrologers and numerologists, however, it is no coincidence.

Whether or not you believe in astrology, there is statistical evidence to suggest that, yes, birth twins tend to have a few things in common. In the seventies and eighties, French psychologists Michel and Francoise Gauquelin studied the birth charts of over 60,000 people, and found that people with similar birth charts seem to have similar character traits and professions (Watson). Independent researchers had the same findings, using different samples. Even sceptics’ groups had these findings, which must have caused them no end of frustration.

In the world of showbiz, people are often matched up due to their astrological compatibility. I’m not sure whether this works, but some birth twins, at least, have proven very compatible. Daniel Day Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer made good co-stars in the 1993 film The Age of Innocence. Quincy Jones composed the music for the classic 1969 flick The Italian Job, starring his birth twin Michael Caine. Oliver Stone directed Tommy Lee Jones in their two most controversial movies. And a 21 June 1947 birthdate would have helped you win a starring role in Family Ties. (Meredith Baxter and Michael Gross played the parents in that 1980s sitcom.)

Then there are environmental artists Christo (Javacheff) and Jeanne-Claude (de Guillebon), both born on 13 June 1935, who have collaborated on many projects over the past 40 years, and have been happily married for even longer. If you believed in astrology, you would probably say it was written in the stars.

But what does that say about people who, despite sharing a birthday, might have been born years apart? Perhaps nothing. All we can say is that your birthday should be of great significance to you. When it happens, enjoy yourself - but make sure that nobody sings you the song "Happy Birthday to You", because it's covered by copyright until 2030. (As the most frequently-sung song in the world, it rakes in $US2 million in royalties each year - even though most people who sing it don't actually pay anything.)

Above all, see your birthday as something positive. It doesn’t mean you’re getting older; it just means you’re getting presents.

Noivedya Juddery Canberra - Australia

Artistry In The Sand From Tiny Crabs

by Sharani RobinsA universe of natural wonder beckons from all corners of the globe. If I step through the doorway of awe and attention, nothing less than magic awaits whatever the address. Equipped with the naturalist's and explorer's perspective, God's natural creation sings a symphony of majesty.

I ventured out the other day onto the ocean beach, here in Malaysia, for a stroll carrying the odd combination of a script to memorize my lines for an upcoming performance and my camera in case adventure paid me a visit. While I tried to immerse myself in the character, the sand quickly diverted my attention while it shifted as if alive under my feet. Little holes popped up all over like little blowholes on a whale. In the blink of an eye, tiny crabs the same colour of the sand scurried about and disappeared down into the sand or appeared up from beneath the sand.

The sand was also formed into a vast mosaic of mandala shapes that appeared to be like bursts of fireworks exploding on the sand. Some places had tiny mounds that were perfectly formed spirals. Sooner than at once, my script had turned into a knee rest to protect my freshly laundered pants. It was all I could do to keep myself from lying down completely to watch the crabs with complete fascination so that I could better understand their world.

Mostly they disappear under the sand as soon as you come close to them. Actually observing them took some degree of patience and quiet. As I left the world of people aside, I finally began to understand that these crabs would create a little hole by carrying drops of wet sand up and out of the hole and then place the sand carefully around them, first creating their own version of a sandcastle with walls for their little hole. Sometimes as soon as they noticed me looking at them or trying to take a photo they disappeared back into the hole. Somehow I must have eventually adjusted myself more to their wavelength because as time passed and I moved slowly along the beach, I had better and better luck co-existing near them without them scurrying away.

I was rather overcome with awe as I realized that this vast network of spiral designs painted on the sand was the handiwork of tinier than the tiniest crabs (most of the ones I saw were no bigger than my fingernail). These designs in the sand looked just like mandalas created by a human artist. I tried to capture their artistry with my camera but I must confess that the pictures I will put in my online gallery album might not do them justice.

As I made my way back towards the hotel, in the distance I saw a large blue kite being flown in the sky on the beach. My intention was to capture a photo of it from a closer view but I kept stopping, setting my camera to close-up view and kneeling back down in the sand mesmerized by the tiny crabs. They so completely captivated my attention that by the time I got back to the hotel the kite flyer was long gone.

Did you ever know that sand crabs are artists adept at creating great masterpieces? I am continually amazed at the diversity and grandeur of Nature. It matters not whether I am a mere short distance from my house observing swans and ducks or thousands of miles away walking on a beach instead of a bike path. The common denominator seems to be that one step through the doorway of awe offers a sweeping journey into the domain of beauty. And I find adopting the viewpoint of a naturalist brings the deepest peace and satisfaction imaginable. It truly is a meditation for me. Finding divinity in the smallest aspects of God's creation only enhances its glory. Gratitude blossoms inside me every time I am so lucky to walk through that doorway of awe, which can be visited in every clime. I can only wish that someday you would also be lucky enough to discover the crab artists busy at work turning a sandy beach into a masterpiece.

Sharani Robins Rhode Island - USA

At The Beach

by Jogyata DallasPoor readers, we inflict upon you such long and tedious manuscripts - and it’s not as though we have anything really profound to say. I’m guilty, too, and you shall be forgiven if you skip past this very unrehearsed piece for a more thoughtful contributor. I’m only going to write something one sentence long – honestly, only one sentence. I promise.

If you lie on your back on the beach at Whangamata on one of these clear autumn nights, the stars up there in the black sky are so thick and mesmerizingly beautiful that you can only stare and stare in the silence of your wonder – before the moon comes up, the huge panorama of the cosmos is spread out in all its breathtaking glory, and you lie spread-eagled in the darkness with the warmth of the afternoon sun still rising from the yellow sand, and the heavens are alive with shooting stars and pulsing with lights from far off galaxies and the Milky Way is a great band of white, a long milky cloud stretching across the universe made up of countless unknowable worlds and I, sitting in my small room rummaging through these impressions and memories and marvelling at the beauty of this world, I remember too that afternoon before nightfall sitting in a red kayak one kilometer off-shore and looking back at the far-off, Lilliputian rows of weekend cottages in the village of Whangamata, framed in its mountainscape of green hills, and feeling the sea beneath me moving up and down slowly as though breathing, the living cadences of tide lifting me slowly up, slowly down, heaving vertical metres of the sea’s sighing, ever so gentle yet perilous beneath and if you tumble out here, alone and flapping your panicked arms in this frigid ocean, chilling to the marrow, you’re heaven-bent boyo, but you battle back through white caps and rising seas and ride a good last wave ashore like a conquering god, whooping with glee, keel grating onto the golden shells and you drag your skiff up into the dunes and now it’s midnights inky-dark except for those riotous stars and the lights of the nearby village are all out, everyone dreaming in their soft beds while above their closed eyes whole galaxies wheel and turn across indigo meadows of sky and you lie in your solitude of darkness filled with a desireless contentment, cradled by the earth like a child curled up, embraced beneath by the warm sand yielding to the hard edges of your bones and flesh, eyes closed in your calm and you sink into a meditative reverie reaching out with tendrils of feeling and consciousness to some hoped for understanding of everything, everything, curled and warmed in the yellow sand, no thoughts, no masks, no words, no self, awareness stretching out into infinity and everything of feeling distilled into a slow smile that moves across your face and you can almost feel the love and sadness of God, His patience and vastness spread out across this universe all around you and felt too in the solemn matrix of silence out of which all sounds and forms emerge and return, you a tiny atom of fragile flesh riding this sad earth planet on its peregrinations around the sun, whizzing across the black void of eternity, a brief spark of consciousness on a high velocity joy ride among the garrisons of stars, a speck of dust in the measureless storm cloud of the universe, then you wake from these musings to feel a sudden night breeze off the sea, soft as butterflies on your skin,

fragrant with seabed flotsam dumped in the last tide – seaweed, kelp, the exoskeletons of pincer crabs and dead fish – and your heart fills with images from long ago, yes the long ago summers of childhood, wandering dunes and coastlines, kneeling over rock pools stranded by falling tides, face immersed in the salty wet and peering into wondrous grottos filled with starfish, the severed orange claws of lobsters, pale sea lettuce, grey crabs scuttling beneath dark and sinister overhangs, spiny things and gorgeous luminescent shells attainable if you only dare to reach all the way down with your child’s hand into those scary water worlds where rows of sharp teeth and watchful predatory eyes lie waiting in silent concealment and my long ago parents were there with me then, my father’s face sometimes reassuringly against mine, plunged into the pool, his eyes magnified and round and laughing underwater at me, his big knuckles grabbing treasures fearlessly from the dark pools, but now gone out somewhere into the measureless conundrum of the universe, puzzling worlds of stars, gone to meet his Maker so my uncle said, returned into spirit and God-oneness – where we’ll all go eventually because we always were, are, will be, players in His funny-sad, bittersweet, cosmic dance-game, each of us playing the starring role in our own private tragi-comedies, wandering like these brilliant, aimless stars throughout eternity, you, me, all of us belonging among the multifarious, multitudinous characters in His great big amusement park universe where, equipped with an essential sense of humour you can enjoy these few moments as your human life few laps around the sun whizz by, a frolicsome romp, learning to grasp that only God is real, everything else an imagining in the mind, and seeing the futility of all striving, pomp and triumph; the vainglory of all action and ambition and thought; the emptiness of all phenomenal existence; the non-existence of an ego ‘I’; the rapturousness of closeness to God, yes, and the final legacy at the end of all our tears and smiles of knowing and understanding that everything that you searched for, in every person, place, thing, and everything you hoped and yearned for in the great solitude of your painful exile from God can only be found in union with Him and as you fall asleep, tired from all the sea air and still with sand in your toes, you’re saying under your sleepy breath, yes, God, do come, do come, do come.

Jogyata Dallas Auckland - New Zealand

Here's me playing with a ball, and my mum – a while ago now.

Here's me playing with a ball, and my mum – a while ago now.Be In Bremen Tomorrow At 3pm

by Kamalika GyörgyjakabI got the flower in Freiburg. It was a pristine and very persistent sunflower, it held its head high up even after travelling under all possible circumstances for seven consecutive days. Somebody said that sunflowers drop their heads quite shortly after being cut from their stem, but this one seemed to ignore the usual destiny of its kind. All in all, it was a very special sunflower and it magnificently tolerated all the hassle of car rides between Heidelberg and Nürnberg, tram rides in Mannheim, bus rides between Dachau and Dresden, traffic jams and bottlenecks around Dortmund... Now, after having seen Berlin, it was with me in Hamburg and it started to fade. 'That is the fate of flowers', I thought. One thing was sure though: I could not have just thrown this flower away. It was too special, it meant too much to me.

I didn’t have much time to ponder over the issue of perpetuating my sunflower. Our program in Hamburg was quite a rush and on top of that we got lost in a suburb of this huge settlement, so it was quite late in the night that I took farewell from my beloved ones and returned to our tiny hotel room. There a strange desire invaded me quite suddenly. 'Tomorrow I want to go to Bremen.'

I checked the maps and it seemed quite feasible, but this idea of mine was not really welcome. I was turning Claire’s program upside down. She was supposed to give me a ride from Hannover to Luxembourg and I was supposed to meet her in Hannover at a certain time next day. But I was dying to go to Bremen! She was nice enough to re-adjust her and her father’s program to my brand-new whim with a sigh.

I happened to share the room with Saskia. Upon telling her about the inexplicable impulse I felt about going to Bremen, she remarked without the slightest enthusiasm 'I was born in Bremen. I even studied there. I just don’t know how I ever lived there, it’s such a small and insignificant place.' This sounded anything but convincing, but it definitely couldn’t alter the plan. There was too strong child somewhere deep inside me and this kid was loudly protesting against all ideas that didn’t involve Bremen for next day. Fait accompli! After a copious breakfast I grabbed my bag, my increasingly ageing flower and I was off for a safe, glacierless, snowless adventure. A couple of hours in a train and I was placing my feet one before another in Bremen. And I was probably beaming with happiness without knowing what on earth was so special about my coming here.

I couldn’t decide whether its streets were familiar or I just imagined having already walked them in another century. I couldn’t decide whether it was the childhood tale of the famous musicians from Bremen that had planted a seed of curiosity and joy in me. I couldn’t decide what I exactly I wanted to do or see here. I just set off and walked merrily. Well before I reached the old town with its huge church (may I call it a cathedral?) and pretty streets, market squares and the renowned Musicians, I found a stream of water and an island-like place. Actually it was just a seemingly shallow and slow-flowing river that went around some city district and embellished a nice and big park with a well-kept windmill in its middle. I just KNEW that this was the place. The place where I had to be exactly then. It was a late September afternoon, but the number of flowery spots, flourishing bushes, blossoms obviously mocked at the calendar. My grandma taught me long ago not to sit down outside in the months that have an “r” in their names (including September). I giggled when this old memory turned up and I sat down quickly before I could obey tradition.

Being three o’clock in the afternoon I decided to meditate there for a few minutes. Every good Muslim finds a couple of minutes five times a day to spend with God. So, what is wrong with me? Let me give God a chance... Brownish-gold leaves were slowly floating away with the river. I was sitting in a kind of a peninsula under a sheltering shadow-donor tree, peace and poise incarnate. This quietest of all rivers came from my right, went around the peninsula and disappeared at my left.

Both I and the flower knew what was next. I touched it once more and then made just one single move. My sunflower was half a meter from the shore, slowly gaining distance from me. I still played with the thought of retrieving it. 'I could still reach it if I stretch a bit', then 'Oh, if I walked into the water I would still stand a chance of getting it back'... But I moved not. Only with the eyes did I follow the sunflower (that no longer was 'my' sunflower)... and felt what it could possibly feel: the touch of shiny cold water, the touch of the sun on the water, the slow but unceasing up and down movements and the pull of some mysterious force drifting it further and further towards the deeper parts, away from the banks and away from any fixed point that could attach it. While I kept my eyes mesmerised and fixed on this ever-diminishing tiny point in a slow but certain current of ever-new water, something happened.

There are moments that break the gridlines of time and run out wildly into the uncalculated and unmeasured freedom of nothing. Moments that cannot be captured, foreseen, grabbed by any watch, any wordsmith, any worldly idea. Moments when the shallow human sense incidentally falls into the coordinates of a giant astrologer and for a second it gets a glimpse of what one thousand billion years of light mean. These moments make one shiver when they bring the breeze of eternity closer to human concept. These moments make one absolutely certain that there is a God, and what’s more, He is tangibly right there, right then...

It was a moment like this. Through a veil powdered with little glittering diamonds – were they tears or miniature waves of this ever-moving fluid medium? – I could perceive an unknown and unknowable stream of love lingering between a little conscious point crouching on a riverbank and an even tinier sunflower vanishing in the distance. A nameless and data-less bliss grew out of this moment and enveloped the afternoon. The sunflower was perpetuated. So was the sacred corner of my conscience that recognised the play and the actors.

According to calendars and watches I spent approximately half of the September 22 afternoon in Bremen. According to the numberless Big Astrologic Book I was given a gargantuan portion of eternity, packed in some earthly seconds. And I came to realise that the previous evening’s almost hysteric yearning to come to Bremen was nothing else than a well-disguised telegraph from the Architect of unearthly time: 'Be in Bremen tomorrow at 3 p.m.' at the right time, at the right place. He only knows how he managed this in and through me, but I was there...

Kamalika Györgyjakab Hungary

I have always loved water. As a child, I would read every book on oceanography I could get my mother to buy me, and I would spend hours learning the names of the world’s oceans and of the myriad creatures that lived in them. It fascinated me, and still does, that so much of the ocean remains completely unexplored, and that the biodiversity in the ocean, although practically unknown, may far exceed anything on land.

I am professionally a waiter but by temperament I am a bookworm, a kitchen philosopher. For most of my life I’ve been able to achieve my goals on the strength of my intellectual tendencies. The American World Harmony Run changed all that. It forced me to use my body to challenge myself and my world at the same time. Here it wasn’t how well I could quote Sophocles that counted, but rather whether or not I could cover the ground with a spring in my step and a cheerful heart.

I just want to say that, after a long day of driving, cooking, packing and unpacking, getting lost and running on long open highways, nothing beats a leisurely swim, whether in a nice heated Jacuzzi that a hotel owner let us use, or just in a nameless lake in the middle of the New Mexico desert- as far away from the tourist traps as you can get.

Ironically, the World Harmony Run turned me into a swimmer. After I got back from the Run I joined a local YMCA and I now swim two or three times a week. If running clears the mind, then swimming relaxes and expands it. Sri Chinmoy noted that running and swimming both have something very special to offer on the spiritual plane, albeit in different ways.

Herman Melville once said something to the effect that if you took an absent-minded college professor into the wilderness, blindfolded him and spun him around three times, that he would immediately make his way to the nearest body of water, intuitively, if there were any water in the whole region. To quote him directly (from his delightfully rambling introduction to Moby Dick): “As everyone knows, meditation and water are wedded forever.”

Water teaches us to be adaptable, to accept life’s changes with grace and poise. On the World Harmony Run, I found myself always on the move. We never stayed in any location for more than a day. We were constantly talking to reporters, teachers, children, old folks and football and basketball players and basket weavers and quilters. The Run forced me to become as flexible as water, as gracious and accepting of other people as water accepts us all with its subtle and gracious touch.

On my last week of the run, I found myself in front of the mighty Pacific ocean. I had started the Run in St. Louis, Missouri, where the Mississippi river flows so languidly and yet so majestically. An east coast born and bred, nothing could have prepared me for the sheer beauty and power of the Pacific. I waded across the tidal flats and baptized myself with a few handfuls of the water. I am grateful to the World Harmony Run for the chance to discover new things about myself, and the inherent spirituality in Mother Nature.

Mahiruha Klein Philadelphia - USA

Bibliography

"Happy Birthday to Someone" by Mark JudderyMcCarty, Clifford. Bogey: The Films of Humphrey Bogart. New York: Citadel Press, 1965

Watson, Lyall. Supernature. New York: Anchor Press, 1973

White, Michael and John Gribbin. Darwin: A Life in Science. New York: Simon, 1995

"Economics - 'The Dismal Science'" - by Tejvan PettingerRuskin, John. Four Essays on the First Principles of Political Economy. London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1862 (Online Text at etext.virginia.edu)

Our members

Stories

First-hand experiences of meditation and spirituality.

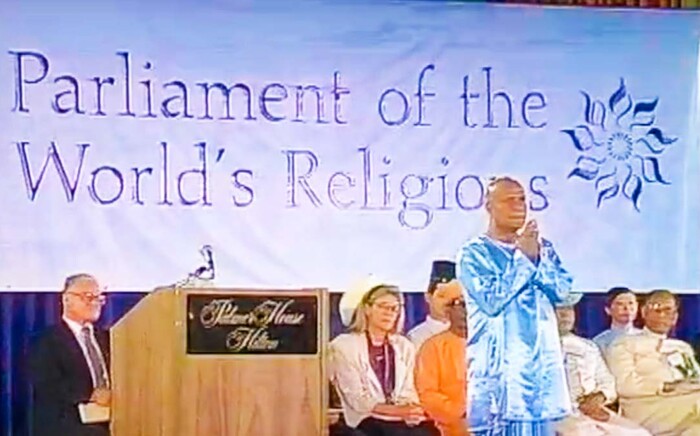

Sri Chinmoy's opening meditation at the Parliament of World Religions

Pradhan Balter Chicago, United States

The connection between Sri Chinmoy's music and my soul

Kamalakanta Nieves New York, United States

The first time that I really understood that I had a soul

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Filled with deepest joy

Tirtha Voelckner Munich, Germany

I felt a bell ringing in my heart

Charana Evans Cardiff, Wales

How my spiritual search led me to Sri Chinmoy

Vidura Groulx Montreal, Canada

Is it unspiritual to care about winning?

Tejvan Pettinger Oxford, United Kingdom

My first Guru

Adarini Inkei Geneva, Switzerland

'You two have been friends for many hundreds of years'

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

Why run 3100 miles?

Smarana Puntigam Vienna, Austria

My wife's soul comes to visit

Jogyata Dallas Auckland, New Zealand

The first time we met our Guru

Kaivalya, Devashishu and Sahadeva Torpy London, England

Breaking the world record for the longest game of hopscotch

Pipasa Glass & Jamini Young Seattle, United StatesSuggested videos

interviews with Sri Chinmoy's students

Self-transcendence in meditation

Kailash Beyer Zurich, Switzerland

What meditation gave me that I was missing

Purnahuti Wagner Guatemala City, Guatemala

Love, devotion and surrender

Pradhan Balter Chicago, United States

The greatest adventure that you can embark on

Mahatapa Palit New York, United States

A childhood meeting with Sri Chinmoy

Devashishu Torpy London, United Kingdom

From religion to spirituality

Muslim Badami Auckland, New Zealand

Selfless Service

Brian David Seattle, United States

Except where explicitly stated otherwise, the contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. read more »

SriChinmoyCentre.org is a Vasudeva Server project.